François, Count of Enghien - Wikipedia

| François de Bourbon | |

|---|---|

| Comte d'Enghien | |

Portrait of François de Bourbon by Corneille de Lyon | |

| Successor | Jean de Bourbon, Count of Soissons and Enghien |

| Born | 23 September 1519 La Fère, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 23 February 1546 La Roche-Guyon |

| House | Bourbon-Vendôme |

| Father | Charles de Bourbon, duc de Vendôme |

| Mother | Françoise d'Alençon |

François de Bourbon, comte d'Enghien (23 September 1519 – 23 February 1546) was a French military commander, governor and prince du sang (prince of the royal blood) in the reign of king Francis I of France during the later Italian Wars. He was known by his title as the comte d'Enghien. A younger son of Charles de Bourbon, duc de Vendôme (duke of Vendôme) and Françoise d'Alençon, Enghien saw military service during the Italian War of 1542–1546. He first endeavoured to capture the city of Nice, in the Holy Roman Empire, by surprise in June 1543. This effort was foiled. Subsequently a new effort to seize Nice was launched in conjunction with the French ally, the Ottoman Empire. Though this new attempt succeeded in capturing the city of Nice, the citadel held out, and the French were forced to withdraw before it could be gained.

The following year, king Francis selected the comte d'Enghien to assume the charge of governor of the French province of Piedmont, which was threatened by the Imperial commander the marquis del Vasto. Hungry for battle, Enghien dispatched a subordinate to ask for Francis' permission to engage del Vasto, and once this was secured fought a battle with the commander on 14 April 1544. He emerged triumphant from the battle that followed and the Imperial army was broken. However, little exploitation of this victory followed, and both Enghien and his army were recalled to France to face an invasion by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Charles V enjoyed initial success in his invasion but agreed to a treaty with the French before any battle could come to pass, much to the disappointment of the heir to the French throne the Dauphin. In 1545, Enghien was greatly desirous to cross the English Channel to fight the English, but this was refused by the King. Instead he would fight in Picardy. Early in 1546, during a play fight with the favourites of the Dauphin, Enghien was struck on the head by a chest that was pushed out of a window, either in a deliberate attempt to murder him, or an accident, and he died on 23 February 1546.

Family and personal life

[edit]

François de Bourbon was born in the château de La Fère on 23 September 1519, the son of Charles de Bourbon, duc de Vendôme (duke of Vendôme) and Françoise d'Alençon.[1] Through his father he was a member of the house of Bourbon-Vendôme, a cadet branch of the French royal house of Valois.[2] His mother, Françoise, was a daughter of René de Valois, duc d'Alençon and Margaret of Lorraine.[3]

François had an elder brother, Antoine de Bourbon, born in 1518, who would go on to become the king of Navarre. He also had several prominent younger brothers including Charles de Bourbon, born in 1523, who would become first a cardinal and then be proclaimed king Charles X by the Catholic League and Louis de Bourbon, born in 1530, who would become Protestant and die at the battle of Jarnac in 1569.[4]

François de Bourbon would hold the title of comte d'Enghien (count of Enghien), by which title he would be known throughout his life. The territory of Enghien, in Hainaut, constituted part of the Luxembourg inheritance that entered the Bourbon-Vendôme family through Marie de Luxembourg, paternal grandmother to François de Bourbon.[5] In a frontier region, Enghien was vulnerable to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and would spend a period in Imperial (i.e. Holy Roman) possession before being returned to the dowager comtesse Marie in 1538 in the convention of La Fère.[6]

Around 1536, the matrimonial alliance making of the Papacy which sought the hand of Charles V's bastard daughter Margaret of Parma) was arousing alarm in France. It appeared Pope Paul III was binding his family with that Habsburgs. To assuage French fears, the Papal Nunzio Rodolfo Pio da Carpi took several approaches. He argued that the Imperial match was actually a balancing of the scales, as for the Emperor Charles V, the Farnese Popes were too French; he argued that by matching Margaret with a Farnese, they were avoiding a situation where she married Cosimo I de' Medici (future duke of Florence) thereby cementing Imperial influence over Florence; finally, the Pope was open to seeing his granddaughter Vittoria married to François de Bourbon or his elder brother Antoine de Bourbon. While negotiations for such a match would continue for the following years, nothing would come of them.[7]

First feats of arms

[edit]

Franco-Imperial war

[edit]

For the occasion of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V's visit to Paris in 1540 he enjoyed a meal alongside the French king Francis I. The two sovereigns were served at their table by several great nobles: the seigneur de Montmorency, the Constable of France took on the role of maître d'hôtel (head waiter), the comte d'Enghien served as the écuyer tranchant (the role responsible for the cutting of meat) and the comte d'Aumale served as the panetier (breadmaster).[8] Though Charles V enjoyed much hospitality from the French, it would fail to facilitate a resolution to the question of possession of the duchy of Milan.[9]

In July 1542, the French king Francis declared war on Charles V on the pretext of the murder of two envoys named Antonio Rincon and Cesare Fregoso respectively.[10]

Having entered into alliance with the Holy Roman Emperor, the English king Henry VIII declared war on France in July 1543.[11] The two enemies of France agreed that they would invade the kingdom together before 20 June 1544.[12]

The comte d'Enghien attempted a surprise assault on the Imperial county of Nice on the Mediterranean coast in June 1543, but his independent efforts were frustrated by the Genoese fleet under Andrea Doria.[13][14]

One of the only times that the Franco-Ottoman alliance was able to work coherently towards a military objective was to be found in the 1543 siege of Nice. This campaign involved the Ottoman commander Hayreddin Barbarossa, an experienced leader at the head of one of, if not the most powerful fleet in the Mediterranean on the one hand; and the young and inexperienced comte d'Enghien on the other. Enghien lacked sole command for the French, sharing the responsibility with the baron de La Garde.[15] In April 1543, the Ottoman sultan Suleiman had agreed to place his fleet at the disposal of the French following the diplomatic missions of the baron de La Garde.[16] Enghien had the specific title of lieutenant-général de l'armée de Mer du Levant (lieutenant-general of the naval army of the Levant) for the campaign.[17] The Ottoman fleet numbered some 200 ships. Barbarossa set sail for the campaign in the April of 1543 accompanied by the baron de La Garde. This force meandered its way across the Mediterranean towards the southern French coast, pillaging as it went.[18]

Barbarossa was received at the French port city of Marseille on 20 July. The French galleys, numbering 26, under the command of the comte d'Enghien went to Château d'If, on the Île d'If in the harbour of the city to meet with him. The French ships and the château saluted the arriving Ottomans with a discharge of artillery, which was responded in kind to by the Ottoman vessels. After Enghien and several others had met with Barbarossa and greeted him, the Ottoman commander travelled into Marseille to meet with king Francis.[18] Barbarossa would then spin his wheels on his ship until early August when orders arrived. The combined force was to attempt a capture of the strategic enclave of Nice that Enghien had previously been frustrated in his attempts to capture.[19]

Barbarossa's fleet was to dominate the Genoese fleet under the command of Andrea Doria, which had frustrated Enghien's prior attempt at a French conquest of Nice. Enghien's Provençal troops participated in the siege.[20] Nice was surrounded both from the land and the sea on 6 August. The following day, Ottoman soldiers and artillery disembarked at Villefranche-sur-Mer for the land operations.[16] The first assault on Nice was launched on 17 August, with the city folding without much pressure, capitulating on 22 August. The citadel of Nice was another matter though, and the resistance here was combined with the fact that Doria had set sail again to frustrate the blockade. The siege of the citadel of Nice would end in failure, the city sacked and torched as punishment before the Franco-Ottoman force withdrew. The seigneur de Vielleville pinned the blame for this brutal act on the comte de Grignan. For the naval forces, weather would be their undoing, and the Franco-Ottoman fleet was forced to take shelter by the Île Sainte-Marguerite.[19] With the attempt to subdue Nice a failure, Enghien and his men wintered in Marseille. Barbarossa, and his Ottoman men were to be quartered in the port of Toulon by royal order of 8 September. Francis was keen to see the Ottomans leave, and therefore negotiated a payment of 800,000 écus, as well as the provision of food stocks for their journey back to the Ottoman Empire.[21] As such, having tarried in Toulon, the Ottoman fleet departed back homeward in March 1544.[15]

In Sournia's estimation, Enghien did little to commend himself by his conduct during the siege of Nice.[17]

During the winter of 1543, Charles V gave his permission for the marquis del Vasto, the Imperial governor of Milan, to go on the offensive into Piedmont in north-west Italy. In November, del Vasto captured Mondovì in Piedmont before moving to besiege Carignano to the south of Turin in mid-November.[22] Carignano would fall to him. This was a major blow for the French as Carignano represented a key stronghold at the centre of French controlled Piedmont.[23] Well aware of this, del Vasto saw Carignano suitably fortified and left a strong Spanish garrison in the place.[20] Francis was frustrated by the dithering of the lieutenant-général of Piedmont, the seigneur de Boutières, to whom he had sent reinforcements, he therefore resolved to replace him.[24] [25][20]

On 26 December 1543, Enghien was established as the French lieutenant-général and governor for the province of Piedmont, replacing the seigneur de Boutières in the charge of lieutenant-général and the admiral d'Annebault as governor.[26] Annebault had already departed from Piedmont in January 1543 after a brief campaign in the area in late 1542, as the King wished to keep his favourite close. Annebault was therefore reassigned to the position of lieutenant-général of the province of Normandy. Boutières had been left in charge in the admiral's absence in 1543, he was a capable captain, but one lacking in support at the centre of royal power.[27] By contrast, Sournia describes Boutières as experienced but lazy.[25] Piedmont, a far away territory that was a recent addition to the kingdom of France, could not be left without a present governor though, hence Enghien's appointment some months later.[28] The historian Guinand notes that Enghien was the only holder of the government of French Piedmont who was not also a maréchal de France (Marshal of France - one of the chief most military offices of the kingdom).[29] The prince was only twenty four years old on his assumption of the charge.[30][31] In January 1544, the comte d'Enghien departed from Marseille to join with Boutières. Enghien arrived in Turin on 19 January to assume his new charge, having brought with him seven companies of Swiss soldiers (the Swiss mercenary had established an impressive reputation in Europe at this time).[32][25] The French position in Piedmont at this time was a broad one, controlling fifteen towns, and 27 castles, among them Turin, Pignerol and Moncalieri.[23][33] The young prince's mission, as envisioned by Francis, was to see to the recapture of Carignano.[27]

In the absence of a commissaire ordinaire des guerres or contrôleur (ordinary war commissioner or controller), Enghien was compelled to appoint 47 commissaires and 56 contrôleurs extraordinaires (commissionaires and extraordinary controllers) for the payment of his Piedmont army in January. This wide group of men were subordinated below a certain Pierre Sanson, a trésorier de l'Extraordinaire (extraordinary treasurer).[34]

During the Spring of 1544, France fought against both the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and the English king Henry VIII, with whom Charles had entered into alliance.[35] The Emperor planned a blow against Champagne, with the English to invade France and march on Paris via Calais.[36] Francis' attention was focused on the prospect of a fight in Champagne, not the fight in Piedmont.[23]

Battle or the loss of the army

[edit]

Enghien was a young man, and surrounded himself with inexperienced men who were as equally keen to partake in a major battle, even with an enemy who was superior in numbers.[26] Indeed, free of the threat of the duke of Cleves in the north, Charles V had provided a further 4,000 landsknechts for del Vasto to strike a decisive blow against the French in Piedmont.[17] Enghien did not wish to continue the tit for tat exchange of little sieges that had transpired under Boutières, feeling that it was necessary to bring things to a head, or to pull out from Piedmont.[17] Despite this resolution, the new commander put the place of Palazzolo to siege, which had been the plan of the seigneur de Boutières. From Palazzolo he advanced southwards on Carignano, encircling the settlement. Enghien determined the defences of the city were too strong for the place to be forced.[37] The approaches to the city were blocked, and the bridge over the Po river cut.[24] The siege of Carignano began in January.[35][31] A tight siege followed, cutting off those inside Carignano from any possibility of securing supplies from the cities surrounds. Meanwhile, the French army camped at Villastellone, on the other bank of the Po. In a letter of 21 March, while camped at Villastellone, Enghien noted to the comte de Crussol his displeasure at the size of the latters compagnie which was smaller than he had been lead to believe it would be.[38] From here they could see the bell tower of Carignano. Enghien was expectant of Imperial reinforcements to come to the cities aid. Around the start of March, the comte d'Enghien received notice that del Vasto was coming to relieve Carignano, and to this end was advancing on Carmagnola with his army.[31] For the French, the loss of Carmagnola would have compromised their supply situation before Carignano. Del Vasto brought to bear an army of 9,000 landsknechts (a type of German mercenary infantry), 7,000 Italians, 2,000 Spanish 1,500 light-horse and 16 artillery pieces. Enghien enjoyed an army of 15,000 infantry, 2,500 horsemen and 19 artillery pieces. In addition to these soldiers Enghien also had those involved in the blockade of Carignano and those garrisoning the various French held towns of Piedmont.[39] The pay situation for the infantry was dire, being three months in arrears when a royal agent arrived with 8,000 écus, equivalent to only one month's pay. In these circumstances, Enghien felt he could either offer battle, or see his army dissolve before his eyes. Those who survived the battle would enjoy the booty of victory, while those who did not would no longer have to be paid.[23]

Monluc and the King

[edit]

As lieutenant-général of the province of Piedmont, Enghien had full latitude to give battle as he saw fit, the choice was nevertheless a weighty one.[40] Therefore, in the hopes of finding out whether he could proffer battle to del Vasto, Enghien dispatched the seigneur de Monluc to the French court at Saint-Germain to receive the King's permission for such an enterprise. Monluc was also to acquire money to pay the armies' mercenaries.[36] Having travelled to the court in early March, the commander was compelled to cool his heels for a couple of weeks before he met with the King and his council of war perhaps some time in mid-March. Enghien received no word from Monluc during the wait, and therefore dispatched a new courier to appraise the King of the several thousand extra troops that del Vasto had recently acquired, but noting that he was still waiting for more to arrive.[17] Our one account of the meeting that followed between Monluc and Francis' royal council, is the famous colourful rendition of the proceedings from the seigneur de Monluc himself. Sournia cautions that it is quite likely to be an embellished one.[41] Attendant for the proceedings were the King, his eldest surviving son the dauphin (future king Henri II, the comte de Saint-Pol, the admiral d'Annebault, the grand écuyer Galiot de Genouillac and the seigneur de Boisy who would succeed Galiot de Genouillac to the charge of grand écuyer (grand squire). The meeting began with Monluc being told by the King that he should impress upon the commanders in Piedmont that it was already the decided opinion of Francis and his council that Enghien could not give battle.[26] Francis then yielded the floor to Saint-Pol, who raised the ominous spectre of the imminent invasion of the kingdom by the English king and the Emperor. It would be a disaster for the kingdom in such circumstances if Enghien lost an army (filled with the kingdom's best infantry, with only inexperienced légionnaires being within the borders) in Piedmont.[41] Saint-Pol was followed by similar speeches from the other councillors including the admiral d'Annebault.[42] Nawrocki contrasts the priorities of Enghien and his young captains, hungry to test their courage in battle with men of state like d'Annebault.[43] Giving battle was a major risk in the circumstances. A loss in Piedmont could compromise the Italian frontier. Nawrocki argues it would have been more prudent to pursue a defensive posture and re-allocate soldiers from Piedmont to more pressing theatres such as Champagne. While Galiot de Genouillac was speaking his opposition to the proposal, Monluc was overwhelmed with need to interrupt. The comte de Saint-Pol bade Monluc be quiet, causing the King to laugh.[44] Francis then addressed Monluc, asking him if he appreciated the direction of the council he had heard. Monluc retorted that he indeed understood, but wished for leave from Francis to speak himself, to make an alternate case. Francis bade Monluc speak his mind. Enghien's representative began by detailing the troops present in Piedmont, among whom were 5,600 Gascons, Provençals, thirteen Swiss ensigns numbering as strongly as the Gascons, Italians, Gruyèrians, four hundred men-at-arms and six hundred light horse. Combined these numbered around nine or ten thousand infantry, with a further one thousand to twelve hundred horse. These soldiers were, in Monluc's estimation, the real deal as opposed to a theoretical army strength.[41] Monluc outlined the desire of the captains and soldiery to see battle, noting that with courage a smaller army could triumph over a greater one.[45] The Dauphin, who was standing behind the King, laughed and encouraged Monluc onwards. The captain regaled Francis with his past military achievements, and highlighted that, if battle was not given, the resolve of the King's soldiers would evaporate.[46] Francis looked to Saint-Pol, who proceeded to deride Monluc as foolhardy with a lust for battle that overrode strategic considerations. After Monluc again plead for battle, Saint-Pol despaired of the King, seeing him won over to the argument of Monluc.[47] Francis now turned to Annebault asking him for his opinion. The admiral with diplomatic tact replied that he observed the King favoured battle, and that he personally could not assert any particular result from the affair and that the King should look to god to decide on the matter. Overall, Saint-Pol offered wise council to his sovereign, but it was wise council that flew in the face of how the King was increasingly feeling about the whole affair. The admiral d'Annebault saw advantage in Enghien giving battle, for the strong hand that it could give France against Genoa, but he also saw the risks, and thus did not openly declare himself for Monluc's position. Nawrocki also notes that Annebault had recent experience of command of Enghien's army, back from when he was governor of Piedmont.[48] Convinced of the course, Francis threw his hat on the table and cried Qu'ils combattent! Qu'ils combattent! (Let them fight! Let them fight!).[49][50] After this outburst from the King, Annebault noted to Monluc that if Enghien and his captains saw defeat in Piedmont it would be on their heads alone, but if they saw victory, it would likewise be on their heads.[51] Francis gave instructions to Annebault as concerned Enghien, as well as the allocation of funds that Monluc would bring back to the young prince.[46] As Monluc took his leave of the council, he found by the door many young gentleman keen to learn whether permission to fight would be granted.[44] Monluc bade them enter quickly if they wished to gain permission from the King to join the fight.[52] The Dauphin for one was desperate to join with Enghien for the coming battle, but permission for this was not granted by Francis. The King in general did not proffer his permission without resistance. Some men of the court therefore left to join with Enghien having acquired royal leave to do so, others left without leave.[49] Monluc would return with a suite of the Dauphin's young favourites: the seigneur de Saint-André, the seigneur de Jarnac, the seigneur de Dampierre, the seigneur de Châtillon and the vidame de Chartres.[35][31] The son of Galiot de Genouillac, who had counselled against battle, a certain seigneur d'Assier would also take the road to join with Enghien.[52] Annebault's seventeen-year-old son Jean d'Annebault also departed the court to join Enghien's battle.[48] Some of these young men, hungry for combat, would be killed in the campaign.[53]

Before having heard the result of Monluc's mission, on 5 April, Enghien moved his army to Carmagnola, to better control access to Carignano.[40] Monluc subsequently returned to Enghien, communicating to the commander the decision the King had resolved upon. In addition to this he appraised Enghien of the young nobles come to join with him.[53] These nobles numbered around a hundred, and were all untested in 'great battle'. Some of these noblemen were only weakly equipped, or totally lacking in equipment. Such was not a universal state of affairs, and the seigneur d'Assier, for example, enjoyed command of his compagnie d'ordonnance and all the necessary equipment.[39] Another experienced arrival was the seigneur de Boutières, who, frustrated by his replacement at the hands of Enghien, had returned to the theatre at the head of his compagnie of 50 lances (a lance fournie was the French unit of heavy cavalry, each consisting of the heavy cavalryman and several supporting soldiers).[54]

The seigneur de Langey travelled to Piedmont from Paris with 48,000 écus (crowns) for Enghien's army. Having passed the Alps his journey was a treacherous one, forced to make passage close to Imperial held Carignano before he could arrive in the French camp with his funds.[55] His arrival, on 11 April, was greeted with much pleasure by the army. However, the backlog of the armies pay amounted to around 207,900 livres (pounds), and this sum was insufficient to cover it. Therefore, Enghien assured his men of future pay to come.[54]

Holding out the prospect of a potential future full pay, Enghien promised his men that they just needed to fight and then they would receive the money they were due.[54] The army began the march the next day. Around this time, del Vasto was marching on Ceresole near Cuneo. He hoped by this measure to force the river Po and take Carmagnola from the west, the only plausible direction of attack, so that the French besiegers of Carignano might be both without food and money.[53] At daybreak 13 April, the French army also looked to make for Ceresole, Enghien was unaware of the Imperial disposition at this time, only knowing that the prior day the Imperials had been camped at Montà around 20km from Carmagnola.[54] The French vanguard was under the command of the seigneur de Thermes, with 4,000 infantry and 200 light horse' the battle (the central of the divisions of armies of this period) of the army was under the comte d'Enghien's command, and consisted of much of the elite nobility, as well as 4,000 Swiss confederates; to Enghien's south, the seigneur de Dampierre commanded the rearguard of the guidons, archers and a further 3,000 infantry of Gruyères.[56]

Scouts were sent out to get a clearer picture of where the Imperials were located. Among the scouts were 200 light horse, including the seigneur de Monluc. With their return, a consensus was formed that del Vasto was close.[57] His route was not as clear as his position, making the decision of how to oppose him a more contentious one among the command. A small portion of the army was allocated to reconnoitre the area while the majority remained put around Carmagnola. This group stumbled across del Vasto and the Imperial army making their way from Ceresole to Sommariva del Bosco. Thanks to these efforts, Enghien gained full understanding of the Imperial position by the mid-afternoon of 13 April. An fr:escarmouche (skirmish between two advanced guards) followed, which saw the engagement of the French arquebusiers.[58] The order was given to form up, the Imperials regrouping around Ceresole to face the French. Del Vasto who was at Sommariva returned to Ceresole when he heard the news. By the time he met up with his men, night was drawing in. Enghien met with his captains to discuss the matter, and it was agreed that it was too late in the day, what with much of the army still being before Carmagnola.[59] Therefore, they withdrew to Carmagnola for the night, much to the regret of some soldiers who wished to remain in their positions. Among those who bitterly regretted the withdrawal was Monluc, who had been involved in the escarmouche during the afternoon.[60] In the French camp, heated debate was had, with Monluc getting fired up.[61] The army stewed through the evening and into the early morning in a state of tension. After a brief rest, Enghien ordered his men draw up for battle again at 01:00 in front of Carmagnola. Here the army stays for the next two hours under the light of torches.[60] With Del Vasto holding tight in Ceresole, Enghien made his departure from Carmagnola around 03:00 on the morning of 14 April with the aim of blocking an Imperial march at Sommariva.[56] Scouts uncover the Imperial position, still around Cerisole, and therefore Enghien orders his army make for a nearby plateau. As the sun rose the two sides squared off against one another on the field.

Disposition of the forces

[edit]

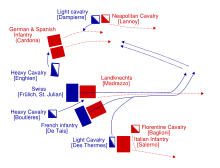

The lines were arrayed north to south across from one another. The French were to the west, and the Imperials the east. To the northern (i.e. left-most) extreme of the French line was the seigneur de Dampierre's 700 light cavalry. To the southernmost extreme (i.e. right-most) were to be found the 450 cavalry of the seigneur de Thermes and de Monal. In between these two cavalry forces were the armies vanguard, battle and rearguard. In the south, abutting against the cavalry of de Thermes, were the Gascon infantry and the French old bands of Piedmont.[62] The latter were, in one contemporary opinion, the best French infantry the kingdom had.[63] The left flank of this block of infantry was protected by compagnies d'ordonnance, that of the comte de Tende and the seigneur de Boutières, numbering around 100 men-at-arms. In the French centre was to be found the comte d'Enghien and a block of 4,000 Swiss under the command of the captain Frölich. Enghien has with him around 600 cavalry, including several compagnies d'ordonnance such as that of the seigneur d'Assier, the comte de Crussol and the seigneur de Montreval. Also with Enghien in the centre were around 100 light cavalry and the many young nobles of the court who had followed the clarion call of Monluc (such as the sieur de Châtillon and the seigneur d'Andelot. North of Enghien, were a group of around 6,000 containing the Swiss of the comte de Gruyères under the command of the seigneur de Cugy, as well as Provençals and Italians under the command of the governor of French held Mondovì de Dros. Finally, scattered in front of the whole line, under the command of the seigneur de Mailly, were to be found 19 artillery pieces.[64][35][31][36]

Del Vasto had disposed of his men much as had Enghien. His light cavalry was to be found on the extremes of his two wings. On the Imperial right were 650 horseman of the prince of Sulmona.[65] Meanwhile, on the left were 400 horseman under Rodolfo Baglioni. One of the commanders the French faced off against was the prince of Salerno at the head of around 6,000 Italians. He was located opposite the Gascons of the French line. Salerno would, in the coming year, fall out with the Emperor and enter French service.[66][67] Four thousand German and Gascon soldiers under a certain Ramondo de Cardona faced off against the French left. In the Imperial centre were to be found 7,000 German landsknechts. As with the French the fifteen artillery pieces of the Imperial army were spread out before the army.[65]

In contrast to battles of earlier eras, both sides deployed with an integration between the cavalry and the infantry. The dangers of firearms had brought to an end the times when the heavy cavalry would seek to open the battle with a charge. Rather the order of the day by the time of Ceresole was to shield the cavalry behind the infantry, who would bear the first brunt. The cavalry would then enter the combat at a later point, targeting areas of crisis and importance.[68] Due to the divisions of the army at Ceresole, three separate battles would be fought, one by each section of the army.[69]

The two armies stared at each other throughout the morning of 14 April. Enghien and del Vasto both took the opportunity to liaise with their captains during this period. As part of these consultations, Monluc was awarded control of all the arquebusiers in the old bands.[70] The battle began with an artillery duel, which lasted for three hours and was viciously contested. Early in the afternoon, there was a skirmish of arquebusiers, between those of the old band under the seigneur de Monluc and those of the Imperial right of the prince of Salerno.[70] This battle focused around the southernmost limit of the battle line, at the Alfiere cascina near the plateau.[71] Having captured the cascina, control of it was in flux for the next few hours, each side alternating possession until it was finally definitively won by the Imperials. Throughout this action the French artillery had thundered away, supporting Monluc's arquebusiers in the south and firing on the German and Spanish infantry in the north. Due to the distance between the two armies the French artillery achieved little.[72] Indeed the French had hoped to site their artillery on the cascina.[73] This combat came to an end at around 16:00. With the Imperial artillery near the cascina now in a position where it might actually threaten the old bands, this induced in them the desire to advance rather than continue to be subject to attacks.[72] The light cavalry of the French and Imperial wings now surged forward into a new combat.[74] On the French right, the cavalry of the seigneur de Thermes crashed into the Italian cavalry facing them, scattering Baglioni's force. In the north, the seigneur de Dampierre enjoyed similar success against the Imperial cavalry of the prince of Sulmona.[75][76] This success was not uncomplicated however, in the headiness of the advance, de Thermes' cavalry got tangled with the prince of Salerno's pikeman, with Thermes being unhorsed and captured. Meanwhile, the seigneur de Dampierre was forced to reorganise after his advance.[77]

While the French cavalry was advancing, much of their infantry remained motionless. This was not the same in the Imperial camp, which began two parallel movements. Near the north of the line, the Spanish and German veteran infantry began moving forward to fight the Gruyères, Provençal and Italian royal infantry. Further down the line, the fifteen bands of German landsknechts in Imperial service made their advance.[77]

The advance of the northern veteran infantry against Enghien's part of the line overran the French artillery batteries in their path, with horses and gunners killed, and ammunition torched. Meanwhile, to the south, the old bands of French infantry had been intending to advance on Salerno's Italians but were now faced with the advance of the landsknechts on their left flank. They therefore moved to confront this advancing force, as did the landsknechts longtime rivals, the Swiss.[77] As the two sides enmeshed with one another in a push of pikes, the Imperial landsknechts counted on their numbers to allow them move against the flanks of their opponents. The French meanwhile worked to broaden their front.[78][67] In addition to the pikes, Gascon arquebusiers were also involved in this melee.[79] The French came out of this melee well, pushing the landsknechts back and inducing heavy casualties.[61]

The aim of the Imperial advance in the north was to isolate the Swiss of Enghien's centre.[67] The French left wing fell into crisis. The Gruyères infantry collapsed with the Imperial onslaught. As the Gruyères infantry fled back into the Provençal and Italian infantry of the sieur de Dros they too were thrown into chaos and flight. Some of the French baggage also departed the field.[67] The Spanish infantry were thus able to cleave their way through them. With this local triumph on the field, the Spanish and German veteran infantry hoped to swing into the French flanks, like had been accomplished with great effect at the battle of Pavia. The poor performance of the Gruyères earned them the apathy of the French.[80][67]

It was now that the French gendarmerie undertook two charges. The one, a hundred men-at-arms led by the seigneur de Boutières against that of the marquis del Vasto; the other by the comte d'Enghien against the Spanish of the centre left. Del Vasto was perched on the rightmost edge of the German landsknechts and, faced with Boutières charge his force withdrew.[81] Exploiting their success, Boutières gendarmes now looked to support the Swiss and French infantry in their fight with the landsknechts. This strike was delivered effectively against the rear rows of the landsknechts. The cavalries success was imitated by the men of the seigneur de Thermes. Together these efforts doomed the landsknechts, which fell into a state of panic.[82] Neither the Florentines nor the forces of the prince of Salerno intervened to support the landsknechts.[61] Surrounded, the landsknecht force was cut to pieces. Knives were used to kill the wounded. Those landsknechts that had thrown down their weapons and surrendered, were killed by the Swiss.[83][84] Even landsknechts that had fallen into the hands of those that wished to spare them were cut down. Guinand notes that this violence was not unusual, particularly between the Swiss and landsknechts, who were rivals.[85] The pursuit of the landsknechts terminated in front of Ceresole when word arrived that part of the Imperial army had yet to be defeated.[86]

Elsewhere on the battlefield, Enghien's charge brought together 600 cavalrymen in several waves of what Sournia describes as "imprudent" strikes. They looked to hit at the flank of the Spanish infantry. However, by this point the Spanish were developing the system of the tercio which combined the use of arquebuses and pikes. This was not the same kind of infantry as the French might have faced in prior decades. Enghien's charge was able only to break a corner of the Spanish formation, but could not shake the wider unit.[87] Among those shot in the first wave was the seigneur d'Assier. Many of the French horses were killed in the attack, including that which belonged to Enghien. Unable to deliver the decisive blow he had envisioned, even with the support of the forces of the seigneur de Dampierre, the Imperial infantry continued its pursuit of the routing French left. In Pellegrini's estimation, Enghien's charge kept open the possibility of French victory. Indeed, this is the opinion of the contemporary memoirist du Bellay, who argues that Enghien's force temporarily slowed del Vasto's old bands, which was critical for stopping them from marching into the rear of the Swiss and Gascons and bringing about an Imperial victory.[88] Due to rises and falls in the ground, Enghien's ability to command the wider French army and know the state of the broader battle was lost as soon as he began his charge. He was therefore unaware of the destruction of the German landsknechts and the withdrawal of Salerno's Italians in the wake of the landsknechts defeat.[87] With this limited information, Enghien despaired the battle as having been lost.[83][69] Enghien began to withdraw towards Carmagnola, however he was intercepted by his maître de camp (camp master) Saint-Julien who urged him to turn around, as his army was victorious and not defeated.[89]

The Imperial right of the Spanish and German soldiers, now found themselves sandwiched between the returning elements of the French left who had been retreating from the battlefield, and the Gascon and Swiss bands who had terminated their pursuit towards Ceresole. Realising they were advancing alone, and having been appraised of the defeat of the rest of the Imperial army, the Imperial right halted itself.[90] This force now began to retreat, pursued by Enghien's cavalry, as well as some infantry that had rallied. The force faced the French infantry coming from Ceresole. After a little while, much of this force surrendered.[91] Knowing they would find small mercy at the hands of the infantry, the Spanish and German infantry worked to surrender to the French cavalry, crowding around them.[90]

The prince of Salerno ordered a retreat. The battle concluded with the pursuit of those Imperials who were still withdrawing until night fell.[91][76]

The battle was a bloody one, with many left dead. According to a French account written the day after the battle, between 9,000 and 10,000 Imperials had been killed during the course of the battle. This source claimed that the French for their part lost 900 men of whom 400 were men-at-arms and 500 were infantry. The historian Le Fur dismisses these figures, but argues that we will likely never know the true totals. Sournia by contrast lends credence to them, arguing the Imperials suffered 12,000 dead, to several hundred French. Pellegrini favours the more moderate total of 6,000 or 7,000 Imperial dead.[84] Three thousand German landsknechts were made prisoners.[83] Enghien desired to convert some captured Italians to the French cause.[92] Among the prisoners, the leader of the Imperial vanguard Carlo Gonzaga. The more elite captains were maintained in the hope of trade for French captives (such as the seigneur de Thermes). Meanwhile, the mercenary infantry in Imperial service was allowed to return home with little consideration given to them.[93] The Imperial commander, the marquis del Vasto had twice been wounded in the combat, having received a mace wound to his hand, and another wound to his left knee.[89] He had to withdraw to Asti to recuperate.[76][94] Del Vasto's, and thus Charles V's, position in Italy was compromised for a long time by the defeat.[95] The son of the admiral d'Annebault, who commanded fifty lances, distinguished himself during the battle under Enghien's command.[96] After the battle, Enghien embraced Monluc, and then knighted him in an anachronistic ceremony recalling those of the medieval period. Another noble that received knighting on the field of Ceresole was the seigneur de Châtillon.[97] This would be the last recorded instance of such a knighting on the field.[84] Monluc recorded this moment in his memoires.[98] The seigenur de Monluc would be rich in praise for the comte d'Enghien, though he considered his charges during the battle to be foolhardy.[99][100][101]

Among the loot acquired from the battle was a great deal of money the Imperials had with them, 10,000 écus. By these funds, the arrears of pay to the Swiss and Italian soldiers could partially be honoured. 4,000 padlocks were also found in the Imperial baggage, supposedly because del Vasto had dreamed of sending captives he made to the galleys.[102] So much armour, 7,000 or 8,000 corselets, was taken as profit from the battle that the price of armour in the region tumbled.[93]

Monluc requested of Enghien the right to be the one to travel to the French court to inform Francis of the victory at Ceresole. Enghien ignored this wish, dispatching instead the comte d'Escars with a letter to the King announcing the victory, wounding the feelings of Monluc.[100][103] Though dispatched with a letter, he primarily left the elaborating on the course of the battle for Escars to communicate verbally.[104] Frustrated at his spurning, Monluc therefore asked Enghien to be relieved, so that he might return to Gascony. Enghien permitted this, though asked that he return to Piedmont with around a thousand men for the army.[105] Guinand notes that the French army had suffered casualties of around 16% or more of their force, and thus this mission Enghien sent Monluc on was necessary to maintain their numbers.[103] Another envoy, Hercules Visconti was entrusted with informing the French ambassadors in Rome, Venice, and Mirandola with the news by Enghien.[104]

In the wake of his triumph at Ceresole, the comte d'Enghien enjoyed a pre-eminent position among the French nobility. Durot describes Enghien as the only noble capable of overshadowing the comte d'Aumale. Enghien received an ode from the famous poet Pierre Ronsard entitled La victoire de François de Bourbon Comte d'Enghien, à Cérisoles (The victory of François de Bourbon, comte d'Enghien at Ceresole).[99] He would enjoy the considerable affection of king Francis, for whom the victory represented another Marignano.[106][84] Sournia offers a derisory account of Enghien's triumph. In his estimation, the battle was a chaotic mess over which Enghien was ill-appraised and lacking in skill.[61] The triumph, for Sournia, belonged "indisputably" to the infantry of the French army.[83]

Spoiled fruits of victory

[edit]

Enghien desired to march on Asti after this victory, while some of his subordinates, like the seigneur de Monluc yearned to strike at Milan, which for the first time since the 1520s lay almost undefended.[104] Word soon arrived back with the army from the French crown that an advance on Milan could not be sanctioned. Enghien would be granted some money to pay his Swiss, and would be able to continue the siege of Carignano, but no more.[104] Cloulas suspects the Dauphin was greatly desirous to see a march forward into Milan come to pass for the Piedmont army, and that to this end he and his wife Catherine were thus kept appraised of Italian developments by Piero Strozzi.[31] Nawrocki frames this episode somewhat differently. He argues that it was Enghien's novice inexperience that foiled the chance to exploit the victory by a quick march on Milan. The contemporary historian du Bellay noted that, had this come to pass, Charles V would have had to move his forces south into Italy rather than invading France.[48]

It would not be possible to follow up on this victory of Ceresole. Unable to march onto Milan, Enghien entrusted 200 men-at-arms and the artillery under the command of de Thais with the occupation of marquisate of Montferrat, which they succeeded in conquering with the exception of Casale, Alba and Trino.[107] In April, Charles V undertook preparations to invade France either into Picardy or Champagne. According to Le Fur, 16,000 French soldiers were recalled from Piedmont to aid in the defence of the north-west. Crété suggests that 12,000 foot soldeirs were recalled from Piedmont.[108] The defeated prince of Salerno exacted his revenge by defeating Piero Strozzi, who unlike Enghien looked to advance into the Milanese with troops he had assembled at Mirandola, at Serravelle on 4 June.[94][107] Knecht describes this Imperial victory as having annulled that achieved by the French at Ceresole.[50] The comte d'Enghien kept only enough soldiers to continue the siege of Carignano. He was supplemented in June by the forces Monluc had recruited in France.[109] Finally, on 21 June, the commander of Carignano, Piero Colonna capitulated to the French.[95] He surrendered to Enghien on the understanding his men would be able to march out with their weapons, if without their ensigns. Colonna himself was to enter French service within 8 days.[104] A dual invasion of France was now beginning, with the Imperials marching into Champagne after easily overthrowing the French in Luxembourg, and Henry VIII joining an English siege of Boulogne in the north on 14 July just as had been predicted during Monluc's meeting with the King.[31][109][110] Thus, Enghien and his soldiers were recalled to deal with this crisis.[35] The final act of Enghien's army in Piedmont was to capture the town of Alba at the end of July. To this end he had commanded Strozzi's force to join with him. On 8 August, a three-month truce with del Vasto was established, bringing to an end the war in Piedmont.[111][107]

Invasion of Champagne

[edit]

Having invaded France, on 8 July, the Imperial commander Ferrante Gonzaga laid siege to the city of Saint-Dizier. He was soon joined by Charles V, who brought the rest of the Imperial army.[112] Through the capture of Saint-Dizier, the road to Paris could be opened.[109] Saint-Dizier resisted the Imperials well, and it looked as though soon Charles V would have to withdraw. Around this time, Francis was suffering from a major illness and therefore his eldest surviving son, the Dauphin, was granted lead of the military operations against the Emperor. Charles V was to be found in the Marne valley, while the royal army was in Champagne. The comte d'Enghien, who had come north, was raring to fight the Emperor alongside the Dauphin. A major reverse came for the French when the cipher codes the French used fell into Imperial hands, and Charles V used them to get the garrison of Saint-Dizier commander to surrender in August.[35] Knecht does not mention this reason for Saint-Dizier's composition, arguing that munitions were running out in the city and that they sought to surrender on honourable terms.[112] The Emperor then marched on Château-Thierry which was put to the torch on 9 September. Charles V edged closer to Paris, getting as close as 20 leagues from the city. The royal army, under the Dauphin's command looked to place itself in between their adversary and the capital around La Ferté-sous-Jouarre. Inside Paris, panic reigned. Though the Emperor was close to Paris, this proximity hid the vulnerability of his army. He revealed to his sister, the queen of France Eleanor that it was not possible for him to maintain the prosecution of the war beyond the end of September, and she looked to bring about a peace. Much to the fury of the Dauphin who felt victory was within his grasp, negotiations began on 12 September.[113]

On 18 September, peace arrived with the Imperials in the treaty of Crépy. By the terms of this accord, the youngest son of the French King, the duc d'Orléans, would enjoy an Imperial marriage in which he would receive either the Netherlands or the Franche Comté as his brides dowry. The French were to abandon their claims to Savoy and Piedmont, as well as their Swiss and Protestant German allies while the Emperor abandoned his claim to the duchy of Burgundy.[35] The Dauphin signed this treaty.[114]

After retreating to Anet to meet with his mistress Diane, the Dauphin resolved to make formal protest against the renunciations mandated of him by the treaty of Crépy: specifically the renunciations of the kingdom of Naples, the duchy of Milan, the county of Asti, as well as Flanders and Artois on thr northern frontier. To this end he drew up a protest at the château de Fontainebleau on 12 December. This protest received several illustrious co-signatories, who served as witnesses, among them two princes du sang (the duc de Vendôme and his uncle the comte d'Enghien) and the comte d'Aumale. Aumale's father, the duc de Guise dared not sign the protest for fear of reprisals. He need not have worried however as the document would remain a secret.[115][114] Nawrocki argues that the Dauphin had probably already resolved on voiding the treaty upon his accession as king (something which would come to pass in 1547 when he ascended the throne as Henri II).[116]

War continued with England, and to this end several armies were sent out at the start of 1545: one to Scotland, a second to invade the Isle of Wight, and a third to conduct the fight in Picardy. The naval army which was being prepared for the cross-sea attack contained French nobles such as the seigneur de Boutières, de Thais and the vidame de Chartres. Enghien and the comte d'Aumale were eager to involve themselves in the enterprise, however Francis refused them permission.[33] The naval campaign was felt to be too dangerous for young knights of such lineage.[117] The main event of the Picard theatre was the siege of English held Boulogne, which was led by the maréchal du Biez.[115] The royal vanguard in Picardy was under the command of the comte de Brissac. In the vanguard were to be found the compagnies of the comte d'Enghien, the comte d'Aumale and the duc de Nevers among others. All these men partook in skirmishes with the English facilitated by the proximity of the royal camp to the fortifications of Boulogne.[118] There would be no climactic fight with the English however.[119] While the French army engaged in these actions, du Biez looked to end the siege of Boulogne favourably, so that he might move on to compromise the English positions in Calais and Guînes.[120]

With the constable de Montmorency in royal disgrace after 1541, his charge of governor of the province of Languedoc was laid vacant. The comte d'Enghien would serve as governor in his stead from 1545 until his death.[121][122][123] Harding records the start of his tenure as governor of Languedoc as instead being 15 December 1544.[124]

It was a favoured custom of the young nobility to engage in mock fights.[125] One such fight transpired on 18 February 1546, between two parts of the entourage of the Dauphin at the château de La Roche-Guyon. Enghien led the defence of the castle which was assaulted by the comte d'Aumale and the seigneur d'Albon. The sides had agreed they would only use snowballs as projectiles for this combat. Nevertheless, while Enghien who had been tired by the combat, rested beneath a window in the courtyard of the château after the conduct of a sortie, the young comte was struck on the head with a chest dropped from the window by a certain favourite of the Dauphin, the fuorusciti (Italian exile) Cornelio Bentivoglio.[126][127][128]

For several days, the comte d'Enghien lingered in a coma. He died on 23 February 1546. It is not known whether this chest was dropped with malicious or accidental intent. The contemporary memoirist du Bellay characterised the event as a clumsy error, while Brantôme and de Thou saw a deliberate murder in the act.[128] Enghien had previously had a hot dispute with Cornelio Bentivoglio. As a result of this dispute, Bentivoglio fell under suspicion of having murdered Enghien. Bentivoglio in turn had ties with the comte d'Aumale. Francis did not permit an investigation to proceed in any case. It was alleged the investigations was quashed by the King out of fear that the Dauphin himself, or the comte d'Aumale might be implicated of having been involved, jealous of the glory Enghien had cloaked himself in at Ceresole.[126] The Italian exile Bentivoglio would thus be first driven from the French court, before being pardoned and permitted to return.[127] Though no favourite of the Dauphin's would see serious consequences, Francis' opinions of them became ones of revulsion.[128]

On the same day as his death, 23 February 1546, Enghien was succeeded as lieutenant-général and governor of Languedoc by Galiot de Genouillac.[123]

Enghien's younger brother, the comte de Soissons inherited Enghien's company of 50 lances by the terms of a royal brêvet.[129] He also inherited the eponymous comté d'Enghien from Enghien.[130]

For Decrue, the comte d'Enghien was the most illustrious brother of the duc de Vendôme (later king of Navarre).[131] Quilliet argues that Enghien enjoys relative obscurity, due to his young death.[132]

- Baumgartner, Frederic (1988). Henry II: King of France 1547–1559. Duke University Press.

- Cloulas, Ivan (1979). Catherine de Médicis. Fayard.

- Cloulas, Ivan (1985). Henri II. Fayard.

- Constant, Jean-Marie (1984). Les Guise. Hachette.

- Crété, Liliane (1985). Coligny. Fayard.

- Decrue, Francis (1889). Anne, Duc de Montmorency: Connétable et Pair de France sous les Rois Henri II, François II et Charles IX. E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie.

- Durot, Éric (2012). François de Lorraine, duc de Guise entre Dieu et le Roi. Classiques Garnier.

- Foletier, François de Vaux de (1925). Galiot de Genouillac: Maître de L'Artillerie de France (1465 – 1546). Auguste Picard.

- Guinand, Julien (2020). La Guerre du Roi aux Portes de l'Italie: 1515-1559. Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Harding, Robert (1978). Anatomy of a Power Elite: the Provincial Governors in Early Modern France. Yale University Press.

- Jouanna, Arlette (2009). La France de La Renaissance. Perrin.

- Jouanna, Arlette (2021a). La France du XVIe Siècle 1483-1598. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Jouanna, Arlette (2021b). "BOURBON, maison de". In Jouanna, Arlette; Hamon, Philippe; Biloghi, Dominique; Le Thiec, Guy (eds.). La France de La Renaissance: Histoire et Dictionnaire. Bouquins.

- Knecht, Robert (1994). Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I. Cambridge University Press.

- Knecht, Robert (1996). The Rise and Fall of Renaissance France. Fontana Press.

- Knecht, Robert (2008). The French Renaissance Court. Yale University Press.

- Le Fur, Didier (2018). François Ier. Perrin.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2015). Le Crépuscule de la Chevalerie: Noblesse et Guerre au Siècle de la Renaissance. Champ Vallon.

- Michon, Cédric (2018). François Ier: Un Roi Entre Deux Mondes. Belin.

- Nawrocki, François (2015). L'Amiral Claude d'Annebault: conseiller favori de François Ier. Classiques Garnier.

- Pellegrini, Marco (2017). Le Guerre d'Italia 1494-1559. Società Editrice il Mulino.

- Potter, David (1992). "The Luxembourg Inheritance: The House of Bourbon and its lands in Northern France during the Sixteenth Century". French History. 6 (1).

- Potter, David (1995). A History of France 1460-1560: The Emergence of a Nation State. Macmillan.

- Potter, David (2008). Renaissance France at War: Armies, Culture and Society c. 1480 – 1560. Boydell Press.

- Quilliet, Bernard (1998). La France du Beau XVIe Siècle. Fayard.

- Romier, Lucien (1909). Jacques d'Albon de Saint-André: Maréchal de France (1512 – 1562). Perrin et Cie.

- Sainte-Marie, Anselme de (1733). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France, des pairs, grands officiers de la Couronne, de la Maison du Roy et des anciens barons du royaume: Tome I. La compagnie des libraires.

- Shaw, Christine; Mallett, Michael (2019). The Italian Wars 1494-1559: War, State and Society in Early Modern Europe. Routledge.

- Shimizu, J. (1970). Conflict of Loyalties: Politics and Religion in the Career of Gaspard de Coligny, Admiral of France, 1519–1572. Geneva: Librairie Droz.

- Sournia, Jean-Charles (1981). Blaise de Monluc: Soldat et Écrivain (1500-1577). Fayard.

- Tallon, Alain (2018). "François Ier et Paul III". In Amico, Juan Carlos d'; Fournel, Jean-Louis (eds.). François Ier et l'Espace Politique Italien: États, Domaines et Territoires.

- ^ Jouanna 2009, p. 734.

- ^ Jouanna 2021b, pp. 648–649.

- ^ Sainte-Marie 1733, pp. 328–329.

- ^ Jouanna 2021b, p. 649.

- ^ Potter 1992, p. 30.

- ^ Potter 1992, p. 32.

- ^ Tallon 2018, p. 309.

- ^ Knecht 2008, p. 140.

- ^ Knecht 2008, p. 141.

- ^ Jouanna 2021a, p. 181.

- ^ Potter 1995, p. 271.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 214.

- ^ Knecht 1996, p. 213.

- ^ Shaw & Mallett 2019, p. 226.

- ^ a b Michon 2018, p. 253.

- ^ a b Knecht 1994, p. 487.

- ^ a b c d e Sournia 1981, p. 70.

- ^ a b Le Fur 2018, p. 830.

- ^ a b Le Fur 2018, p. 831.

- ^ a b c Guinand 2020, p. 48.

- ^ Le Fur 2018, p. 853.

- ^ Pellegrini 2017, p. 198.

- ^ a b c d Le Fur 2018, p. 954.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 262.

- ^ a b c Sournia 1981, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Nawrocki 2015, p. 295.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 79.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 503.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 62.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cloulas 1985, p. 120.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 291.

- ^ a b Nawrocki 2015, p. 343.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cloulas 1979, p. 73.

- ^ a b c Crété 1985, p. 40.

- ^ Shaw & Mallett 2019, p. 227.

- ^ Potter 2008, p. 316.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 264.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Sournia 1981, p. 71.

- ^ Romier 1909, p. 29.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 259.

- ^ a b Foletier 1925, p. 115.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 296.

- ^ a b Sournia 1981, p. 72.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Nawrocki 2015, p. 299.

- ^ a b Romier 1909, p. 30.

- ^ a b Knecht 1994, p. 490.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 298.

- ^ a b Foletier 1925, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Sournia 1981, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Guinand 2020, p. 265.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 189.

- ^ a b Le Fur 2018, p. 855.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 71.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 266.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 267.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 268.

- ^ a b c d Sournia 1981, p. 74.

- ^ Potter 2008, p. 151.

- ^ Potter 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 269.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 270.

- ^ Cloulas 1985, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d e Le Fur 2018, p. 856.

- ^ Pellegrini 2017, p. 199.

- ^ a b Pellegrini 2017, p. 200.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 271.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 272.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 274.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 273.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 275.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 276.

- ^ a b c Le Fur 2018, p. 857.

- ^ a b c Guinand 2020, p. 277.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 279.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 280.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 281.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 282.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 283.

- ^ a b c d Sournia 1981, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Pellegrini 2017, p. 201.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 286.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 287.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 284.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 289.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 285.

- ^ a b Shaw & Mallett 2019, p. 228.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 288.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 290.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 292.

- ^ a b Sournia 1981, p. 79.

- ^ a b Le Fur 2018, p. 858.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 486.

- ^ Shimizu 1970, p. 15.

- ^ Le Roux 2015, p. 44.

- ^ a b Durot 2012, p. 46.

- ^ a b Sournia 1981, p. 76.

- ^ Potter 2008, p. 259.

- ^ Le Fur 2018, p. 357.

- ^ a b Guinand 2020, p. 293.

- ^ a b c d e Guinand 2020, p. 294.

- ^ Sournia 1981, p. 77.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Shaw & Mallett 2019, p. 229.

- ^ Crété 1985, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Sournia 1981, p. 80.

- ^ Knecht 1994, pp. 490–491.

- ^ Guinand 2020, p. 295.

- ^ a b Knecht 1994, p. 491.

- ^ Cloulas 1985, p. 121.

- ^ a b Baumgartner 1988, p. 37.

- ^ a b Cloulas 1985, p. 124.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 332.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 344.

- ^ Cloulas 1985, p. 125.

- ^ Le Fur 2018, p. 889.

- ^ Cloulas 1985, p. 126.

- ^ Decrue 1889, p. 4.

- ^ Nawrocki 2015, p. 614.

- ^ a b Foletier 1925, p. 140.

- ^ Harding 1978, p. 224.

- ^ Sournia 1981, p. 98.

- ^ a b Cloulas 1985, p. 127.

- ^ a b Durot 2012, p. 47.

- ^ a b c Romier 1909, p. 37.

- ^ Potter 2008, p. 108.

- ^ Potter 1992, p. 50.

- ^ Decrue 1889, p. 16.

- ^ Quilliet 1998, p. 103.