Effects of Maternal Choline Supplementation on the Septohippocampal Cholinergic System in the Ts65Dn Mouse Model of Down Syndrome

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2017 Jan 1.

Abstract

Down syndrome (DS), caused by trisomy of chromosome 21, is marked by intellectual disability (ID) and early onset of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathology including hippocampal cholinergic projection system degeneration. Here we determined the effects of age and maternal choline supplementation (MCS) on hippocampal cholinergic deficits in Ts65Dn mice. Ts65Dn mice and disomic (2N) littermates sacrificed at ages 6–8 and 14–18 mos were used for an aging study, and Ts65Dn and 2N mice derived from Ts65Dn dams were maintained on either a choline-supplemented or a choline-controlled diet (conception to weaning) and examined at 14–18 mos for MCS studies. In the latter, mice were behaviorally tested on the radial arm Morris water maze (RAWM) and hippocampal tissue was examined for intensity of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) immunoreactivity. Hippocampal ChAT activity was evaluated in a separate cohort. ChAT-positive fiber innervation was significantly higher in the hippocampus and dentate gyrus in Ts65Dn mice compared with 2N mice, independent of age or maternal diet. Similarly, hippocampal ChAT activity was significantly elevated in TS65Dn mice compared to 2N mice, independent of maternal diet. A significant increase with age was seen in hippocampal cholinergic innervation of 2N mice, but not Ts65Dn mice. Degree of ChAT intensity correlated negatively with spatial memory ability in unsupplemented 2N and Ts65Dn mice, but positively in MCS 2N mice. The increased innervation produced by MCS appears to improve hippocampal function, making this a therapy that may be exploited for future translational approaches in human DS.

Keywords: aging, cholinergic, Down syndrome, hippocampus, intellectual disability, maternal choline supplementation, spatial memory, Ts65Dn mice

1. INTRODUCTION

Down syndrome (DS) is a multi-faceted condition caused by triplication of human chromosome 21 (HSA21) that can result in defective function within cardiac, respiratory, endocrine, gastrointestinal, immunological, and central nervous systems; in addition, DS presents as cognitive problems in the domains of learning, language, and memory, forming an overall pervasive intellectual disability (ID) [1,2]. A premature aging phenotype is also observed that includes classic neuropathologic features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD): amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neuron (BFCN) systems [3,4]. BFCNs provide the major cholinergic innervation to the entire cortical mantle and the hippocampus [5,6], and dysfunction in this system results in significant cognitive difficulties. It is estimated that individuals with DS show a clinical presentation of dementia in ~50 % of cases over the age of fifty [7–11], although this may be an underestimation, as assessing cognitive decline in persons with ID is difficult and sometimes equivocal.

In both AD and DS, there is a decrease in cell size and density of BFCNs, culminating in a reduction in cholinergic innervation within the hippocampus [12–19]. There have been several attempts to mimic a DS-like phenotype in animal and cellular models. Although initial attempts with full trisomy models were not successful, segmental trisomic models of DS have proven to be extremely useful for DS and AD research. Specifically, key aspects of DS neuropathology, is recapitulated in the Ts65Dn mouse, making it a valuable translational model of DS and AD [20–27]. Ts65Dn mice are trisomic for a segmental region of murine chromosome 16 (MMU16) orthologous to part of human chromosome 21 (HSA21) [28–30]. For example, age-related alterations in the BFCN system of Ts65Dn mice have been reported for the septohippocampal cholinergic projection system, including neuronal loss [20,26,31,32], altered patterns of cholinergic innervation within cholinoceptive regions, and changes in activity levels of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), acetylcholinesterase (AChE), and high-affinity choline uptake (HACU) [33–36].

Recently, our group reported the effect of dietary maternal choline supplementation (MCS) on hippocampal-dependent behavior and BFCNs in adult (13–17 mos) Ts65Dn mice and 2N offspring [37]. Spatial mapping was impaired in unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice relative to 2N littermates, a significantly lower number and density of cholinergic neurons within the medial septal (MS) and vertical limb of the diagonal band (VDB) complex was seen in unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice compared with treatment-matched 2N mice, and MCS improved spatial learning and increased number and size of cholinergic MS and VDB neurons in Ts65Dn offspring [37]. The density and number of cholinergic MS neurons also correlated with spatial memory proficiency in adult Ts65Dn mice [37].

While many of the triplicated genes in human DS and the Ts65Dn mouse model are implicated in ID and age-related BFCN pathology, no specific metabolic pathway or process has been definitively shown to be responsible for the premature aging pathology observed in DS humans or trisomic murine models. This has made it difficult to develop an effective treatment strategy for the ID and early onset AD-like pathology of DS. A potential treatment approach involves maternal dietary supplementation with choline, an essential nutrient involved in neural tube closure, organogenesis, central nervous system cell membrane synthesis, and methylation-dependent gene expression [36,38–44]. MCS has both immediate and long-term beneficial effects in healthy disomic rats and mice [44–57], and in rodent models of prenatal ethanol exposure, Rett syndrome, and status epilepticus [58–63]. To explore the effects of early choline supplementation on cholinergic innervation and activity in the hippocampus of the adult brain, we used a MCS paradigm and studied adult male Ts65Dn and 2N offspring. Since cholinergic MS/VDB neurons innervate the hippocampus [5,6,64,65], it is likely that disruption of this memory circuit underlies some of the pervasive cognitive deficits seen in DS as well as age-related cognitive decline. While several independent groups have reported atrophic changes in Ts65Dn mice beginning as early as 2 mos of age, including decreased BFCN size, endosomal abnormalities, and defective retrograde transport, overall BFCN loss and decreased hippocampal cholinergic innervation is not seen consistently until after 10 mos [20–26]. In the present study, we determined the effects of MCS, provided via dietary supplementation from conception to weaning, upon septohippocampal cholinergic innervation and activity in adult Ts65Dn and 2N offspring.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

2.1.1. Aging Cohort

Male Ts65Dn and 2N mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) at 1 mo and 10 mos of age. Both genotypes are derived from a cross of female Ts65Dn and male C57BL/6JEiJ×B6EiC3SnF1/J mice, and only mice that were not homozygous for Pde6brd1, a gene that causes retinal deterioration and blindness, were used [26,66]. Final group numbers were: thirteen 2N and ten Ts65Dn mice between 6.5–8.1 mos of age, and thirteen 2N and eleven Ts65Dn mice between 13.9–18.4 mos of age (see Table 1). Groups of young-middle aged adult mice are referred to as 6–8-month-old mice and the two late middle-aged as 14–18-month-old mice.

Table 1.

Animal groups

| Aging Cohort | na | Age range (mean) |

|---|---|---|

| Young-adult mice (6–8 mos) | ||

| 2N | 13 | 6.5–8.0 (7.7) mos |

| Ts65Dn | 10 | 6.5–8.1 (7.5) mos |

| Late middle-aged mice (14–18 mos) | ||

| 2N | 13 | 14.0–17.9 (16.4) mos |

| Ts65Dn | 11 | 13.9–18.4 (16.3) mos |

|

| ||

| Hippocampal ChAT Intensity and Behavioral Analysis Cohort | na | Age range (mean) |

|

| ||

| 2N | ||

| Control diet | 11 | 13.7–17.8 (15.6) mos |

| Maternal choline-supplemented | 11 | 13.7–17.6 (15.4) mos |

| Ts65Dn | ||

| Control diet | 11 | 13.7–17.4 (15.9) mos |

| Maternal choline-supplemented | 11 | 13.8–17.6 (15.4) mos |

|

| ||

| Hippocampal ChAT Activity Cohort | na | Age range (mean) |

|

| ||

| 2N | ||

| Control diet | 15 | 14.7–17.3 (16.3) mos |

| Maternal choline-supplemented | 18 | 15.7–18.4 (16.8) mos |

| Ts65Dn | ||

| Control diet | 15 | 15.2–17.9 (16.5) mos |

| Maternal choline-supplemented | 18 | 16.2–18.6 (17.3) mos |

2.1.2. Choline Supplementation Cohorts

For the choline supplementation study, additional breeder pairs (Ts65Dn female and C57Bl/6J Eicher × C3H/HeSnJ F1 male mice) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, and mated and housed at Cornell University (Ithaca, NY, USA). For genotyping, tail snips or ear punches were taken at weaning and sent to Jackson laboratories where genotype as well as determination of Pde6brd1 homozygosity was discovered by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

After weaning at postnatal day 21, male pups were group-housed; genotypes were mixed as animals were coded and researchers experimentally blind to the genotype until post-data analysis. Mice were maintained on an inverse light:dark cycle and 6–8 wk prior to termination mice were singly housed. Separate cohorts were used to determine changes in ChAT-positive hippocampal innervation (n=11, aged 13.7–17.8 mos) and ChAT activity levels (n= 15–18 mice, aged 14.7–18.6 mos; see Table 1). Behavioral data reported in this study was derived from the same cohort of male mice processed for immunohistochemistry.

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cornell University and conform to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Choline Supplementation

Dams were randomly assigned to either a choline-controlled rodent chow diet (AIN-93G with 1.1 g/kg choline chloride; Dyets Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA) or a rodent chow diet with choline supplementation (AIN-93G with 5.0 g/kg choline chloride; 5.0 g/kg; Dyets Inc.) as previously reported [37,67–69]. The choline-supplemented diet provided approximately 4.5 times the concentration of choline in the normal diet, within the range of dietary variation observed in the human population [70]. Administration of choline as an oral supplement or through consumption of foods high in choline moiety content, increases plasma and cerebral spinal fluid levels of choline [71–73]. Moreover, increases in plasma choline levels directly correlate with increases in brain choline and acetylcholine (ACh) levels [74,75]. The breeder pairs were provided ad libitum access to their assigned diet. Offspring remained with their original dams until weaning; and postweaning, male offspring were fed the control diet, once per diem with an amount determined by weight (to avoid obesity).

2.3. Tissue Preparation

Mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (85 mg/kg)/xylazine (13 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection, and perfused transcardially with 0.9 % saline (50 ml), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (50 ml) in phosphate buffer (PB; 0.1M; pH = 7.4) as previously described [67,68]. Ages at sacrifice are listed in Table 1. For stereological and ChAT luminosity measurements, brains were extracted from the calvaria, postfixed for 24 h in the same fixative, and placed in a 30% sucrose PB solution at 4 °C until sectioning. Brains were then cut at 40 μm thickness in the coronal plane on a sliding freezing microtome and stored at 4 °C in a cryoprotectant solution (30 % ethylene glycol, 30 % glycerol, in 0.1 M PB). For ChAT enzymatic assay, mice were transcardially perfused with a 0.9 % saline solution, brains extracted, hippocampus dissected out on wet ice, and stored at −80° C until analysis.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously [76]. Briefly, a full series of sections from each animal was immunolabeled with a goat polyclonal antibody for choline acetyltransferase (ChAT; 1:1000 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), the non-rate-limiting enzyme for acetylcholine synthesis and a specific marker for cholinergic neurons [77]. Tissue was washed in phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.2, 1X) to remove excess cryoprotectant, rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.4, 1X), and incubated in sodium metaperiodate to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. Tissue was then washed in TBS containing 0.25 % Triton X-100 to enhance primary antibody penetrance. This was followed by 1 h incubation in a blocking solution consisting of 3% horse serum in TBS/Triton X-100, then incubation overnight at room temperature with the ChAT primary antibody in a solution of TBS/Triton X-100 with 1 % horse serum. All washes and incubations were carried out at room temperature on a shaker table.

Following overnight incubation, sections were washed in TBS and incubated for 1 h with a biotinylated secondary antibody (anti-goat IgG, host horse, 1:200, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), allowing for signal amplification by a proceeding incubation for 1 h in avidin-biotin-complex solution (Elite kit, Vector Laboratories, Inc.). Prior to chromogen reaction, tissue was washed in a sodium imidazole acetate buffer (0.68 g imidazole, 6.8 g sodium acetate trihydrate per 1 L distilled water, pH 7.4 with glacial acetic acid). Antibody immunolabeling was visualized with 0.05 % 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochochloride (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with 1 % nickel (II) ammonium sulfate hexahydrate and 0.0015 % H2O2. The reaction was terminated using fresh imidazole-acetate buffer solution, and sections were rinsed in PB, mounted on chrome-alum-gelatin-subbed slides, dried overnight at room temperature, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, cleared in xylenes, and cover-slipped with distyrene/dibutylphthalate (plasticizer)/xylene (DPX) mounting medium. Immunolabeling and mounting of sections was performed in one set, with animals randomized across baskets to reduce batch-to-batch variation, preclude group staining variation, and reduce overall experimental variance. Immunohistochemical controls with the omission of primary antibodies were conducted on tissue processed at the same time as the ChAT-immunolabeled sections. All procedures were performed blind to genotype and treatment.

2.5. ChAT Hippocampal Luminosity Measurements

The intensity of ChAT-immunolabeling was determined by tracing the hippocampus and dentate gyrus unilaterally at three points along its rostrocaudal axis using an X1 lens (n.a. 0.04). Photomicrographs were then taken with an X10 lens (n.a. 0.45) and montaged using Virtual Slice software (Stereo Investigator, MicroBrightField, Inc.) with re-focusing at every three sites [67]. For this procedure, all photomicrographs were taken at the same level of illumination, and a background image taken from a blank area of the glass slide was used to correct for alterations in luminosity across the plane of focus.

Intensity of ChAT-immunoreactive fibers was measured at 23 sites using ImageJ software (1.45s, 1.6.0–20, 32-bit) [78] including nine sites in the dentate gyrus (DG), eleven sites across the hippocampus proper, and three background sites within the corpus callosum white matter dorsal to the hippocampus. There were no differences between corpus callosum background measures for any groups or sections, all within < 1 % of each other average (0.96 %, or 2.45 units on a scale of 0–255). The three background measurements were averaged per section, and each hippocampal ChAT intensity measurement was divided by the average background measurement for that section. Because no difference was seen between the ventral and dorsal blades of the dentate gyrus, the data were pooled; for example, DG inner molecular layer (IML) intensity was calculated by averaging dorsal and ventral inner molecular layer values, and DG outer molecular layer (OML) intensity was calculated by averaging dorsal and ventral outer molecular layer values. Averaging all measurements across the DG and hippocampus proper derived total hippocampal ChAT intensity. Hippocampus proper intensity was determined by averaging CA2/3, CA1/2, and CA1 measurements. All calculations were performed for each subject, prior to calculating group values. Data are plotted as inverse values with 1.0 representing saturation with white light (pixel value 255) and values > 1.0 representative of increased ChAT intensity (pixel values < 255).

2.6. ChAT Radioenzymatic Assay

Hippocampus from Ts65Dn mice and age-matched 2N littermates at 14–18 mos (see Table 1) were processed for determination of ChAT enzyme activity using a modification of the Fonnum method [79–81]. Although the Fromun assay is a standard in the field for ChAT activity, the procedure has limitations and may detect carnitine acetyltransferase (CrAT) activity [82]. Frozen tissue from hippocampal dissections was homogenized using high frequency sonication in a solution containing 0.5 % Triton X-100 and 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Briefly, 5 μl of tissue homogenate was combined with C-14 labeled acetyl Co-A (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA, USA), incubation buffer (100 mM sodium phosphate, 600 mM NaCl, 20 mM choline chloride, 10 mM disodium EDTA, pH7.4), and physostigmine (20 mM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After 30 min of incubation at 37° C in a water bath, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 4 ml of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Subsequently, 1.6 ml of acetonitrile/tetrephenalboron mixture and 8 ml of scintillation fluid were added to cause phase separation. After the samples stabilized for 24 h, they were counted in a scintillation counter. Protein content of the samples was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). ChAT activity was expressed as μmol/h/g protein. Samples were coded, and all assays performed in triplicate by a technician blinded to genotype and treatment groups.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For hippocampal ChAT intensity analysis, the nonparametric Mann Whitney U test was used for determining differences between groups, and the Friedman test was used for within group comparisons; as such, all averages are presented as median. Statistics were conducted using Excel (14.0.6129.5000, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS (PASW Statistics 18, release 18.0.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). For hippocampal ChAT radioenzymatic data analysis, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

For behavioral analysis performed in a separate study [37], the 15 sessions were divided into 5 3-day blocks with mean number of errors committed per trial, averaged across blocks, established as the dependent measure. Nonparametric correlations were calculated using the Statistical Analysis System (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and are presented as Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs). The alpha level was set at 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Hippocampal Cholinergic Intensity in Ts65Dn and 2N Mice During Aging

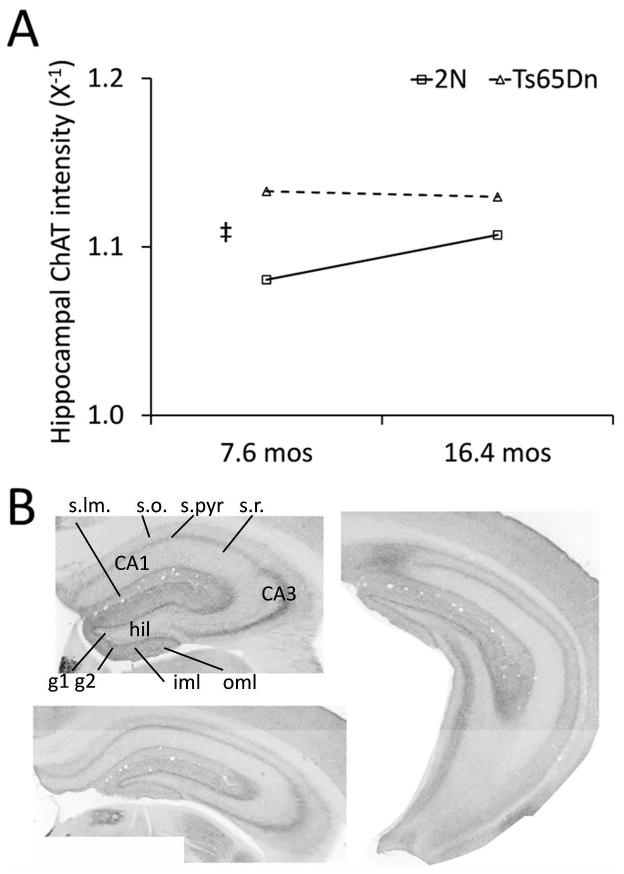

Examination of average ChAT intensity across the hippocampus and dentate gyrus was significantly increased by 65 % in Ts65Dn mice compared with 2N mice at 6–8 mos (p < 0.001, Figure 1). A significant 33 % age-related increase was seen in 2N mice at 14–18 mos compared with 2N mice at 6–8 mos (p < 0.05). No parallel change in ChAT intensity with age was observed in Ts65Dn mice, although a nonsignificant 21% increase in ChAT immunostaining was observed within Ts65Dn mice compared with 2N mice at 14–18 mos (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average ChAT intensity in the hippocampus and dentate gyrus of male Ts65Dn and 2N mice at 6–8 and 14–18 mos.

(A) Ts65Dn mice had overall higher levels of cholinergic innervation than 2N mice, as measured by ChAT-immunolabeling intensity, and 2N mice showed a significant increase with age (* p < 0.05, ‡ p < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U, two-tail, n = 10–13) Values are plotted as reciprocal (x−1) of luminosity and were derived by averaging measurements in all laminae and across the three sections along the rostrocaudal access used for evaluation, shown in B. Data presented represent medians for group.

ChAT intensity within individual hippocampal laminae showed elevated levels in Ts65Dn mice at 6–8 mos compared with age-matched 2N mice. These findings were largely driven by increased ChAT immunoreactivity within the rostral and middle sections across each hippocampal laminae examined (Table 2). In contrast, an age-related increase in a total ChAT intensity was seen in 2N mice, which was driven primarily by ChAT intensity in the stratum pyramidale in the rostral CA1–CA3 regions and by the granule and molecular layers of the dentate gyrus (Table 2).

Table 2.

ChAT intensity in the hippocampus proper and dentate gyrus across aging

| Hippocampus proper

|

Dentate gyrus

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA3/2

|

CA1

|

||||||||

| s.o. | s.pyr. | s.rad. | s.o. | s.pyr. | s.rad. | gran. | iml | oml | |

| Rostral | |||||||||

| 2N 6–8 mos | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ts65Dn 6–8 mos | 1.05* | 1.08* | 1.05 | 1.04* | 1.06* | 1.04 | 1.04** | 1.08** | 1.06** |

| 2N 14–18 mos | 1.05** | 1.09** | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.04* | 1.02 | 1.04* | 1.06* | 1.06* |

| Ts65Dn 14–18 mos | 1.06 | 1.10 | 1.04 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.10 |

|

| |||||||||

| Middle | |||||||||

| 2N 6–8 mos | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ts65Dn 6–8 mos | 1.04** | 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.08* | 1.04 | 1.05** | 1.10** | 1.08** |

| 2N 14–18 mos | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 1.03* | 1.04* |

| Ts65Dn 14–18 mos | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

|

| |||||||||

| Caudal | |||||||||

| 2N 6–8 mos | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ts65Dn 6–8 mos | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.04** | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.02 |

| 2N 14–18 mos | 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 |

| Ts65Dn 14–18 mos | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.06 |

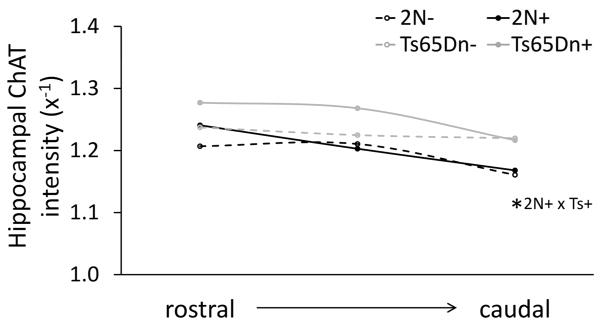

3.2. Elevated ChAT Intensity in the Hippocampus and Dentate Gyrus of Adult Ts65Dn Mice Independent of Maternal Diet

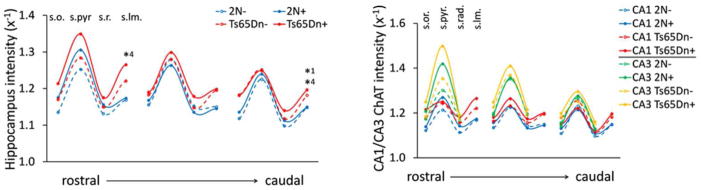

Similar to the aging cohort, when averaged across all laminae and subregions of the hippocampus and DG, ChAT intensity was consistently higher, on average by 19%, in unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice compared with unsupplemented 2N mice at 14–18 mos (see Table 1 and Figure 3). Mice exposed to MCS displayed a nonsignificant average 18 % increase in ChAT intensity in the rostral and middle aspects of the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice over genotype-matched unsupplemented mice; while, no change was observed within the rostral, middle, or caudal hippocampus of 2N mice exposed to MCS. In MCS offspring, ChAT intensity remained elevated in Ts65Dn mice over treatment-matched 2N mice, with a significantly higher level found in the caudal hippocampus (p < 0.05, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cholinergic innervation to the hippocampus proper laminae in MCS (+) and unsupplemented (−) male Ts65Dn mice and disomic littermates (2N) at 14–18 mos.

Line plots traversing the rostral through caudal hippocampus with measurements taken at laminae of the CA region were drawn using group medians for measurements at the stratum oriens (s.o.), stratum pyramidale (s.pyr), stratum radiatum (s.r.), and stratum lacunosum moleculare (s.lm.). (Left panel) Similar patterns of innervation were observed between groups in all hippocampal laminae (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; 1, 2N-compared with Ts65Dn−; 4, 2N+ compared with Ts65Dn+, Mann-Whitney U, two-tail, n = 11 per group). (Right panel) ChAT intensity was consistently higher in CA3 than CA1, (significance p < 0.05 or greater for all groups, not shown, Friedman test). All values plotted are reciprocal (x−1) values of luminosity measurements with light-microscope photomicrographs. CA1, cornu ammonis 1; CA3, cornu ammonis 3.

3.3. ChAT Intensity in the Hippocampus Proper

When individual laminae of the hippocampus were examined, patterns of innervation were comparable across the different hippocampal layers between Ts65Dn and 2N mice in both maternal diet conditions (Figure 3). For all groups, levels of ChAT intensity was highest in the stratum pyramidale (s.pyr.) and lowest in the stratum radiatum (s.r.) when CA1–CA3 regions were averaged. By contrast, ChAT intensity was higher in all laminae for CA3 compared to CA1 for all groups (Figure 3). Even in the s.pyr. layer of the rostral hippocampus where this effect was lowest in 2N and Ts65Dn unsupplemented mice, there was a significant difference between CA3 and CA1 (2N p < 0.001, Ts65Dn p < 0.01, Friedman test). MCS did not alter the pattern of innervation, but nonsignificantly increased the level of ChAT intensity in all CA1–CA3 laminae for both genotypes, markedly in the rostral hippocampus (Figure 3, Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of genotype and maternal choline supplementation on ChAT innervation in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn and 2N mice

| Genotype | Diet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 2N Control Diet vs Supp Diet | Ts65Dn Control Diet vs Supp Diet | Ts65Dn vs 2N Control Diet | Ts65Dn vs 2N Choline Supp Diet | |

| Rostral | ||||

| CA1 s.o. | —a | — | — | — |

| CA1 s.pyr. | — | — | — | — |

| CA1 s.rad. | — | — | — | — |

| CA s.l.m. | — | ↑4% | ↑4% | ↑8%* |

| CA3/2 s.o. | ↑4% | ↑4% | ↑3% | ↑3% |

| CA3/2 s.pyr. | ↑4% | ↑5% | ↑3% | — |

| CA3/2 s.rad. | — | — | — | — |

| DG granule | ↑4%* | ↑6% | ↑6% | ↑7%* |

| DG iml | — | ↑4% | ↑7%* | ↑5%** |

| DG oml | ↑4% | — | ↑8% | ↑5%* |

| Middle | ||||

| CA1 s.o. | — | — | — | — |

| CA1 s.pyr. | — | — | — | — |

| CA1 s.rad. | — | — | — | — |

| CA s.l.m. | — | — | ↑4% | ↑5% |

| CA3/2 s.o. | — | — | — | — |

| CA3/2 s.pyr. | — | — | — | ↑3% |

| CA3/2 s.rad. | — | ↑3% | — | ↑4% |

| DG granule | — | ↑8% | ↑3% | ↑14%* |

| DG iml | — | ↑3% | ↑8%** | ↑10%* |

| DG oml | — | — | ↑7% | ↑7%* |

| Caudal | ||||

| CA1 s.o. | — | — | — | — |

| CA1 s.pyr. | — | — | — | — |

| CA1 s.rad. | — | — | — | — |

| CA s.l.m. | — | — | ↑3%* | ↑4%* |

| CA3/2 s.o. | — | — | ↑6% | ↑5% |

| CA3/2 s.pyr. | — | — | — | ↑3% |

| CA3/2 s.rad. | — | — | — | — |

| DG granule | — | ↑3% | ↑5%* | ↑7%** |

| DG iml | — | — | ↑9%* | ↑8%** |

| DG oml | — | — | ↑9% | ↑8%* |

3.4. ChAT Intensity in the Dentate Gyrus

Higher levels of ChAT intensity were seen in Ts65Dn mice compared with treatment-matched 2N mice in granule, hilus, and molecular layers of the DG (significance shown in Figure 4, where 1 denotes significance between genotypes in unsupplemented mice and 4 in supplemented mice). A nonsignificant average 23 % increase in ChAT intensity was seen in the granule layer of Ts65Dn mice that received MCS, with little change observed in 2N offspring exposed to MCS (Figure 4). ChAT intensity was consistently elevated in the OML compared with the IML for all groups, with no effect of genotype or treatment observed (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Cholinergic innervation to the dentate gyrus in MCS (+) and unsupplemented (−) male Ts65Dn mice and disomic littermates (2N) at 14–18 mos.

Line plots depict median ChAT luminosity measurements from the rostral hippocampus through the caudal hippocampus, with measurements taken at the hilus (hil), granule layer low density (g1), granule layer high density (g2), and dentate gyrus inner molecular layer (iml) and outer molecular layer (oml). (Left panel) Laminae-dependent alterations to the dentate gyrus were observed with maternal choline supplementation (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; 1, 2N- compared with Ts65Dn−; 2, 2N- compared with 2N+, 4, 2N+ compared with Ts65Dn+, Mann-Whitney U, two-tail, n = 11 per group), and (Right panel) comparison of the inner molecular layer (IML) with the outer molecular layer (OML) shows consistently higher innervation to the OML for all groups (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, † p < 0.001, Friedman test, two-tail, n = 11 per group). All values plotted represent group medians and are reciprocal (x−1) values of luminosity measurements with light-microscope photomicrographs.

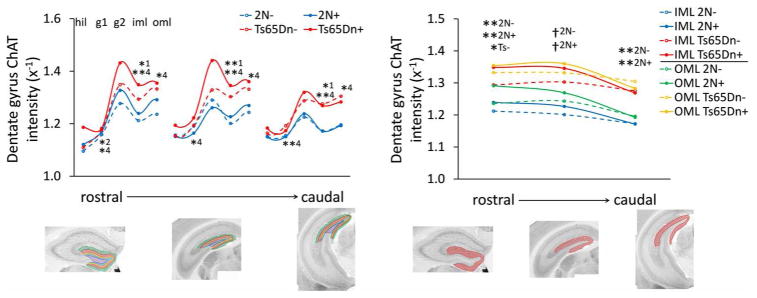

3.5. Examination of ChAT Intensity in the Dentate Gyrus Inner and Outer Molecular Layers

Similar to the hippocampus proper (Figure 3), Ts65Dn mice had significantly higher ChAT intensity values than maternal diet-matched 2N mice for the IML (rostral and caudal unsupplemented, p < 0.05; middle unsupplemented, p < 0.01; rostral, middle, and caudal supplemented, p < 0.01), and in supplemented groups for the OML (rostral, middle, and caudal, p < 0.05; Figure 5). However, no significant change with MCS was seen for offspring of either genotype (Figure 5, Table 3).

Figure 5. Cholinergic innervation to the molecular layers of the dentate gyrus in MCS (+) and unsupplemented (−) male Ts65Dn mice and disomic littermates (2N) at 14–18 mos.

Elevated ChAT intensity is seen in the inner molecular layer (IML) of Ts65Dn mice compared with 2N mice independent of treatment condition, but only in the outer molecular layer (OML) for groups that received MCS (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; Mann-Whitney U, two-tail, n = 11 per group). All values represent medians and are plotted as reciprocal (x−1) values of luminosity measurements derived using light-microscope photomicrographs.

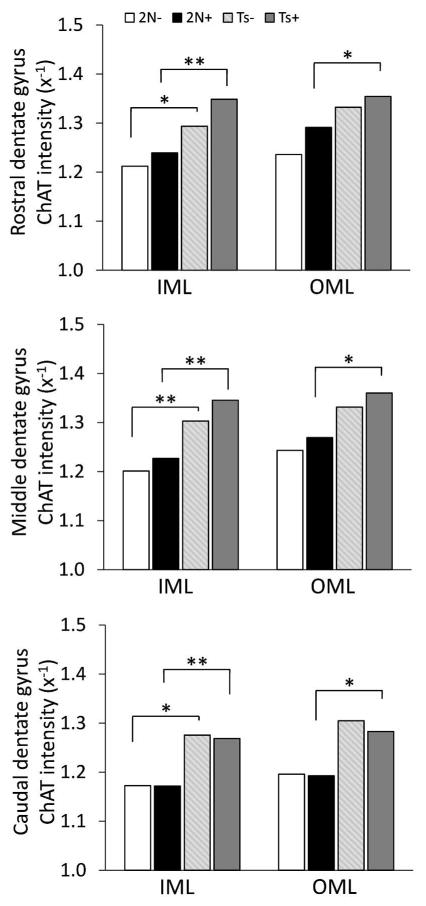

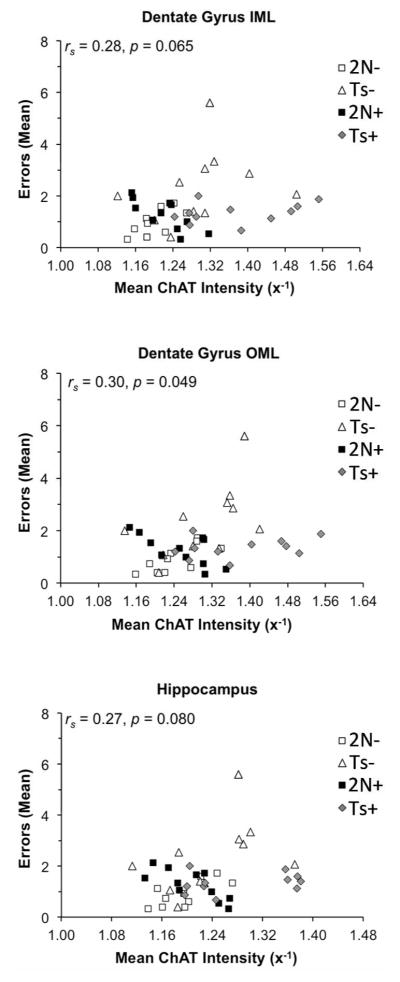

3.6. RAWM Performance and Hippocampal ChAT Intensity

Behavioral testing of the mice used in this study were correlated with the current morphometric findings. Positive associations between mean number of maze errors and the intensity of ChAT-immunolabeling were observed in the DG OML (rs= 0.30, p = 0.049; Figure 6), DG IML (rs= 0.28, p = 0.065; Figure 6), and the hippocampus proper (rs= 0.27, p = 0.080; Figure 6), indicating that greater ChAT intensity was associated with poorer spatial memory performance. However, this relationship was largely driven by unsupplemented groups where a significant positive relationship was seen between mean number of errors and ChAT intensity in the OML (rs= 0.83, p = 0.003) and IML (rs= 0.64, p = 0.044) of the DG, as well as the hippocampus proper (rs = 0.67, p = 0.034) of 2N unsupplemented mice (rs= 0.67, p = 0.035), and in the OML (rs = 0.67, p = 0.023) and IML (rs = 0.63, p = 0.039) of the DG, and the hippocampus proper (rs = 0.63, p = 0.038) of unsupplemented Ts65Dn mice. In contrast, supplemented 2N mice showed a negative correlation between mean number of errors and ChAT-positive intensity (OML, rs = −0.72, p = 0.013; IML, rs = −0.81, p = 0.003; hippocampus, rs = −0.76, p = 0.006; Figure 6), whereas supplemented Ts65Dn mice showed no correlation (OML, rs = 0.26, p = 0.43; IML, rs = 0.37, p = 0.25; hippocampus, rs = 0.27, p = 0.41; Figure 6).

Figure 6. Correlations between behavioral performance on the RAWM and ChAT intensity levels in the hippocampus.

Mean of errors in representative block 3 of the hidden platform task positively correlated with the intensity of ChAT immunolabeling in the inner molecular layer (IML) and outer molecular layer (OML) of the dentate gyrus as well as in the hippocampus proper for maternal choline supplemented (+) and unsupplemented (−) male Ts65Dn (Ts) mice and disomic (2N) littermates at 14–18 mos. rs, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

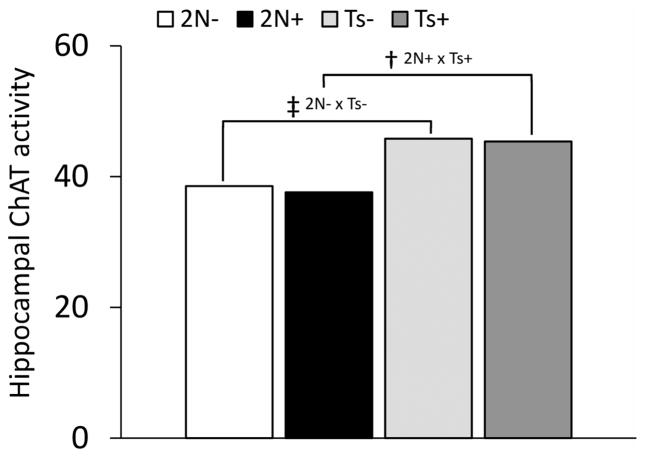

3.7. Elevated ChAT Activity in the Hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice

Quantitative biochemical analysis revealed elevated hippocampal ChAT activity in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice compared with 2N littermates at age 14–18 mos, independent of maternal diet (unsupplemented, p < 0.0001; choline supplemented, p < 0.005; Figure 7).

Figure 7. Hippocampal ChAT enzyme activity in MCS (+) and unsupplemented (−) male Ts65Dn mice and disomic littermates (2N) at 15–19 mos.

ChAT activity is elevated in the hippocampus of Ts65Dn mice compared with age-matched 2N mice, independent of maternal diet treatment group († p < 0.005, ‡ p < 0.001; Mann-Whitney U, two-tail, n = 15–18 per group). Values plotted are representative of group medians.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Aging

The present findings did not reveal elevated hippocampal ChAT intensity with age in Ts65Dn mice, while an age-related increase in total hippocampal ChAT intensity was observed in 2N littermates. This increase in a hippocampal cholinergic marker is similar to that seen in people with a clinical diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), an assumed prodromal stage of AD, prior to frank BFCN loss [83–87].

Ts65Dn mice are born with intact BFCNs in the MS, which provide cholinergic innervation to the hippocampus, and atrophy beginning at approximately 4–6 mos of age [24–26]. However, we did not find a decrease in hippocampal ChAT intensity between young and old Ts65Dn mice, suggesting that there is either an increase in ChAT protein production per neuron and/or an increase in cholinergic fiber branching, resulting in preserved elevated levels of ChAT intensity within the hippocampus throughout middle adulthood ages. It is possible that an increase in ChAT intensity with aging, similar to that found in 2N mice, is masked by age-related BFCN phenotypic degeneration in Ts65Dn mice.

4.2. Genotype Differences

In this study, immunohistochemical and biochemical analyses revealed a subregion-specific elevation of ChAT intensity within the hippocampus at 14–18 mos and an overall elevation of ChAT activity in unsupplemented Ts65Dn compared with unsupplemented 2N mice at 14–18 mos. Previous studies have reported similar higher levels of ChAT-positive fiber innervation and ChAT enzyme activity in the hippocampus and neocortex of Ts65Dn mice compared with 2N mice at 10–12 mos [20,21]. In previous studies, measurement of the activity of the ACh degrading enzyme AChE revealed an upregulation in the olfactory cortex but not in hippocampus in 10- and 19-month-old Ts65Dn mice [20]. Together with the present study, these findings suggest a disconnect within the hippocampal cholinergic biochemistry in the Ts65Dn mouse. Whether cholinergic biochemical function in the forebrain cholinergic system is hindered by increased ChAT fiber reorganization, or whether this increased innervation is indicative of biochemical and structural alterations remains unknown.

Although we observed genotype-dependent differences in levels of hippocampal ChAT intensity, no differences were found in the overall pattern of cholinergic innervation. Unlike neuron number, fiber branching is generally considered a dynamic, neuroplastic process. Neuronal processes fluctuate in accordance with a multitude of factors: diet, insult, disease, hormones, age, external experience, internal computation, and even circadian rhythms, among others [88–93]. The fact that we found elevations in both young [67] and older (present study) mice suggests a homeostatic drive upon forebrain cholinergic tone associated with the aneuploidic state.

In rodent dentate gyrus, spines are primarily located on the outer two-thirds of dendrites in the hippocampal molecular layer, a primary site for glutamatergic input [94]. Increased cholinergic innervation to the IML at the expense of innervation to the OML would likely disrupt excitatory input, interfering with spatial summation of glutamatergic input to the hippocampus. Since we did not find evidence that such remodeling occurs in Ts65Dn mice, it is likely that the behavioral decrements reported in prior studies result from other types of neuronal dysfunction [37]. Moreover, increased innervation alone may be indicative of dysfunction resulting in the inability to discriminate between task-relevant and task-irrelevant signals [64]. More work is needed to determine whether the differences reported here have direct behavioral correlates, or whether there are compensatory alterations at cholinoceptive sites that prevent detectable differences at the behavioral level.

4.3. Maternal Choline Supplementation

MCS increased ChAT intensity in the hippocampus and DG of adult Ts65Dn mice, similar to our previous findings showing an increase in hippocampal ChAT intensity in MCS Ts65Dn mice at 4–6 mos of age [67]. The consistent cholinergic elevation across the animal’s lifespan suggests that MCS produces an organizational upregulation of cholinergic innervation within the hippocampus beginning early in development. Although few previous studies have been conducted using prenatal choline-supplemented disomic rodents over 12 mos of age, a single study reported increased ACh evoked-release in the hippocampus of prenatal choline-supplemented aged rats (> 24 mos) compared to unsupplemented controls [95]. Due to choline’s known role in epigenetic remodeling [96,97], particularly within the cholinergic system [98], MCS may have a profound, lifelong cellular effect through methylation that is beneficial to the offspring independent of genotype [96–99].

4.4. Functional Consequences of Increased Hippocampal Cholinergic Innervation Associated with Aging, Genotype, and MCS

Correlational analyses provided insight into the functional consequences of increased hippocampal ChAT intensity seen with aging, trisomy, and MCS. A significant positive association was seen between number of maze errors and degree of ChAT intensity in the hippocampus of unsupplemented mice of both genotypes. Increased cholinergic tone may reflect an attempt to compensate for a progressively dysfunctional system, similar to what is observed in human prodromal AD where ChAT activity increases in the forebrain before ultimately decreasing as dementia progresses [83–87,99]. However, the association between poorer performance suggests a maladaptive compensatory response, similar to that reported following temporal lobe epilepsy [100,101].

In contrast, a strong negative correlation between number of maze errors and hippocampal ChAT intensity was seen in the supplemented 2N mice, demonstrating that increased ChAT immunoreactivity associated with MCS is beneficial depending on genotype. This suggests the MCS-related increased cholinergic tone observed in 2N mice is fundamentally different from that observed in Ts65Dn mice or during aging of 2N mice. No correlation between errors and ChAT intensity was found in the supplemented Ts65Dn mice; however, as these mice show elevated innervation throughout life, we might be observing a plateau for behavioral impact.

Understanding the specific mechanism(s) by which MCS exerts life-long effects on offspring hippocampal cholinergic innervation is an area of great interest. Organizational brain changes may result from choline’s role as the precursor to phosphatidylcholine, a major constituent of neuronal cellular membranes, and, to a lesser extent, as a precursor of ACh, which is a key ontogenetic signal during development [34,51,57,102]. Additionally, long-term effects of early choline supplementation may be related to epigenetic factors with lasting effects on gene expression, secondary to choline’s role as a methyl donor [39,103–105].

Despite a lack of understanding the mechanism(s) of action of MCS, several rodent studies have shown that supplementing the maternal diet with additional choline produces lifelong beneficial cognitive effects for offspring and reduces age-related cognitive decline [48,106,107]. MCS also ameliorates dysfunction in rodent models of human disorders including fetal alcohol syndrome, Rett syndrome, epilepsy, and schizophrenia [58,60,62,63,108]. Since nerve growth factor (NGF) is involved in the maintenance of BFCNs during development and in DS models of axonal transport whereby NGF is inhibited, it is important to consider interaction(s) between neurotrophic activity and choline supplementation as well as hippocampal neuroplasticity and behavioral responses in Ts65Dn and 2N mice [26,31]. The present findings suggest that increasing maternal choline intake during pregnancy provides, in part, some developmental and age-related protection towards the hippocampal cholinergic system dysfunction seen in DS

CONCLUSIONS

The findings reported here demonstrate that increased hippocampal ChAT immunoreactive intensity occurs with aging in 2N mice, while Ts65Dn mice have elevated innervation compared with 2N mice at multiple ages but do not show a significant aging effect. Interestingly, increased cholinergic tone correlated with poorer cognitive performance in Ts65Dn and 2N mice born to unsupplemented Ts65Dn dams, while an opposite pattern was seen in 2N mice that received MCS. The genotype-dependent differential mechanisms impacting behavior remain elusive, but we hypothesize that the changes reflect an attempt at neural reorganization, that may or may not be beneficial to the animal depending on genotype. Although increases in ChAT activity similar to those observed in the present study have been seen during the early phase of AD, these increases did not co-occur with structural changes in cholinergic fiber innervation [89], suggesting that the aging brain has the capacity to mount a neuroplastic biochemical response in the face of neurodegenerative insults. Such a response may be muted in a developmental disorder, such as DS.

Nonetheless, prior studies from our group have shown that enhancing the septohippocampal cholinergic system from an early age provides long-lasting benefit on the cognitive deficits observed in DS [37]. Our structure-function studies suggest that a simple dietary treatment approach such as early choline supplementation may prove a partial prophylaxis for cholinergic related deficits in AD of disomic and DS populations. Overall, MCS appears to be a promising treatment approach for neurodevelopmental disorders including DS.

Figure 2. Average ChAT-positive fiber innervation in the hippocampus of MCS (+) and unsupplemented (−) male Ts65Dn and 2N mice at 14–18 mos.

ChAT intensity averaged across all regions and laminae is shown as medians for each group and location. Ts65Dn supplemented mice had consistently higher values of ChAT intensity than 2N supplemented mice, significant in the caudal section (* p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U, two-tail, n = 11 for each group). Values are plotted as reciprocal (x−1) of luminosity measures.

Acknowledgments

We thank our collaborator Marie A. Caudill, Ph.D., for her support on our collaborative research. We thank Irina Elarova, M.S., Arthur Saltzman, M.S., and William Paljug for expert technical assistance.

FUNDING

Funding was provided by the NIH, HD057564 (BJS, EJM, SDG), HD45224 (MDI), PO1AG014449 (EJM, SDG), AG043375 (EJM & SDG), AG107617 (SDG); and the Alzheimer’s Association, IIRG-12-237253 (SDG).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Määttä T, Tervo-Määttä T, Taanila A, Kaski M, Iivanainen M. Mental health, behaviour and intellectual abilities of people with Down syndrome. Downs Syndr Res Pract. 2006;11(1):37–43. doi: 10.3104/reports.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein CJ. Epilogue: toward the twenty-first century with Down syndrome--a personal view of how far we have come and of how far we can reasonably expect to go. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;393:241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mufson EJ, Counts SE, Perez SE, Ginsberg SD. Cholinergic system during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease: therapeutic implications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(11):1703–18. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.11.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sendera TJ, Ma SY, Jaffar S, Kozlowski PB, Kordower JH, Mawal Y, et al. Reduction in TrkA-immunoreactive neurons is not associated with an overexpression of galaninergic fibers within the nucleus basalis in Down’s syndrome. J Neurochem. 2000;74(3):1185–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levey AI. Central cholinergic pathways in the rat: an overview based on an alternative nomenclature (Ch1–Ch6) Neuroscience. 1983;10(4):1185–201. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Wainer BH. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata): and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214(2):170–97. doi: 10.1002/cne.902140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wegiel J, Wisniewski HM, Dziewiatkowski J, Popovitch ER, Tarnawski M. Differential susceptibility to neurofibrillary pathology among patients with Down syndrome. Dementia. 1996;7(3):135–41. doi: 10.1159/000106868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hof PR, Bouras C, Perl DP, Sparks DL, Mehta N, Morrison JH. Age-related distribution of neuropathologic changes in the cerebral cortex of patients with Down’s syndrome. Quantitative regional analysis and comparison with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(4):379–91. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540280065020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisniewski KE, Dalton AJ, McLachlan C, Wen GY, Wisniewski HM. Alzheimer’s disease in Down’s syndrome: clinicopathologic studies. Neurology. 1985;35(7):957–61. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.7.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wisniewski KE, Wisniewski HM, Wen GY. Occurrence of neuropathological changes and dementia of Alzheimer’s disease in Down’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1985;17(3):278–82. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann DM, Yates PO, Marcyniuk B. Alzheimer’s presenile dementia, senile dementia of Alzheimer type and Down’s syndrome in middle age form an age related continuum of pathological changes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1984;10(3):185–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1984.tb00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jørgensen OS, Brooksbank BW, Balázs R. Neuronal plasticity and astrocytic reaction in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. J Neurol Sci. 1990;98(1):63–79. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90182-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mufson EJ, Bothwell M, Kordower JH. Loss of nerve growth factor receptor-containing neurons in Alzheimer’s disease: a quantitative analysis across subregions of the basal forebrain. Exp Neurol. 1989;105(3):221–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(89)90124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coyle JT, Oster-Granite ML, Reeves RH, Gearhart JD. Down syndrome, Alzheimer’s disease and the trisomy 16 mouse. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11(9):390–4. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casanova MF, Walker LC, Whitehouse PJ, Price DL. Abnormalities of the nucleus basalis in Down’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1985;18(3):310–3. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann DM, Yates PO, Marcyniuk B. Changes in nerve cells of the nucleus basalis of Meynert in Alzheimer’s disease and their relationship to ageing and to the accumulation of lipofuscin pigment. Mech Ageing Dev. 1984;25(1–2):189–204. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitehouse PJ, Struble RG, Hedreen JC, Clark AW, White CL, Parhad IM, et al. Neuroanatomical evidence for a cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1983;19(3):437–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yates CM, Simpson J, Gordon A, Maloney AF, Allison Y, Ritchie IM, et al. Catecholamines and cholinergic enzymes in pre-senile and senile Alzheimer-type dementia and Down’s syndrome. Brain Res. 1983;280(1):119–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yates CM, Simpson J, Maloney AF, Gordon A, Reid AH. Alzheimer-like cholinergic deficiency in Down syndrome. Lancet. 1980;2(8201):979. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contestabile A, Fila T, Bartesaghi R, Contestabile A, Ciani E. Choline acetyltransferase activity at different ages in brain of Ts65Dn mice, an animal model for Down’s syndrome and related neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurochem. 2006;97(2):515–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo H, Isacson O. Abnormal APP, cholinergic and cognitive function in Ts65Dn Down’s model mice. Exp Neurol. 2005;193(2):469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cataldo AM, Petanceska S, Peterhoff CM, Terio NB, Epstein CJ, Villar A, et al. App gene dosage modulates endosomal abnormalities of Alzheimer’s disease in a segmental trisomy 16 mouse model of down syndrome. J Neurosci. 2003;23(17):6788–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06788.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter CL, Isacson O, Nelson M, Bimonte-Nelson H, Seo H, Lin L, et al. Regional alterations in amyloid precursor protein and nerve growth factor across age in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome. Neurosci Res. 2003;45(4):437–45. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(03)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper JD, Salehi A, Delcroix JD, Howe CL, Belichenko PV, Chua-Couzens J, et al. Failed retrograde transport of NGF in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome: reversal of cholinergic neurodegenerative phenotypes following NGF infusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10439–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181219298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Granholm AC, Sanders LA, Crnic LS. Loss of cholinergic phenotype in basal forebrain coincides with cognitive decline in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome. Exp Neurol. 2000;161(2):647–63. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holtzman DM, Santucci D, Kilbridge J, Chua-Couzens J, Fontana DJ, Daniels SE, et al. Developmental abnormalities and age-related neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(23):13333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamlett E, Boger HA, Ledreux A, Kelley CM, Mufson EJ, Falangola MF, et al. Cognitive impairment, neuroimaging and Alzheimer neuropathology in mouse models of Down syndrome. CAR. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150921095505. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahlem P, Sultan M, Herwig R, Steinfath M, Balzereit D, Eppens B, et al. Transcript level alterations reflect gene dosage effects across multiple tissues in a mouse model of down syndrome. Genome Res. 2004;14(7):1258–67. doi: 10.1101/gr.1951304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akeson EC, Lambert JP, Narayanswami S, Gardiner K, Bechtel LJ, Davisson MT. Ts65Dn -- localization of the translocation breakpoint and trisomic gene content in a mouse model for Down syndrome. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;93(3–4):270–6. doi: 10.1159/000056997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeves RH, Irving NG, Moran TH, Wohn A, Kitt C, Sisodia SS, et al. A mouse model for Down syndrome exhibits learning and behaviour deficits. Nat Genet. 1995;11(2):177–84. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salehi A, Delcroix JD, Belichenko PV, Zhan K, Wu C, Valletta JS, et al. Increased App expression in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome disrupts NGF transport and causes cholinergic neuron degeneration. Neuron. 2006;51(1):29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter CL, Bachman D, Granholm AC. Minocycline prevents cholinergic loss in a mouse model of Down’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(5):675–88. doi: 10.1002/ana.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellott TJ, Kowall NW, Lopez-Coviella I, Blusztajn JK. Prenatal choline deficiency increases choline transporter expression in the septum and hippocampus during postnatal development and in adulthood in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1151:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK, Meck WH, Williams CL, Fitzgerald CM, Rosene DL, et al. Prenatal availability of choline alters the development of acetylcholinesterase in the rat hippocampus. Dev Neurosci. 1999;21(2):94–104. doi: 10.1159/000017371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cermak JM, Holler T, Jackson DA, Blusztajn JK. Prenatal availability of choline modifies development of the hippocampal cholinergic system. FASEB J. 1998;12(3):349–57. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blusztajn JK. Choline, a vital amine. Science. 1998;281(5378):794–5. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ash JA, Velazquez R, Kelley CM, Powers BE, Ginsberg SD, Mufson EJ, et al. Maternal choline supplementation improves spatial mapping and increases basal forebrain cholinergic neuron number and size in aged Ts65Dn mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;70:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wurtman RJ, Cansev M, Sakamoto T, Ulus IH. Administration of docosahexaenoic acid, uridine and choline increases levels of synaptic membranes and dendritic spines in rodent brain. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2009;99:71–96. doi: 10.1159/000192998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niculescu MD, Yamamuro Y, Zeisel SH. Choline availability modulates human neuroblastoma cell proliferation and alters the methylation of the promoter region of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 gene. J Neurochem. 2004;89(5):1252–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cooney CA, Dave AA, Wolff GL. Maternal methyl supplements in mice affect epigenetic variation and DNA methylation of offspring. J Nutr. 2002;132(8Suppl):2393S–400S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2393S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher MC, Zeisel SH, Mar MH, Sadler TW. Perturbations in choline metabolism cause neural tube defects in mouse embryos in vitro. FASEB J. 2002;16(6):619–21. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0564fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher MC, Zeisel SH, Mar MH, Sadler TW. Inhibitors of choline uptake and metabolism cause developmental abnormalities in neurulating mouse embryos. Teratology. 2001;64(2):114–22. doi: 10.1002/tera.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeisel SH. Choline: an essential nutrient for humans. Nutrition. 2000;16(7–8):669–71. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeisel SH, Blusztajn JK. Choline and human nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:269–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.14.070194.001413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Q, Guo-Ross S, Lewis DV, Turner D, White AM, Wilson WA, et al. Dietary prenatal choline supplementation alters postnatal hippocampal structure and function. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91(4):1545–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.00785.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mellott TJ, Williams CL, Meck WH, Blusztajn JK. Prenatal choline supplementation advances hippocampal development and enhances MAPK and CREB activation. FASEB J. 2004;18(3):545–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0877fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sandstrom NJ, Loy R, Williams CL. Prenatal choline supplementation increases NGF levels in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of young and adult rats. Brain Res. 2002;947(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meck WH, Williams CL. Metabolic imprinting of choline by its availability during gestation: implications for memory and attentional processing across the lifespan. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27(4):385–99. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meck WH, Williams CL. Choline supplementation during prenatal development reduces proactive interference in spatial memory. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;118(1–2):51–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meck WH, Williams CL. Characterization of the facilitative effects of perinatal choline supplementation on timing and temporal memory. Neuroreport. 1997;8(13):2831–5. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meck WH, Smith RA, Williams CL. Organizational changes in cholinergic activity and enhanced visuospatial memory as a function of choline administered prenatally or postnatally or both. Behav Neurosci. 1989;103(6):1234–41. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.6.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meck WH, Smith RA, Williams CL. Pre- and postnatal choline supplementation produces long-term facilitation of spatial memory. Dev Psychobiol. 1988;21(4):339–53. doi: 10.1002/dev.420210405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tees RC. The influences of rearing environment and neonatal choline dietary supplementation on spatial learning and memory in adult rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;105(2):173–88. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pyapali GK, Turner DA, Williams CL, Meck WH, Swartzwelder HS. Prenatal dietary choline supplementation decreases the threshold for induction of long-term potentiation in young adult rats. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79(4):1790–6. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Holler T, Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK. Dietary choline supplementation in pregnant rats increases hippocampal phospholipase D activity of the offspring. FASEB J. 1996;10(14):1653–9. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.14.9002559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Loy R, Heyer D, Williams CL, Meck WH. Choline-induced spatial memory facilitation correlates with altered distribution and morphology of septal neurons. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1991;295:373–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-0145-6_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strupp BJ, Powers BE, Velazquez R, Ash JA, Kelley CM, Alldred MJ, et al. Maternal choline supplementation: A potential prenatal treatment for Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. CAR. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150921100311. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas JD, Abou EJ, Dominguez HD. Prenatal choline supplementation mitigates the adverse effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on development in rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2009;31(5):303–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas JD, Biane JS, O’Bryan KA, O’Neill TM, Dominguez HD. Choline supplementation following third-trimester-equivalent alcohol exposure attenuates behavioral alterations in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121(1):120–30. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nag N, Mellott TJ, Berger-Sweeney JE. Effects of postnatal dietary choline supplementation on motor regional brain volume and growth factor expression in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Brain Res. 2008;1237:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward BC, Agarwal S, Wang K, Berger-Sweeney J, Kolodny NH. Longitudinal brain MRI study in a mouse model of Rett Syndrome and the effects of choline. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31(1):110–19. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nag N, Berger-Sweeney JE. Postnatal dietary choline supplementation alters behavior in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26(2):473–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holmes GL, Yang Y, Liu Z, Cermak JM, Sarkisian MR, Stafstrom CE, et al. Seizure-induced memory impairment is reduced by choline supplementation before or after status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2002;48(1–2):3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(01)00321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasselmo ME, Sarter M. Modes and models of forebrain cholinergic neuromodulation of cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(1):52–73. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rye DB, Wainer BH, Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Saper CB. Cortical projections arising from the basal forebrain: a study of cholinergic and noncholinergic components employing combined retrograde tracing and immunohistochemical localization of choline acetyltransferase. Neuroscience. 1984;13(3):627–43. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keeler C. Retinal degeneration in the mouse is rodless retina. J Hered. 1966;57(2):47–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelley CM, Powers BE, Velazquez R, Ash JA, Ginsberg SD, Strupp BJ, et al. Maternal choline supplementation differentially alters the basal forebrain cholinergic system of young-adult Ts65Dn and disomic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522(6):1390–410. doi: 10.1002/cne.23492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kelley CM, Powers BE, Velazquez R, Ash JA, Ginsberg SD, Strupp BJ, et al. Sex differences in the cholinergic basal forebrain in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2014;24(1):33–44. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Velazquez R, Ash JA, Powers BE, Kelley CM, Strawderman M, Luscher ZI, et al. Maternal choline supplementation improves spatial learning and adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the Ts65Dn mouse model of Down syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Detopoulou P, Panagiotakos DB, Antonopoulou S, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Dietary choline and betaine intakes in relation to concentrations of inflammatory markers in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(2):424–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeisel SH, Growdon JH, Wurtman RJ, Magil SG, Logue M. Normal plasma choline responses to ingested lecithin. Neurology. 1980;30(11):1226–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.11.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Growdon JH, Cohen EL, Wurtman RJ. Effects of oral choline administration on serum and CSF choline levels in patients with Huntington’s disease. J Neurochem. 1977;28(1):229–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb07732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wurtman RJ, Hirsch MJ, Growdon JH. Lecithin consumption raises serum-free-choline levels. Lancet. 1977;2(8028):68–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klein J, Köppen A, Löffelholz K. Small rises in plasma choline reverse the negative arteriovenous difference of brain choline. J Neurochem. 1990;55(4):1231–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen EL, Wurtman RJ. Brain acetylcholine: control by dietary choline. Science. 1976;191(4227):561–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1251187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kelley CM, Perez SE, Overk CR, Wynick D, Mufson EJ. Effect of neocortical and hippocampal amyloid deposition upon galaninergic and cholinergic neurites in AβPPswe/PS1 E9 mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25(3):491–504. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-102097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Levey AI, Armstrong DM, Atweh SF, Terry RD, Wainer BH. Monoclonal antibodies to choline acetyltransferase: production, specificity, and immunohistochemistry. J Neurosci. 1983;3(1):1–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-01-00001.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rasband WS. ImageJ. U. S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland, USA: 1997–2012. http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fonnum F. A rapid radiochemical method for the determination of choline acetyltransferase. J Neurochem. 1975;24(2):407–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1975.tb11895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW, Markesbery WR. Laminar organization of cholinergic circuits in human frontal cortex in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Neurology. 1985;35(10):1425–31. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.10.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Perez SE, He B, Muhammad N, Oh KJ, Fahnestock M, Ikonomovic MD, et al. Cholinotrophic basal forebrain system alterations in 3xTg-AD transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41(2):338–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bailey JA, Lahiri DK. Chromatographic separation of reaction products from the choline acetyltransferase and carnitine acetyltransferase assay: differential ChAT and CrAT activity in brain extracts from Alzheimer’s disease versus controls. J Neurochem. 2012;122(4):672–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mufson EJ, Counts SE, Fahnestock M, Ginsberg SD. Cholinotrophic molecular substrates of mild cognitive impairment in the elderly. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(4):340–50. doi: 10.2174/156720507781788855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mufson EJ, Ma SY, Dills J, Cochran EJ, Leurgans S, Wuu J, et al. Loss of basal forebrain P75(NTR) immunoreactivity in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443(2):136–53. doi: 10.1002/cne.10122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mufson EJ, Ma SY, Cochran EJ, Bennett DA, Beckett LA, Jaffar S, et al. Loss of nucleus basalis neurons containing trkA immunoreactivity in individuals with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427(1):19–30. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001106)427:1<19::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Counts SE, Mufson EJ. The role of nerve growth factor receptors in cholinergic basal forebrain degeneration in prodromal Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(4):263–72. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.4.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeKosky ST, Ikonomovic MD, Styren SD, Beckett L, Wisniewski S, Bennett DA, et al. Upregulation of choline acetyltransferase activity in hippocampus and frontal cortex of elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2002;51(2):145–55. doi: 10.1002/ana.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abrahám IM1, Koszegi Z, Tolod-Kemp E, Szego EM. Action of estrogen on survival of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons: promoting amelioration. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ikonomovic MD1, Abrahamson EE, Isanski BA, Wuu J, Mufson EJ, DeKosky ST. Superior frontal cortex cholinergic axon density in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(9):1312–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.9.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim I1, Wilson RE, Wellman CL. Aging and cholinergic deafferentation alter GluR1 expression in rat frontal cortex. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(7):1073–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Woolley CS, Gould E, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Naturally occurring fluctuation in dendritic spine density on adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1990;10(12):4035–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-04035.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bertoni-Freddari C, Mervis RF, Giuli C, Pieri C. Chronic dietary choline modulates synaptic plasticity in the cerebellar glomeruli of aging mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 1985;30(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(85)90054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Alfano DP, Petit TL, LeBoutillier JC. Development and plasticity of the hippocampal-cholinergic system in normal and early lead exposed rats. Brain Res. 1983;312(1):117–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(83)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Steward O, Vinsant SL. The process of reinnervation in the dentate gyrus of adult rats: a quantitative electron microscopic analysis of terminal proliferation and reactive synaptogenesis. J Comp Neurol. 1983;214:370–86. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meck WH, Williams CL, Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK. Developmental periods of choline sensitivity provide an ontogenetic mechanism for regulating memory capacity and age-related dementia. Front Integr Neurosci. 2007;1:7. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.007.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Davison JM, Mellott TJ, Kovacheva VP, Blusztajn JK. Gestational choline supply regulates methylation of histone H3, expression of histone methyltransferases G9a (Kmt1c) and Suv39h1 (Kmt1a), and DNA methylation of their genes in rat fetal liver and brain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1982–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807651200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zeisel SH. Epigenetic mechanisms for nutrition determinants of later health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1488S–93S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27113B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Aizawa S, Yamamuro Y. Involvement of histone acetylation in the regulation of choline acetyltransferase gene in NG108-15 neuronal cells. Neurochem Int. 2010;56:627–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cotman CW, Anderson KJ. Synaptic plasticity and functional stabilization in the hippocampal formation: possible role in Alzheimer’s disease. Adv Neurol. 1988;47:313–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Friedman A, Behrens CJ, Heinemann U. Cholinergic dysfunction in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:126–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ghasemi M, Hadipour-Niktarash A. Pathologic role of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in epileptic disorders: implication for pharmacological interventions. Rev Neurosci. 2015;26(2):199–223. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2014-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zeisel SH, Niculescu MD. Perinatal choline influences brain structure and function. Nutr Rev. 2006;64(4):197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zeisel SH. Importance of methyl donors during reproduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:673S–7S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26811D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Niculescu MD, Craciunescu CN, Zeisel SH. Dietary choline deficiency alters global and gene-specific DNA methylation in the developing hippocampus of mouse fetal brains. FASEB J. 2006;20(1):43–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4707com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Transposable elements: targets for early nutritional effects on epigenetic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(15):5293–300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5293-5300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Meck WH, Williams CL, Cermak JM, Blusztajn JK. Developmental periods of choline sensitivity provide an ontogenetic mechanism for regulating memory capacity and age-related dementia. Front Integr Neurosci. 2008;1:7. doi: 10.3389/neuro.07.007.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.McCann JC, Hudes M, Ames BN. An overview of evidence for a causal relationship between dietary availability of choline during development and cognitive function in offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(5):696–712. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wong-Goodrich SJ, Mellott TJ, Glenn MJ, Blusztajn JK, Williams CL. Prenatal choline supplementation attenuates neuropathological response to status epilepticus in the adult rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30(2):255–69. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]