Genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles in urothelial carcinomas and urothelia at the precancerous stage

Abstract

To clarify genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles during multistage urothelial carcinogenesis, bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA) was performed in 18 normal urothelia obtained from patients without urothelial carcinomas (UCs) (C), 17 noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs (N), and 40 UCs. DNA hypo‐ and hypermethylation on multiple BAC clones was observed even in N compared to C. Principal component analysis revealed progressive DNA methylation alterations from C to N, and to UCs. DNA methylation profiles in N obtained from patients with invasive UCs were inherited by the invasive UCs themselves, that is DNA methylation alterations in N were correlated with the development of more malignant UCs. The combination of DNA methylation status on 83 BAC clones selected by Wilcoxon test was able to completely discriminate N from C, and diagnose N as having a high risk of carcinogenesis, with 100% sensitivity and specificity. The combination of DNA methylation status on 20 BAC clones selected by Wilcoxon test was able to completely discriminate patients who suffered from recurrence after surgery from patients who did not. The combination of DNA methylation status for 11 BAC clones selected by Wilcoxon test was able to completely discriminate patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter who suffered from intravesical metachronous UC development from patients who did not. Genome‐wide alterations of DNA methylation may participate in urothelial carcinogenesis from the precancerous stage to UC, and DNA methylation profiling may provide optimal indicators for carcinogenetic risk estimation and prognostication. (Cancer Sci 2009)

It is known that DNA hypomethylation results in chromosomal instability as a result of changes in chromatin structure, and that DNA hypermethylation of CpG islands silences tumor‐related genes in cooperation with histone modification in human cancers.( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ) Accumulating evidence suggests that alterations of DNA methylation are involved even in the early and the precancerous stages.( 6 , 7 ) On the other hand, in patients with cancers, aberrant DNA methylation is significantly associated with poorer tumor differentiation, tumor aggressiveness, and poorer patient outcome.( 6 , 7 ) Therefore, alterations of DNA methylation may play a significant role in multistage carcinogenesis.

With respect to urothelial carcinogenesis, we have reported accumulation of DNA methylation on C‐type CpG islands in a cancer‐specific but not age‐dependent manner, and protein overexpression of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1, a major DNMT, even in noncancerous urothelia with no apparent histological changes obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs).( 8 , 9 ) Moreover, accumulation of DNA methylation on C‐type CpG islands associated with DNMT1 protein overexpression was more frequently evident in aggressive nodular invasive UCs( 8 , 9 , 10 ) resulting in poorer patient outcome than in superficial papillary UCs, which usually remain noninvasive even after repeated urethrocystoscopic resection.( 11 , 12 ) Since aberrant DNA methylation is one of the earliest molecular events during urothelial carcinogenesis and also participates in tumor aggressiveness, it may be possible to estimate the future risk of developing more malignant UCs. However, only a few previous studies focusing on UCs( 13 ) have employed recently developed array‐based technology for assessing genome‐wide DNA methylation status,( 14 , 15 , 16 ) and such studies have focused on identification of tumor‐related genes that are silenced by DNA methylation.( 13 ) DNA methylation profiles, which could become the optimum indicators for carcinogenetic risk estimation and prognostication of UCs, should therefore be explored using array‐based approaches.

In this study, in order to clarify genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles during multistage urothelial carcinogenesis, we performed bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA)( 17 , 18 , 19 ) using a microarray of 4361 BAC clones( 20 ) in normal urothelia obtained from patients without UCs, noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs, and UCs themselves.

Materials and Methods

Patients and tissue samples. Seventeen samples of noncancerous urothelia (N1–N17) and 40 samples of UCs (T1–T40) of the urinary bladder, ureter, and renal pelvis were obtained from specimens that had been surgically resected by radical cystectomy (12 patients) or nephroureterectomy (28 patients) at the National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. The patients comprised 31 men and nine women whose mean age was 69.03 ± 9.77 (mean ± SD) years (range, 49–85 years). Microscopic examination revealed no remarkable histological changes in the noncancerous urothelia. The patients from whom noncancerous urothelia were obtained comprised 11 men and six women with a mean age of 70.41 ± 9.33 (mean ± SD) years (range, 49–85 years). There were 17 superficial UCs (two pTa and 15 pT1 tumors) and 23 invasive UCs (six pT2, 16 pT3, and one pT4 tumor) according to the criteria proposed by World Health Organization classification.( 21 ) For comparison, 18 samples of normal urothelia obtained from patients without UCs (C1–C18) were used. Fourteen, three, and one patient underwent nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma, nephrectomy for retroperitoneal sarcoma around the kidney, and partial cystectomy for urachal carcinoma, respectively. The patients from whom normal urothelia were obtained comprised 13 men and five women with a mean age of 61.17 ± 15.16 (mean ± SD) years (range, 27–82 years). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan and has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in 1995. All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in this study.

BAMCA. High‐molecular‐weight DNA from fresh frozen tissue samples was extracted using phenol‐chloroform, followed by dialysis. Because DNA methylation status is known to be organ‐specific,( 22 ) the reference DNA for analysis of the developmental stages of UCs should be obtained from the urothelium, and not from other organs or peripheral blood. Therefore, a mixture of normal urothelial DNA obtained from 11 male patients (C19–C29) and six female patients (C30–C35) without UCs was used as a reference for analyses of male and female test DNA samples, respectively. DNA methylation status was analyzed by BAMCA using a custom‐made array (MCG Whole Genome Array‐4500) harboring 4361 BAC clones located throughout chromosomes 1–22, X and Y,( 20 ) as described previously.( 17 , 18 , 19 ) Briefly, 5‐μg aliquots of test or reference DNA were first digested with 100 units of the methylation‐sensitive restriction enzyme Sma I and subsequently with 20 units of the methylation‐insensitive Xma I. Adapters were ligated to the Xma I‐digested sticky ends, and PCR was performed with an adapter primer set. Test and reference PCR products were labeled by random priming with Cy3‐ and Cy5‐dCTP (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK), respectively, and precipitated together with ethanol in the presence of Cot‐I DNA. The mixture was applied to array slides and incubated at 43°C for 72 h. Arrays were scanned with a GenePix Personal 4100A (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) and analyzed using GenePix Pro 5.0 imaging software (Axon Instruments) and Acue 2 software (Mitsui Knowledge Industry, Tokyo, Japan). The signal ratios were normalized in each sample to make the mean signal ratios of all BAC clones 1.0.

Statistics. Differences in the average number of BAC clones that showed DNA methylation alterations (DNA hypo‐ and hypermethylation) between groups of samples were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U‐test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered significant. Principal component analysis based on BAMCA data was performed using the Expressionist software program (Gene Data, Basel, Switzerland). Unsupervised two‐dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis of tissue samples and the BAC clones were performed using the Expressionist software program. Correlations between the subclassification of patients yielded by unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis and clinicopathological parameters of UCs were analyzed using the χ2‐test. Differences at P < 0.05 were considered significant. BAC clones whose signal ratios yielded by BAMCA were significantly different between groups of samples were identified by Wilcoxon test (P < 0.01).

Results

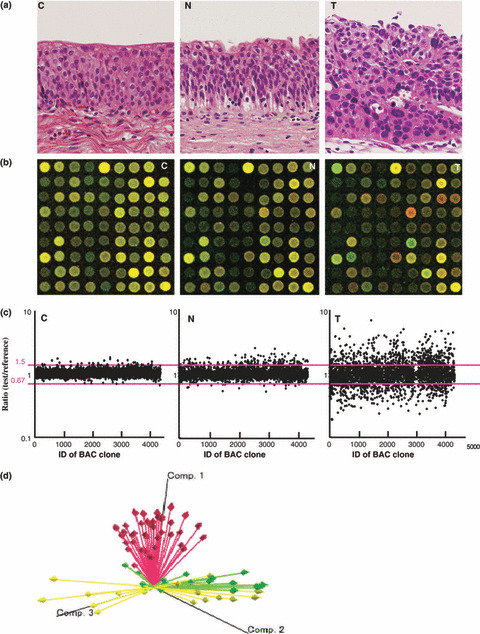

Genome‐wide DNA methylation alterations during multistage urothelial carcinogenesis. Figure 1(b,c) shows examples of scanned array images and scattergrams of the signal ratios (test signal/reference signal), respectively, for normal urothelium from a patient without UC (panel C), and both noncancerous urothelium (panel N) and cancerous tissue (panel T) from a patient with UC. In all normal urothelia (C1–C18), the signal ratios of 97% of the BAC clones were between 0.67 and 1.5 (red bars in Fig. 1c). Therefore, in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs and UCs, DNA methylation status corresponding to a signal ratio of less than 0.67 and more than 1.5 was defined as DNA hypomethylation and DNA hypermethylation of each BAC clone compared to normal urothelia, respectively, as in our previous study.( 23 ) In noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs, many BAC clones showed DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation (panel N of Fig. 1c). In UCs themselves, more BAC clones showed DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation, and the degree of DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation, that is deviation of the signal ratio from 0.67 or 1.5, was increased (panel T of Fig. 1c) in comparison with noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs. The average number of BAC clones showing DNA hypomethylation increased significantly from noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs (24.53 ± 31.48) to UCs (236.78 ± 92.78, P = 4.37e‐9). The average number of BAC clones showing DNA hypermethylation increased significantly from noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs (29.18 ± 39.84) to UCs (289.13 ± 82.42, P = 7.35e‐9). Principal component analysis based on BAMCA data (signal ratios) revealed progressive DNA methylation alterations from normal urothelia, to noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs, and to UCs (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

DNA methylation alterations during multistage urothelial carcinogenesis. (a) Microscopic view of normal urothelium obtained from a patient without urothelial carcinoma (UC) (C), noncancerous urothelium obtained from a patient with UC (N), and UC (T). N shows no remarkable histological changes in comparison to C, that is no cytological or structural atypia is evident. Hematoxylin–eosin staining. Original magnification, ×20. (b) Scanned array images obtained by bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA) in C, N, and T. Co‐hybridization was done with test and reference DNA labeled with Cy3 and Cy5, respectively. (c) Scattergrams of the signal ratios (test signal/reference signal) obtained by BAMCA in C, N, and T. In all 18 normal urothelia (C1–C18), the signal ratios of 97% of the BAC clones were between 0.67 and 1.5 (red bars). Therefore, in N and T, DNA methylation status corresponding to a signal ratio of less than 0.67 and more than 1.5 was defined as DNA hypomethylation and DNA hypermethylation on each BAC clone compared to C, respectively. Even though N did not show any marked histological changes in comparison to C (panels C and N in [a]), many BAC clones showed DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation. In T, more BAC clones showed DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation, whose degree, that is deviation of the signal ratio from 0.67 or 1.5, was increased in comparison to N. (d) Principal component analysis based on BAMCA data (signal ratios). Progressive alterations of DNA methylation status from normal urothelia (yellow arrows) to noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs (green arrows), and to UCs (red arrows) were observed.

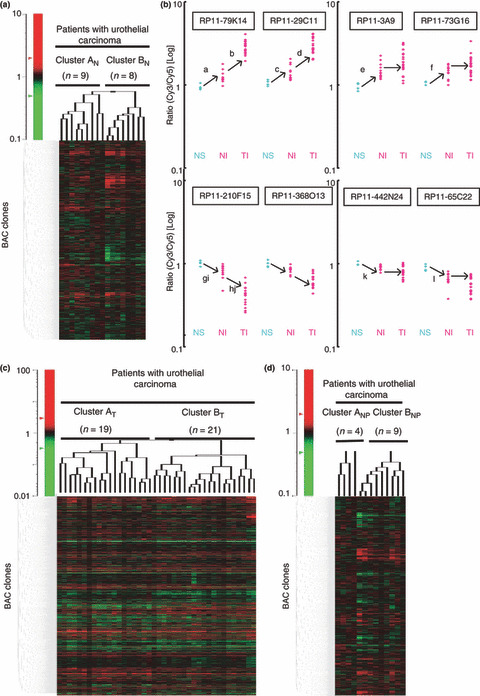

Clinicopathological significance of DNA methylation alterations in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with Ucs. In order to clarify the clinicopathological significance of DNA methylation alterations in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs, unsupervised two‐dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis based on BAMCA data (signal ratios) for noncancerous urothelia was performed. Seventeen patients with UCs were clustered into two subclasses, Clusters AN and BN, which contained nine and eight patients, respectively, based on the DNA methylation status of the noncancerous urothelia (Fig. 2a). All eight patients (100%) belonging to Cluster BN suffered from invasive UCs (pT2 or more), whereas five (55.6%) of the patients belonging to Cluster AN did so (P = 0.0311).

Figure 2.

Correlations between DNA methylation status and clinicopathological parameters. (a) Unsupervised two‐dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis based on bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA) data (signal ratios) in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs). The signal ratio is shown in the color range map. Seventeen patients with UCs were hierarchically clustered into two subclasses, Clusters AN (n = 9) and BN (n = 8). Eight patients (100%) belonging to Cluster BN developed invasive UCs (pT2 or more), whereas five patients (55.6%) belonging to Cluster AN did so (P = 0.0311). (b) Scattergrams of the signal ratios in tissue samples. NS, noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with superficial UCs. NI, noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs. TI, invasive UCs. If the average signal ratios in NI were significantly higher than those in NS, the average signal ratios in TI themselves were even higher than (BAC clones RP11‐79K14 and RP11‐29C11), or not significantly different from (BAC clones RP11‐3A9 and RP11‐73G16), those in NI without exception. If the average signal ratios in NI were significantly lower than those in NS, the average signal ratios in TI themselves were even lower than (BAC clones RP11‐210F15 and RP11‐368O13), or not significantly different from (BAC clones RP11‐442N24 and RP11‐65C22), those in NI without exception. a P = 0.001680673, b P = 9.23504e‐7, c P = 0.002197802, d P = 3.64223e‐6, e P = 0.000840336, f P = 0.007692306, g P = 0.004395604, h P = 8.31509e‐6, i P = 0.004395604, j P = 1.10173e‐5, k P = 0.005882353, l P = 0.001098901. (c) Unsupervised two‐dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis based on BAMCA data (signal ratios) in UCs. Forty patients with UCs were hierarchically clustered into two subclasses, Clusters AT (n = 19) and BT (n = 21). All four patients with recurrence belonged to Cluster BT. (d) Unsupervised two‐dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis based on BAMCA data (signal ratios) for noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter. Thirteen patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter were hierarchically clustered into two subclasses, Clusters ANP (n = 4) and BNP (n = 9). All four patients who developed intravesical metachronous UC belonged to Cluster BNP.

The Wilcoxon test (P < 0.01) revealed that the signal ratios of 131 BAC clones differed significantly between noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with superficial UCs (pTa and pT1) and noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs (pT2 or more). If the average signal ratios in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs were significantly higher than those in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with superficial UCs (67 BAC clones), the average signal ratios in the invasive UCs themselves were even higher than (42 BAC clones, e.g. RP11‐79K14 and RP11‐29C11 in Fig. 2b) or not significantly different from (25 BAC clones, e.g. RP11‐3A9 and RP11‐73G16 in Fig. 2b) those in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs, without exception. If the average signal ratios in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs were significantly lower than those in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with superficial UCs (64 BAC clones), the average signal ratios in the invasive UCs themselves were even lower than (38 BAC clones, e.g. RP11‐210F15 and RP11‐368O13 in Fig. 2b) or not significantly different from (26 BAC clones, e.g. RP11‐442N24 and RP11‐65C22 in Fig. 2b) those in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs, without exception, that is DNA methylation status of the 131 BAC clones in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs was inherited by the invasive UCs themselves.

DNA methylation profiles discriminating noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs from normal urothelia. Our finding that DNA methylation alterations in noncancerous urothelia were correlated with the development of UCs, as described above, prompted us to estimate the degree of carcinogenetic risk based on DNA methylation profiles in noncancerous urothelia. We attempted to establish criteria for indicating that noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs, and not normal urothelia, were at high risk of carcinogenesis.

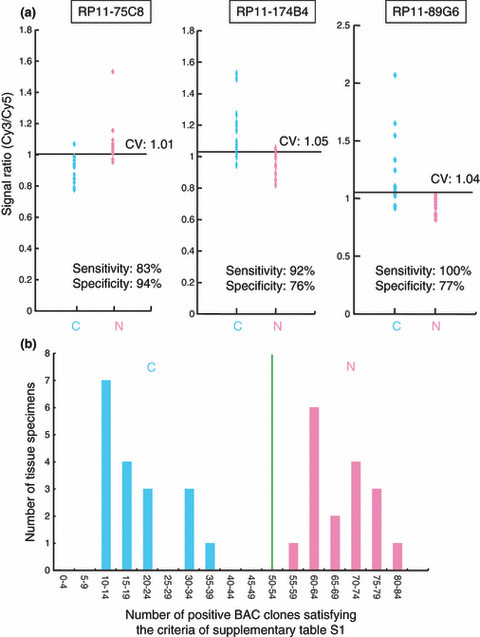

The Wilcoxon test (P < 0.01) revealed that the signal ratios on 201 BAC clones differed significantly between normal urothelia obtained from patients without UCs and noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs. Figure 3(a) shows scattergrams of the signal ratios in normal urothelia and noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs for representative examples of the 201 BAC clones. Using the cut‐off values described in Figure 3(a), noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs were discriminated from normal urothelia with sufficient sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 3a). From the 201 BAC clones, 83 for which such discrimination was performed with a sensitivity and specificity of 75% or more than 75% were selected (Table S1). The cut‐off values of the signal ratios for the 83 BAC clones, and their sensitivity and specificity, are shown in Table S1.

Figure 3.

DNA methylation profiles discriminating noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) (N) from normal urothelia (C). (a) Scattergrams of the signal ratios in C and N on representative bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones, RP11‐75C8, RP11‐174B4, and RP11‐89G6. Using the cut‐off values (CV) described in each panel, N in this cohort were discriminated from C with sufficient sensitivity and specificity. (b) Histogram showing the number of BAC clones satisfying the criteria listed in Table S1 in samples C1–C18 and N1–N17. Based on this histogram, we established a criterion that when the noncancerous urothelia satisfied the criteria in Table S1 for 50 (green bar) or more than 50 BAC clones, they were judged to be at high risk of carcinogenesis.

A histogram showing the number of BAC clones satisfying the criteria listed in Table S1 for 18 normal urothelia (C1–C18) and 17 noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs (N1–N17) is shown in Figure 3(b). Based on this figure, we finally established the following criteria: when noncancerous urothelia satisfied the criteria in Table S1 for 50 or more BAC clones (green bar in Fig. 3b), they were judged to be at high risk of carcinogenesis, and when noncancerous urothelia satisfied the criteria in Table S1 for less than 50 BAC clones, they were judged not to be at high risk of carcinogenesis. Based on these criteria, both the sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs in this cohort as being at high risk of carcinogenesis were 100%.

Association of DNA methylation profiles in UCs with recurrence. Unsupervised two‐dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis based on BAMCA data (signal ratios) for UCs was able to group 40 patients into two subclasses, Clusters AT and BT, which contained 19 and 21 patients, respectively (Fig. 2c). Four patients (19.0%) belonging to Cluster BT suffered recurrence after surgery (metastasis to the pelvic lymph nodes in three, and metastasis to the lung and bone in one), whereas none (0%) belonging to Cluster AT did so (P = 0.0449). The mean observation period was 29.8 ± 28.0 months (mean ± SD). These data prompted us to establish criteria for predicting recurrence of UCs based on DNA methylation status.

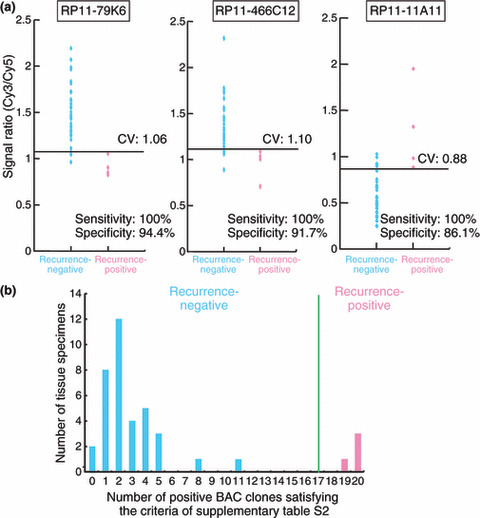

The Wilcoxon test (P < 0.01) revealed that the signal ratios on 20 BAC clones in UCs differed significantly between the patients who suffered recurrence after surgery and patients who did not. Figure 4(a) shows scattergrams of the signal ratios in UCs obtained from patients who suffered recurrence and those in UCs obtained from patients who did not. DNA methylation status of the 20 BAC clones was able to discriminate patients who suffered recurrence from patients who did not with a sensitivity of 100% using the cut‐off values shown in Figure 4(a) and Table S2. A histogram showing the number of BAC clones satisfying the criteria listed in Table S2 for all 40 UCs is shown in Figure 4(b). Satisfying the criteria in Table S2 for 17 or more BAC clones (green bar in Fig. 4b) discriminated patients who suffered recurrence from patients who did not with a sensitivity and specificity of 100%, whereas high histological grade,( 21 ) invasive growth (pT2 or more), and vascular or lymphatic involvement were unable to achieve such complete discrimination (data not shown).

Figure 4.

DNA methylation profiles in urothelial carcinomas (UCs) associated with recurrence. (a) Scattergrams of the signal ratios in UCs from patients who did not develop recurrence (n = 36) and UCs from patients who developed recurrence (n = 4) on representative bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC), clones, RP11‐79K6, RP11‐466C12, and RP11‐11A11. Using the cut‐off values (CV) described in each panel, recurrence‐positive patients were discriminated from recurrence‐negative patients with 100% sensitivity. (b) Histogram showing the number of BAC clones satisfying the criteria listed in Table S2 in all 40 patients with UCs. Satisfying the criteria in Table S2 for 17 (green bar) or more than 17 BAC clones discriminated recurrence‐positive patients from recurrence‐negative patients with a sensitivity and specificity of 100%, whereas high histological grade (21), invasive growth (pT2 or more), and vascular or lymphatic involvement were unable to achieve such complete discrimination (data not shown).

Association of DNA methylation profiles in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter with intravesical metachronous UC development. It is well known that patients with UCs of the renal pelvis and ureter frequently suffer from metachronous UC development in the urinary bladder after nephroureterectomy.( 24 , 25 ) Since such metachronous UC originates from the noncancerous urothelium of the urinary bladder, we focused on the DNA methylation status of noncancerous urothelia obtained by nephroureterectomy from patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter. Unsupervised two‐dimensional hierarchical clustering analysis based on BAMCA data (signal ratios) for noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter was able to group 13 patients into two subclasses, Clusters ANP and BNP, which contained four and nine patients, respectively (Fig. 2d). Four (44%) of the patients in Cluster BNP developed intravesical metachronous UCs, whereas none (0%) belonging to Cluster ANP did so. These data prompted us to establish criteria that could predict the development of intravesical metachronous UC based on DNA methylation status.

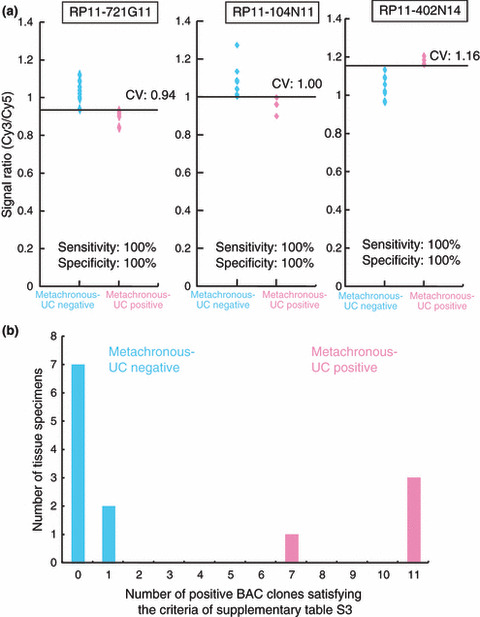

The Wilcoxon test (P < 0.01) revealed that the signal ratios on 11 BAC clones in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter differed significantly between patients who developed intravesical metachronous UC after nephroureterectomy and patients who did not. DNA methylation status of nine of the 11 BAC clones was able to discriminate patients who suffered from intravesical metachronous UC development from patients who did not with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% using the cut‐off values shown in Figure 5(a) and Table S3. A histogram showing the number of BAC clones satisfying the criteria listed in Table S3 for 13 noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter is shown in Figure 5(b).

Figure 5.

DNA methylation profiles in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) of the renal pelvis or ureter associated with intravesical metachronous UC development. (a) Scattergrams of the signal ratios in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients who did not develop intravesical metachronous UCs (n = 9) and noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients who developed intravesical metachronous UCs (n = 4) on representative bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones, RP11‐721G11, RP11‐104N11, and RP11‐402N14. Using the cut‐off values (CV) described in each panel, metachronous UC‐positive patients were discriminated from metachronous UC‐negative patients with 100% sensitivity and specificity. (b) Histogram showing the number of BAC clones satisfying the criteria listed in Table S3 in all 13 patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter from whom noncancerous urothelia were obtained. Patients who were negative and positive for metachronous UC were confirmed to show a marked difference in the DNA methylation status of the 11 BAC clones.

Discussion

Urothelial carcinomas are clinically remarkable because of their multicentricity: synchronously or metachronously multifocal UCs often develop in individual patients. A possible mechanism for such multiplicity is the “field effect,” whereby carcinogenic agents in the urine cause malignant transformation of multiple urothelial cells.( 26 ) Even noncancerous urothelia showing no remarkable histological features obtained from patients with UCs can be considered to be at the precancerous stage, because they may be exposed to carcinogens in the urine. On the other hand, UCs are classified as superficial papillary carcinomas or nodular invasive carcinomas according to their configuration. Superficial papillary carcinomas usually remain noninvasive, although patients need to undergo repeated urethrocystoscopic resections because of recurrences. In contrast, the clinical outcome of nodular invasive carcinomas is poor.( 11 , 12 )

In our previous study, accumulation of DNA methylation on C‐type CpG islands associated with DNMT1 protein overexpression was observed even in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs.( 8 , 9 ) Aberrant DNA methylation was further increased, especially in nodular invasive carcinomas.( 8 , 9 , 10 ) These previous data suggested that carcinogenetic risk estimation and prognostication of UCs based on DNA methylation status might be a promising strategy. Although optimal diagnostic indicators have never been explored using array‐based genome‐wide DNA methylation analysis, alterations of DNA methylation on several CpG islands in UCs have been reported separately.( 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 )

Many researchers in the field of cancer epigenetics have used promoter arrays to identify the genes that are methylated in cancer cells.( 14 , 15 , 16 ) However, the promoter regions of specific genes are not the only target of DNA methylation alterations in human cancers. DNA methylation status in genomic regions that do not directly participate in gene silencing, such as the edges of CpG islands, may be altered at the precancerous stage before the alterations of the promoter regions themselves occur.( 32 ) Genomic regions in which DNA hypomethylation affects chromosomal instability may not be contained in promoter arrays. Moreover, aberrant DNA methylation of large regions of chromosomes, which are regulated in a coordinated manner in human cancers due to a process of long‐range epigenetic silencing, has recently attracted attention.( 33 ) Therefore, we used a custom‐made BAC array( 20 ) that may be suitable for gaining an overview of the DNA methylation status of individual large regions among all chromosomes (Table S4), and for obtaining reproducible diagnostic indicators. In fact we have successfully obtained optimal indicators for carcinogenetic risk estimation and prognostication of renal cell carcinomas( 23 ) and hepatocellular carcinomas( 34 ) by BAMCA using the same array as that employed in this study. On the other hand, we must pay attention to the quantitative accuracy of BAMCA, because it is a PCR‐based method differing from other genome‐wide DNA methylation analyses not using PCR, such as the methylated DNA immunoprecipitation‐microarray. In order to validate the results of BAMCA, we quantitatively evaluated the DNA methylation status of each Xma I/Sma I site yielding labeled products which are effective in BAMCA on representative BAC clones, by pyrosequencing. As shown in the example in Figure S1 and Table S5, pyrosequencing validated the BAMCA data on the representative BAC clone.

The present DNA methylation analysis revealed that stepwise DNA methylation alterations during urothelial carcinogenesis occurred in a genome‐wide manner (Fig. 1). We then performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis based on the genome‐wide DNA methylation status of noncancerous urothelia, and as a result, 17 patients were subclassified into Clusters AN and BN. Corresponding UCs showing deeper invasion were found to be accumulated in Cluster BN. Genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles of noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with invasive UCs were inherited by the invasive UCs themselves (Fig. 2b). DNA methylation profiles of noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with superficial UCs were not always inherited by superficial UCs (data not shown), corresponding to the alternative malignant progression of superficial papillary carcinoma to nodular invasive carcinoma, via papillo‐nodular carcinoma. Genome‐wide DNA methylation alterations that were correlated with the development of more malignant invasive cancers were already accumulated in noncancerous urothelia, suggesting that DNA methylation alterations at the precancerous stage may not occur randomly but are prone to further accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations and generate more malignant cancers.

The present genome‐wide analysis revealed DNA methylation profiles that were able to completely discriminate noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs from normal urothelia and diagnose them as having a high risk of urothelial carcinogenesis with a sensitivity and specificity of 100%. We are currently attempting to develop methodology for assessing the tendency for DNA methylation in the 83 BAC regions in urine samples with a view to application for screening of healthy individuals. If it proves possible to identify individuals who are at high risk of urothelial carcinogenesis, then strategies for the prevention or early detection of UCs, such as smoking cessation or repeated urine cytology examinations, might be applicable.

Even after surgery with curative intent, some UCs relapse and metastasize to lymph nodes or distant organs.( 35 ) Recently, new systemic chemotherapy and targeted therapy have been developed for treatment for UCs.( 36 ) In order to start adjuvant systemic chemotherapy immediately in patients who have undergone surgery and are still at high risk of recurrence and metastasis, prognostic indicators have been explored. The present genome‐wide analysis revealed DNA methylation profiles that were able to discriminate patients who suffered recurrence after surgery from patients who did not with a sensitivity and specificity of 100% (Fig. 4b), whereas a high histological grade,( 21 ) invasive growth (pT2 or more), and vascular or lymphatic involvement, which are known to have a prognostic impact,( 37 , 38 ) were incapable of such complete discrimination (data not shown). Therefore, a combination of the 20 BAC clones can have significant prognostic value for patients with UCs. Since a sufficient quantity of good‐quality DNA can be obtained from each surgical specimen, our array‐based analysis that overviews aberrant DNA methylation of each BAC region is immediately applicable to routine laboratory examinations for prognostication after surgery. The reliability of such prognostication will need to be validated in a prospective study.

As mentioned above, UCs are remarkable because of their multicentricity. Approximately 10–30% of patients with UCs of the renal pelvis and ureter develop intravesical metachronous UCs after nephroureterectomy.( 24 , 25 ) Therefore, such patients have to undergo repeated urethrocystoscopic examinations to detect intravesical metachronous UCs. To decrease the need for invasive urethrocystoscopic examinations and assist close follow‐up of such patients after nephroureterectomy, indicators for intravesical metachronous UCs have been needed. All of our patients who developed intravesical metachronous UCs after nephroureterectomy belonged to Cluster BNP, indicating that DNA methylation profiles of noncancerous urothelia obtained by nephroureterectomy from patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter, which may be exposed to the same carcinogens in the urine as noncancerous urothelia from which metachronous UCs originate, are correlated with the risk of intravesical metachronous UC development. The present genome‐wide analysis revealed DNA methylation profiles that were able to completely discriminate patients with UCs of the renal pelvis or ureter who developed intravesical metachronous UCs from patients who did not, in noncancerous urothelia from nephroureterectomy specimens. A combination of the present 11 BAC clones may be an optimal indicator for the development of intravesical metachronous UC. The reliability of such prognostication will again need to be validated in a prospective study.

With respect to background factors of genome‐wide DNA methylation alterations during urothelial carcinogenesis, smoking history did not correlate significantly with the numbers of BAC clones showing DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs and in UCs, or with clustering (Cluster AN vs Cluster BN and Cluster AT vs Cluster BT) (Table S6). In addition, immunohistochemically examined DNMT1 protein expression levels did not correlate significantly with the numbers of BAC clones showing DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs and in UCs, or with clustering (Cluster AN vs Cluster BN and Cluster AT vs Cluster BT) (Table S7), indicating that expression levels of DNMT1 did not by themselves simply determine DNA methylation profiles. However, our previous study revealed remarkable protein overexpression of DNMT1 in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs as compared to normal urothelia.( 8 ) Therefore, undefined cofactors may recruit DNMT1 or other proteins regulating DNA methylation status to aberrant target sequences and may participate in DNA methylation alterations in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs. Further studies are needed to elucidate molecular mechanisms of DNA methylation alterations in such noncancerous urothelia.

Moreover, when the DNA methylation status for CpG islands of p16, human MutL homologue 1 (hMLH1), thrombospondin‐1 (THBS‐1), and death‐associated protein kinase (DAPK) genes and the methylated in tumor (MINT)‐1, ‐2, ‐12, ‐25, and ‐31 clones were examined in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs and in UCs by methylation‐specific PCR and combined bisulfite restriction enzyme analysis as in our previous study,( 9 , 39 ) the incidence of DNA methylation on each CpG island and the average number of methylated CpG islands did not correlate significantly with the numbers of BAC clones showing DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with UCs and in UCs, or with clustering (Cluster AN vs Cluster BN and Cluster AT vs Cluster BT) (Table S8). Therefore, molecular mechanisms for alterations of genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles may differ from those for regional DNA hypermethylation on CpG islands.

Although BAMCA mainly provides an overview of the DNA methylation status of individual large regions among all chromosomes as mentioned above, it may also be able to identify genes for which expressions are regulated by DNA methylation, since there are promoter regions of specific genes including CpG islands on BAC clones showing clinicopathologically significant DNA hypo‐ or hypermethylation (Table S4). Expression levels and the DNA methylation status of these genes, as well as the functions of the proteins coded by such genes, will be examined in a future investigation. If further studies identify tumor‐related genes for which expression levels are regulated by DNA methylation among such candidates, these tumor‐related genes may serves as targets for epigenetic prevention and therapy, along with the molecules causing alterations of genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Examples of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA) data validation by pyrosequencing.

Table S1. Eighty‐three bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that were able to discriminate noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) (N) from normal urothelia (C) with a sensitivity and specificity of 75% or more.

Table S2. Twenty bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that were able to discriminate urothelial carcinomas (UCs) in patients who developed recurrence (Pos) from those in patients who did not (Neg).

Table S3. Eleven bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that were able to discriminate noncancerous urothelia in patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) of the renal pelvis or ureter who developed intravesical metachronous UC (Pos) from those in patients who did not (Neg).

Table S4. Genes, CpG islands in the promoter regions, and repeat elements of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones in Tables S1, S2, and S3.

Table S5. Primer sets for validation study by pyrosequencing.

Table S6. Correlation between smoking history and DNA methylation status in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) and UCs.

Table S7. Correlation between protein expression levels of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 and DNA methylation status in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) and UCs.

Table S8. Correlation between regional DNA hypermethylation on CpG islands and the results of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA) in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) and UCs.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Grant‐in‐Aid for the Third Term Comprehensive 10‐Year Strategy for Cancer Control from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan; a Grant‐in‐Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan; a Grant from the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO); and the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NiBio). N. Nishiyama is an awardee of a research resident fellowship from the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research in Japan.

References

- 1. Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2002; 3: 415–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eden A, Gaudet F, Waghmare A, Jaenisch R. Chromosomal instability and tumors promoted by DNA hypomethylation. Science 2003; 300: 455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baylin SB, Ohm JE. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer – a mechanism for early oncogenic pathway addiction? Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6: 107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gronbaek K, Hother C, Jones PA. Epigenetic changes in cancer. Apmis 2007; 115: 1039–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feinberg AP. Phenotypic plasticity and the epigenetics of human disease. Nature 2007; 447: 433–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kanai Y, Hirohashi S. Alterations of DNA methylation associated with abnormalities of DNA methyltransferases in human cancers during transition from a precancerous to a malignant state. Carcinogenesis 2007; 28: 2434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanai Y. Alterations of DNA methylation and clinicopathological diversity of human cancers. Pathol Int 2008; 58: 544–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nakagawa T, Kanai Y, Saito Y, Kitamura T, Kakizoe T, Hirohashi S. Increased DNA methyltransferase 1 protein expression in human transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol 2003; 170: 2463–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakagawa T, Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Kitamura T, Kakizoe T, Hirohashi S. DNA hypermethylation on multiple CpG islands associated with increased DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 protein expression during multistage urothelial carcinogenesis. J Urol 2005; 173: 1767–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakagawa T, Kanai Y, Ushijima S, Kitamura T, Kakizoe T, Hirohashi S. DNA hypomethylation on pericentromeric satellite regions significantly correlates with loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 9 in urothelial carcinomas. J Urol 2005; 173: 243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kakizoe T, Tobisu K, Takai K, Tanaka Y, Kishi K, Teshima S. Relationship between papillary and nodular transitional cell carcinoma in the human urinary bladder. Cancer Res 1998; 48: 2299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kakizoe T. Development and progression of urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2006; 97: 821–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aleman A, Adrien L, Lopez‐Serra L et al. Identification of DNA hypermethylation of SOX9 in association with bladder cancer progression using CpG microarrays. Br J Cancer 2008; 98: 466–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Estecio MR, Yan PS, Ibrahim AE et al. High‐throughput methylation profiling by MCA coupled to CpG island microarray. Genome Res 2007; 17: 1529–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacinto FV, Ballestar E, Ropero S, Esteller M. Discovery of epigenetically silenced genes by methylated DNA immunoprecipitation in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 11481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nielander I, Bug S, Richter J, Giefing M, Martin‐Subero JI, Siebert R. Combining array‐based approaches for the identification of candidate tumor suppressor loci in mature lymphoid neoplasms. Apmis 2007; 115: 1107–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Misawa A, Inoue J, Sugino Y et al. Methylation‐associated silencing of the nuclear receptor I2 gene in advanced‐type neuroblastomas, identified by bacterial artificial chromosome array‐based methylated CpG island amplification. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 10233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sugino Y, Misawa A, Inoue J et al. Epigenetic silencing of prostaglandin E receptor 2 (PTGER2) is associated with progression of neuroblastomas. Oncogene 2007; 26: 7401–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka K, Imoto I, Inoue J et al. Frequent methylation‐associated silencing of a candidate tumor‐suppressor, CRABP1, in esophageal squamous‐cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2007; 26: 6456–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inazawa J, Inoue J, Imoto I. Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)‐arrays pave the way for identification of novel cancer‐related genes. Cancer Sci 2004; 95: 559–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lopez‐Beltran A, Sauter G, Gasser T et al. Tumours of the urinary system. In: ed. Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. Tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon: IARC Press, 2004; 89–157. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Illingworth R, Kerr A, Desousa D et al. A novel CpG island set identifies tissue‐specific methylation at developmental gene loci. PLoS Biol 2008; 6: e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arai E, Ushijima S, Fujimoto H et al. Genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles in both precancerous conditions and clear cell renal cell carcinomas are correlated with malignant potential and patient outcome. Carcinogenesis 2009; 30: 214–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manabe D, Saika T, Ebara S et al. Comparative study of oncologic outcome of laparoscopic nephroureterectomy and standard nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Urology 2007; 69: 457–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hall MC, Womack S, Sagalowsky AI, Carmody T, Erickstad MD, Roehrborn CG. Prognostic factors, recurrence, and survival in transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: a 30‐year experience in 252 patients. Urology 1998; 52: 594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harris AL, Neal DE. Bladder cancer – field versus clonal origin. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 759–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maruyama R, Toyooka S, Toyooka KO et al. Aberrant promoter methylation profile of bladder cancer and its relationship to clinicopathological features. Cancer Res 2001; 15: 8659–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sathyanarayana UG, Maruyama R, Padar A et al. Molecular detection of noninvasive and invasive bladder tumor tissues and exfoliated cells by aberrant promoter methylation of laminin‐5 encoding genes. Cancer Res 2004; 15: 1425–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Catto JW, Azzouzi AR, Rehman I et al. Promoter hypermethylation is associated with tumor location, stage, and subsequent progression in transitional cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 2903–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yates DR, Rehman I, Abbod MF et al. Promoter hypermethylation identifies progression risk in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 2046–2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim EJ, Kim YJ, Jeong P, Ha YS, Bae SC, Kim WJ. Methylation of the RUNX3 promoter as a potential prognostic marker for bladder tumor. J Urol 2008; 180: 1141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maekita T, Nakazawa K, Mihara M et al. High levels of aberrant DNA methylation in Helicobacter pylori‐infected gastric mucosae and its possible association with gastric cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Frigola J, Song J, Stirzaker C, Hinshelwood RA, Peinado MA, Clark SJ. Epigenetic remodeling in colorectal cancer results in coordinate gene suppression across an entire chromosome band. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 540–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arai E, Ushijima S, Gotoh M et al. Genome‐wide DNA methylation profiles in liver tissue at the precancerous stage and in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2009; (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long‐term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 666–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gallagher DJ, Milowsky MI, Bajorin DF. Advanced bladder cancer: status of first‐line chemotherapy and the search for active agents in the second‐line setting. Cancer 2008; 113: 1284–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lipponen PK. The prognostic value of basement membrane morphology, tumour histology and morphometry in superficial bladder cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1993; 119: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scrimger RA, Murtha AD, Parliament MB et al. Muscle‐invasive transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a population‐based study of patterns of care and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 51: 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Etoh T, Kanai Y, Ushijima S et al. Increased DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) protein expression correlates significantly with poorer tumor differentiation and frequent DNA hypermethylation of multiple CpG islands in gastric cancers. Am J Pathol 2004; 164: 689–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Examples of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA) data validation by pyrosequencing.

Table S1. Eighty‐three bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that were able to discriminate noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) (N) from normal urothelia (C) with a sensitivity and specificity of 75% or more.

Table S2. Twenty bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that were able to discriminate urothelial carcinomas (UCs) in patients who developed recurrence (Pos) from those in patients who did not (Neg).

Table S3. Eleven bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones that were able to discriminate noncancerous urothelia in patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) of the renal pelvis or ureter who developed intravesical metachronous UC (Pos) from those in patients who did not (Neg).

Table S4. Genes, CpG islands in the promoter regions, and repeat elements of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones in Tables S1, S2, and S3.

Table S5. Primer sets for validation study by pyrosequencing.

Table S6. Correlation between smoking history and DNA methylation status in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) and UCs.

Table S7. Correlation between protein expression levels of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 and DNA methylation status in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) and UCs.

Table S8. Correlation between regional DNA hypermethylation on CpG islands and the results of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array‐based methylated CpG island amplification (BAMCA) in noncancerous urothelia obtained from patients with urothelial carcinomas (UCs) and UCs.

Please note: Wiley‐Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Supporting info item

Supporting info item