Using noise to probe and characterize gene circuits

Abstract

Stochastic fluctuations (or “noise”) in the single-cell populations of molecular species are shaped by the structure and biokinetic rates of the underlying gene circuit. The structure of the noise is summarized by its autocorrelation function. In this article, we introduce the noise regulatory vector as a generalized framework for making inferences concerning the structure and biokinetic rates of a gene circuit from its noise autocorrelation function. Although most previous studies have focused primarily on the magnitude component of the noise (given by the zero-lag autocorrelation function), our approach also considers the correlation component, which encodes additional information concerning the circuit. Theoretical analyses and simulations of various gene circuits show that the noise regulatory vector is characteristic of the composition of the circuit. Although a particular noise regulatory vector does not map uniquely to a single underlying circuit, it does suggest possible candidate circuits, while excluding others, thereby demonstrating the probative value of noise in gene circuit analysis.

Keywords: gene circuit analysis, noise analysis, stochastic gene expression

The emerging field of noise biology focuses on the sources, processing, and biological consequences of the inherent stochastic fluctuations in the populations, concentrations, positions, or states of molecules that control cellular function and behavior (1–22). Most of these studies have been directed toward the question: what are the noise characteristics that emerge from a particular well defined gene circuit? An intriguing prospect emerges when the question is turned around: to what extent can measured noise characteristics provide information regarding the underlying gene circuit? A few examples of this type of inference have been published. In two recent flow cytometry studies of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2, 14), the observed relationship between noise and protein expression level was interpreted to be consistent with a predominance of intrinsic noise originating from fluctuations in mRNA levels. Another study (17) inferred that protein mixing times (the time scale required for the protein level in a single cell to transition from higher than the population average to lower than the population average) exceeding one cell generation could originate from upstream noise sources or the presence of feedback loops. In this article, we develop a generalized framework for probing the circuit of a particular gene via its intrinsic noise.

The noise behavior of a given gene circuit is given by:

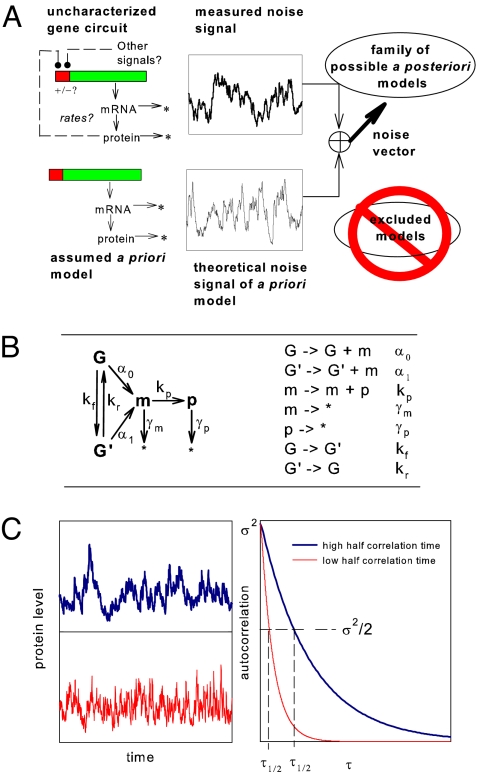

where N⃗ is the noise structure vector (defined below), m is a model of the system comprised of circuit structure (S; architecture or regulatory arrangements) and circuit rate parameters (k; e.g., kinetic rates), and g is an analysis or simulation operation that reveals the noise structure of the model. Eq. 1 states that the noise structure is uniquely determined by circuit structure and parameters. Here, we seek to find another function, ĝ, such that m(S, k) = ĝ(N⃗); that is, we wish to determine the architecture and kinetic rates from a circuit's noise structure. In general terms, our method is based on a comparison of the measured noise structure of the circuit of interest to the theoretical noise structure of an assumed model (Fig. 1A). In this article, we describe the process by which these two signals are processed to yield the noise regulatory vector that points toward a family of possible circuits consistent with the measured signal and away from other possible circuits that are incompatible with the measured signal (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Noise regulatory vector and its application in the analysis of gene circuits. (A) The noise regulatory vector for an uncharacterized gene circuit is determined by comparison of its experimental noise structure to the noise structure of an assumed model. The vector points toward a family of gene circuits that includes the true gene circuit, and away from inappropriate models. (B) The assumed structure of the a priori model is a constitutive transcription-translation circuit. (C) Time series and autocorrelation functions for two stochastic protein populations characterized by identical 〈p〉 and CV2 but different half correlation times τ1/2.

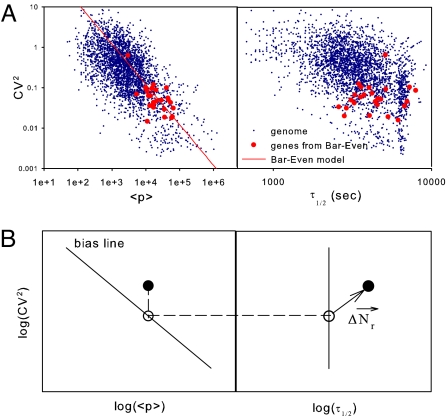

The noise regulatory vector ΔN⃗r is defined as:

where N⃗m is the measured noise structure vector for the circuit of interest, and N⃗A is the theoretical noise structure vector for the assumed a priori circuit model m(SA, kA). The assumed structure SA is based on a priori knowledge of the circuit, which may not be complete. Through experimental observations Ω, we can select parameters kA, such that the model m(SA, kA) maps onto the observations f(m(SA, kA))⇒Ω, where f is a solution of the model that can be compared with Ω.

This framework is general, in that it may be adapted to any a priori circuit structure SA, appropriate experimental observables Ω, and defined noise structure vector N⃗. For example, in practice, one may specify the a priori circuit to include everything known about a particular gene circuit. In this work, we assume SA to be a constitutive transcription-translation circuit [Fig. 1b, supporting information (SI) Text, and Table S1]. This definition is appropriate in the case where little is known about the gene-specific regulatory mechanisms on which SA is defined. Furthermore, it allows kA to be uniquely defined from Ω consisting of only abundance and stability of mRNA and protein molecules (see Methods).

The complete noise structure of a molecular population or concentration [M(t)] is contained in the autocorrelation function [ACF, Φ(τ)], which is defined as

where 〈M(t)〉 is the average value of M(t), and E· returns the expected value of the term within the bracket. In an ideal case, ΔN⃗ would be the difference between measured and a priori ACFs, but in practice, there are experimental constraints that limit the accuracy of measured ACFs. The accuracy of the ACF, particularly at larger values of τ, is compromised by the limited number of cells tracked and the limited duration of observation in time-lapse fluorescence microscopy (1, 22). Here, we will consider a noise structure N⃗ represented by two components: (i) noise magnitude, which is a measure of the size of fluctuations; and (ii) noise correlation (or frequency content), which is an indication of the dynamic responsiveness of the protein level to changes in the environmental or physiological state of the cell. The relationship between Φ(τ) and the components of N⃗ is shown in Fig. 1C. The noise magnitude is quantified by Φ(0), which is the noise variance σ2 and is often normalized by the square of the mean to give CV2 = Φ(0)/〈M(t)〉2, where CV is known as the coefficient of variation. We quantify correlation using the half correlation time (τ1/2), which is defined by Φ(τ1/2) = Φ(0)/2; that is, τ1/2 defines the time for correlation to fall to ½ of its original value. With these two components, we choose to define the noise structure and regulatory vectors in this work as (see SI Text):

where m̂ and ĉ are log-scale unit vectors on the magnitude and correlation axes, respectively, and subscripts m and A denote measured and assumed quantities, respectively. The noise vectors are defined in log-space to capture the natural scaling of noise in biological systems. To interpret ΔN⃗r, we compare it to a catalog of theoretical regulatory vectors ΔN⃗rT = g(m(S, k)) for models over a wide range of S and k, to suggest one or more a posteriori models m(SP, kP) to better capture the true nature of the gene circuit. In this way, the noise regulatory vector “points” toward a family of possible a posteriori models that includes the true gene circuit and away from inappropriate models. In the remainder of this article, we illustrate the probative value of noise in gene circuit analysis by expanding on the conceptual rationale for the above framework and developing the theoretical noise regulatory vectors for several common regulatory motifs.

Results

A priori Noise Vectors.

We now present an expanded development of the noise regulatory vector, beginning with the definition of the noise vector N⃗A for the a priori model m(SA,kA). We illustrate the definition of m(SA,kA) by assuming a simple transcription-translation circuit (SA) and using it to interpret experimental observables (Ω) consisting of a compilation of several genome-scale databases characterizing the abundance and stability of mRNA and proteins in S. cerevisiae (see Methods). Our model of the intrinsic noise of protein synthesis is based on a system of first-order reactions (Fig. 1B; details provided in SI Text and Table S1). We further assume that gene activation kinetics are fast (kf + kr ≫ α0,γm,γp), and that α1 = 0. Under these assumptions, the remaining parameters kA may be obtained directly from Ω (see Methods).

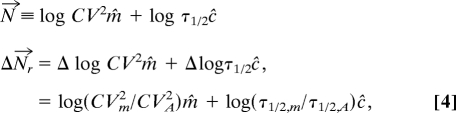

We define noise vectors in the context of a 3D plot of the two noise component axes CV2 and τ1/2 and a mean protein axis 〈p〉, which we term the 3D noise map. Two orthogonal planes of the 3D noise map for S. cerevisiae are shown in Fig. 2A, which should be considered an illustrative example due to limitations in the compiled database (see Methods). Each point in the noise map in Fig. 2A represents the noise characteristics of a particular protein. However, through the action of the regulatory mechanism, the expression level of the gene is likely to change in response to physiological or environmental conditions. The manner in which the noise characteristics change with changing expression level of the gene contains information about the underlying regulatory motif. Bar Even et al. (2) and Newman et al. (14) interpreted the CV2 ∝ 1/〈p〉 scaling observed in their studies, present in our database-derived noise map (Fig. 2A), to be consistent with a predominance of intrinsic noise originating from fluctuations in mRNA levels and a relatively low contribution of extrinsic noise at low and moderate values of 〈p〉. However, the ability to infer regulatory mechanisms from noise characteristics may be enabled by consideration of the τ1/2 component of the noise, which has been ignored in most gene noise investigations to date. For example, analysis of Eqs. 4 and 8 indicates that modulation of 〈p〉 via changes in protein stability also yields the observed CV2 ∝ 1/〈p〉 relationship, under conditions where protein stability is much greater than mRNA stability (γm ≫ γp). It is impossible to distinguish between the two mechanisms of protein modulation based on the CV2 vs. 〈p〉 view alone. However, as we show below, the two mechanisms can easily be distinguished when both the CV2 and τ1/2 components of noise are considered together, because the latter component is affected by changes in protein stability but not by changes in transcription rate. In fact, the distribution of τ1/2 values observed in Fig. 2B suggests that variability in protein stability may have contributed to the observed pattern of CV2 ∝ 1/〈p〉 scaling.

Fig. 2.

Relationship of 3D noise map and noise regulatory vectors, ΔN⃗r. (A) Noise map for 2,920 ORFs in S. cerevisiae. A subset of 25 proteins that were both included in the Bar-Even et al. (2) study and present in our compiled database (shown in red) are observed to scatter about the Bar-Even (2) noise model CV2 = 1,200/〈(p〉 (red line), suggesting a similarity in measured noise trends [Bar-Even (2)] and those inferred from literature data (blue points). (B) Graphical definition of the bias line and ΔN⃗r. The bias line represents the behavior of the a priori model. To determine N⃗Δr for a protein with measured coordinates on the noise map (filled circle), one first locates the bias point (open circle) by projecting vertically to the bias line. ΔN⃗r is defined by the 2D vector connecting the bias point to the measured point in the log(CV2)−log(τ1/2) plane.

We incorporate the CV2 ∝ 1/〈p〉 scaling in our a priori model by stipulating that modulation of 〈p〉 is achieved through variation of the effective transcription rate. With these assumptions, the noise vector of the a priori model is given by:

where c1 and c2 are protein-specific constants (see Eq. 7 in SI Text), which are functions of Ω measured under standard (defined) physiological and environmental conditions. Experimental techniques for measuring the mRNA and protein abundances and half-lives are reviewed in the SI Text. The line defined by the locus of all N⃗A over all values of 〈p〉 is termed the bias line (see Fig. 2B). In the case of our a priori model, the bias line represents the hypothetical intrinsic noise characteristics of the gene under the assumption that its activity is regulated by rapid, noise-free modulation of the effective transcription rate. The bias line is hypothetical, because the actual regulatory mechanism of the gene may be quite different from the a priori model. The bias line is a reference state from which we quantify deviations in noise characteristics attributable to alternative regulatory mechanisms, such as modulation of translation rate, modification of protein, or mRNA stability, slow or noisy modulation of transcription, or positive or negative feedback.

Graphically, the noise regulatory vector ΔN⃗r is defined as the vector in the log(CV2) vs. log(τ1/2) plane (i.e., ΔN⃗r as defined here is 2D), which quantifies the deviation of the measured noise characteristics from the bias line at the measured value of 〈p〉 (Fig. 2B, see SI Text Eq. 8 for analytical description). Measurements of 〈p〉, CV2, and τ1/2 are made using time-lapse microscopy (1, 5, 15, 22, 23). These measurements need not be made under the same experimental conditions used to define the bias line, because the goal is to make inferences of the underlying regulatory mechanism as it responds to changes in physiological and environmental conditions. We now develop theoretical noise regulatory vectors ΔN⃗rT for several common regulatory mechanisms.

Fast Operator Kinetics.

We first analyze the simple transcription-translation model shown in Fig. 1B for the case where the operator kinetics are fast. This model is identical to the a priori model, except we relax the assumption that changes in 〈p〉 are modulated only by variation of km,eff and consider also changes in kp, γm, and γp. We first consider the case in which mRNA is more stable than proteins (γm/γp ≫ 1) and high translational efficiency (b ≫ 1), which is applicable to many prokaryotic and some eukaryotic proteins. Under these conditions, changes in kp and γm can be considered in the context of the resulting change in b. The magnitudes of the components of ΔN⃗rT for changes in these parameters (Table 1) are derived via analysis of Eqs. 4 and 8 (see Methods and SI Text). In general, modulation of 〈p〉 by changing translation efficiency affects the noise magnitude, whereas modulation of 〈p〉 by changing protein stability affects the dynamic responsiveness, compared with modulation of 〈p〉 by changes in transcription rate. These patterns are reflected in ΔN⃗r and allow the inference of possible mechanisms of protein modulation and the magnitude of the parameter changes. These inferences allow certain regulatory mechanisms to be excluded and allow additional characterization to be focused on the most likely candidate models. The effects of simultaneous variation of more than one parameter can be predicted by simple addition of the independent vector components.

Table 1.

Components of Δ N⃗rT for transcription-translation model with fast regulatory kinetics and b >> 1

| 〈p〉 modulated by | Δlog CV2 | Δlog τ1/2 |

|---|---|---|

| Δkm,eff | 0 | 0 |

| Δb (γm/γp >>1) | Δlog(b) | 0 |

| Δγp (γm/γp >>1) | 0 | −Δlog(γp) |

| Δb (γm/γp approaches 1) | Δlog(b) −χm,Δb | χc,Δb |

| Δγp (γm/γp approaches 1) | −χm,Δγ | −Δlog(γp) + χc,Δγ |

For many of the proteins in our combined yeast database, the time scale of mRNA decay is of the same order as the cell-doubling time, in which case γm/γp could approach unity. Numerical analysis of Eqs. 4 and 8 revealed that relaxing the assumption γm/γp ≫ 1 necessitates small corrections to the ideal vectors (Table 1, see SI Text and Fig. S1).

Slow Operator Kinetics.

When the time scale of operator transitions approaches or exceeds the time scale of transcription and decay processes, operator dynamics add significant noise to the system (3, 11, 19). Long time scales in operator transitions can originate from many different underlying biological mechanisms, such as cell-cycle-dependent gene expression, low frequency noise in activators and repressors, or chromatin remodeling. These systems must be analyzed with care (see SI Text and Figs. S2 and S3).

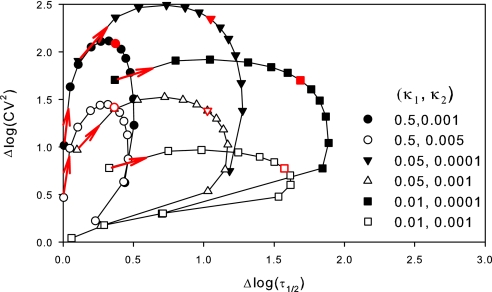

Noise map coordinates for systems characterized by slow operator dynamics are calculated analytically under the assumption γm/γp ≫ 1 (see Eq. 5, SI Text). As expected, all of the noise vectors reside in the upper-right quadrant of the Δlog(CV2)−Δlog(τ1/2) plane (Fig. 3), because slow operator dynamics adds noise and slows the dynamics of the system. The mean gene activity level G(t) is determined by kr/(kr + kf). Deviations from bias-line behavior are largest at moderate levels of gene activity and disappear as G(t) approaches 0 and 1, consistent with earlier work (3, 19). We now define two ratios that characterize the DNA-binding kinetics: κ1 = kr/γp and κ2 = (kr/α0). In general, κ1 has a larger effect on the direction of the vectors, whereas κ2 has a larger effect on the overall magnitude of the vectors. At κ1 ≫ 1, only the Δlog(CV2) component of the noise vector is significant, because 1/γp is the dominant time scale under both bias-line and experimental conditions. However, as κ1 decreases below 1, the operator dynamics control the time scale of protein fluctuations, and the Δlog(CV2) component becomes increasingly significant. The overall magnitude of the deviation is negligible for κ2 ≥ 1 and increases as κ2 decreases below 1. This can be most easily understood by realizing that small values of κ2 are associated with small values of b (κ2 = κ1γp/α0 = κ1b/〈p〉0, where 〈p〉0 is the mean protein level in the absence of regulation = α0b/γp), which in turn results in a decrease in CVA2 relative to large κ2 and hence an increase in Δlog(CV2). In other words, systems with large b are inherently noisy; therefore, the additional noise attributable to slow operator dynamics is smaller relative to the bias line circuit. The distortion of the bottom of some of the curves in Fig. 3 is an artifact related to the operational definition of τ1/2 (see SI Text and Fig. S3).

Fig. 3.

Noise regulatory vectors for the gene circuit in Fig. 1B as affected by slow operator kinetics. Points indicate ΔN⃗rT for G(t) values of (starting from and moving in the direction of the red arrow) 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 (red), 0.6, 0.7. 0.8, 0.9, 0.95, and 0.99. The effect of operator kinetics is captured in the ratios κ1 = kr/γp and κ2 = kr/α0.

Autoregulation.

So far, we have demonstrated that parameter deviations from the a priori model m(SA, kA) are quantitatively captured in ΔN⃗r. We now use stochastic simulation (6, 12) of negatively and positively regulated gene circuits (see models in SI Text and Table S1) to quantify how these specific deviations of model structure S relative to the a priori model are reflected in ΔN⃗r. Negative autoregulation is a mechanism of maintaining homeostatic protein levels that is reported to decrease both CV2 (20, 24) and τ1/2 (1, 18).

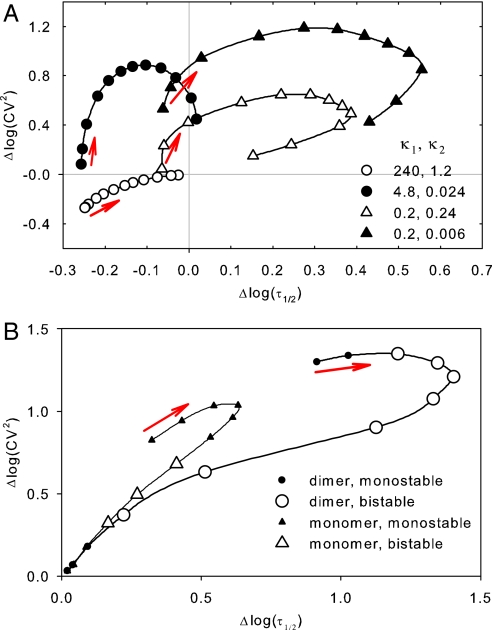

The noise behavior of negatively autoregulated gene circuits strongly depends on the speed of the operator kinetics, which we found to be conveniently characterized by kinetic ratios analogous to those defined in the previous section (κ1 = kar/γp and κ2 = kar/α0, , where kar is the rate constant for dissociation of the autoregulator–DNA complex). Specification of κ1 and κ2 also fixes the ratio b/〈p〉0 and results in noise vectors that are independent of 〈p〉0. Classical negative autoregulation behavior (a decrease in both CV2 and τ1/2) occurs as both κ1 and κ2 approach unity, in which case the operator dynamics may be considered to be fast (Fig. 4A). For a given value of G(t), the regulation vectors are observed to rotate clockwise and grow larger in magnitude with decreasing κ1 and κ2 as the DNA-binding kinetics become slower (Fig. 4A). For the case of κ1 ≥ 1, the predominant effect of decreasing κ2 below a value of one is to increase Δlog(CV2) (Fig. 4A). However, for κ1 < 1, a decrease in κ2 causes both Δlog(CV2) and Δlog(τ1/2) to increase, effectively increasing the magnitude of the vector (Fig. 4A). Therefore, when κ1 and κ2 are both <1, the former can be considered to primarily change the direction of the noise vector, whereas the latter primarily controls its magnitude, as was the case for the nonautoregulated vectors considered in the previous section. Overall, negative autoregulation may result in either an increase or a decrease in CV2 and τ1/2, depending on whether the repression kinetics are fast or slow. This likely explains a few reports in the literature in which negative autoregulation appears to either have little effect on noise or even increases it (e.g., ref. 9).

Fig. 4.

Noise regulatory vectors for autoregulation. Points indicate ΔN⃗rT at gene activation levels of (starting from and moving in the direction of the red arrow) 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7. 0.8, 0.9, and 0.95. (A) Negative autoregulation. The effect of decreasing κ2 is to increase Δlog(τ1/2) when κ1 1 and to increase both Δlog(CV2) and Δlog(τ1/2) when κ1 < 1. (B) Positive autoregulation. The effect of multimerization and regimes of mono- and bistability.

Because the role of negative autoregulation is thought to be to reduce the magnitude and correlation components of noise (1, 18, 20, 24), we sought to identify conditions in which these effects were enhanced. First, we recognized that lower values of b correspond to stronger effects of negative autoregulation at high levels of repression (see SI Text and Fig. S4). At high repression, transcription events are relatively rare; however, when b is high, a large number of proteins are translated from each transcription event. These proteins persist until they are removed by decay or dilution. The feedback system is no longer able to tightly regulate the protein level around 〈p〉, rather the instantaneous value of protein level varies widely from near zero to around b, with small values of 〈p〉 being achieved by shutting down transcription for long periods of time. The noise dynamics of the system then becomes controlled by protein decay/dilution rather than by feedback in strongly repressed systems with high b.

We also considered the case in which the autorepressor must first form a multimer before binding to the operator and the case of cooperative binding of multiple monomers to operator sites. Repression by multimers and cooperative binding were shown to have similar effects when the kinetics of complex formation were sufficiently rapid (SI Text and Fig. S5). Compared with regulation with the monomer, regulation by a dimer results in a small additional decrease in Δlog(CV2) and Δlog(τ1/2) when the operator kinetics are fast (Fig. S4).

A positively autoregulated gene circuit is characterized by a low basal state and a high induced state. The system is schematically identical to the negative autoregulation case except now G and G′ are the basal (transcription rate α0) and induced (transcription rate α1) states of the gene, respectively. Depending on the parameter regime, the circuit may be monostable only in the high or the low state, or it may possess bistability in which both the high and low states are stable (10, 16, 25). Noise regulatory vectors for a wide range of parameters were generated by using stochastic simulation. Both the CV2 and τ1/2 components of ΔN⃗rT are positive over the entire parameter space, consistent with previously known characteristics of the system (16, 25). Unlike negative autoregulation, the noise regulatory vectors for positive autoregulation are strongly affected by multimerization (Fig. 4B). In the absence of other nonlinearities (e.g., population-dependent protein degradation), deterministic analysis predicts that autoregulation by a monomer is always monostable (25), whereas higher multimers can introduce bistability. Points characterized by bistability (as determined by histograms of the simulation results) are shown as open symbols. It is noteworthy that, in a stochastic context, autoregulation by the monomer was able to generate bistability. Stochastic bistability occurs when the positive-feedback effect is strong enough to sustain an induced state, but stochastically it is possible for the protein concentration to decay to zero. Nevertheless, the deterministically bistable dimer system is characterized by bistability over a much greater range of average induction levels G′ (Fig. 4B). The sensitivity of ΔN⃗rT to other parameter values in positively regulated gene circuits is provided in SI Text and Fig. S6.

Discussion

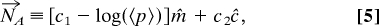

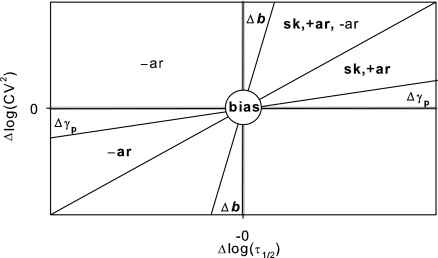

The noise regulatory vector ΔN⃗r is a framework for interpreting measurements of gene noise to determine the fidelity of an assumed gene circuit model. Unlike conventional goodness-of-fit tests, ΔN⃗r can suggest necessary modifications of the parameter values k and/or structure S of the assumed model to better represent the noise behavior of the circuit. These suggestions arise from comparison of experimentally measured ΔN⃗r to a catalog of theoretical noise regulatory vectors ΔN⃗rT = g(m(S, k)) representing many different models. The “first edition” of such a catalog is given in Fig. 5, which summarizes the mapping of ΔN⃗rT for the regulatory motifs considered in this work to various spatial domains in the log(τ1/2)−log (CV2) plane. Additional motifs can be added as they are developed. Interestingly, there are some domains in which multiple motifs are operative, whereas others cannot be reached by any one of the motifs analyzed here, acting alone. Although the domains are not unique to a single regulatory motif, it allows additional experimental characterization to focus on the most likely candidates. Although the direction of ΔN⃗r points to one or more motifs, its magnitude provides information that constrains the range of viable biokinetic parameters.

Fig. 5.

Summary of noise vector domains for various regulatory motifs. (−ar, negative autoregulation; +ar, positive autoregulation; sk, slow gene activation kinetics). Bold font denotes domains of primary influence.

The noise vectors may be particularly useful when they are measured over a wide range of experimental conditions to assess specific contexts in which different regulatory motifs may be operative. In this case, the workflow in Fig. 1 may be used in an iterative manner in which the a posteriori gene circuit of one iteration becomes the a priori circuit for the next.

Noise regulatory vectors could be easily applied to a number of experimental studies in the recent literature. For example, recent studies have sought to build predictable gene circuits with complex feedback (7) or combinatorial promoters with multiple repressor-binding sites (13) based on understanding obtained by studying their simpler subcomponents. In this case, the a priori model would be based on the characterized components. A noise regulatory vector close to zero would result if the composed system performed as predicted. This is a particularly stringent test because the noise regulatory vector depends on both CV2 and τ1/2. Deviations would result in noise vectors that, when compared with an appropriately constructed catalog of theoretical noise vectors, would point toward modifications of the model needed to capture system behavior.

In this work, we have considered noise vectors with CV2 and τ1/2 components. One interesting extension of the method is the use of higher-dimensional noise vectors. Additional dimensions may be able to better capture nuances in the shape of the autocorrelation function that correlate strongly to particular regulatory motifs. It may also be possible to include cross-correlation components to the noise vector that indicate regulatory relationships between two genes within the same circuit.

One final interesting observation concerns the relative magnitude of b in eukaryotes (b up to 1,000 or more; ref. 2). and our compiled database) vs. prokaryotes [typically <100 (20)]. The noise effects (relative to the bias circuit) of slow operator kinetics and positive and negative autoregulation were shown to be amplified when b is small. It appears that negative autoregulation, a common regulatory that is beneficial in reducing the effects of noise, has coevolved with relatively small values of b in prokaryotes. Conversely, regulatory processes that increase noise such as chromatin remodeling, cell-cycle-dependent gene regulation, and positive autoregulation seem to have coevolved with more efficient translation systems (high b) in eukaryotes. In the latter case, the evolution of noise-tolerant cell function would perhaps accommodate both noisy regulatory processes and noisy constitutive gene expression associated with efficient translation.

Methods

Construction of 3D Noise Map.

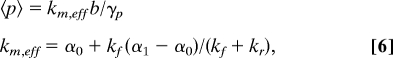

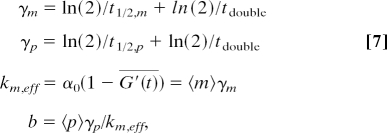

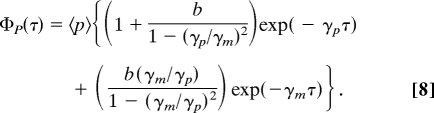

As an illustrative example, we used our assumed transcription-translation circuit (SA) to interpret experimental observables (Ω) consisting of a compilation of several genome-scale databases characterizing the abundance and stability of mRNA and proteins in S. cerevisiae. We combined separate databases for mRNA abundance 〈m〉 (26), mRNA half-life (t1/2,m) (27), protein abundances 〈p〉 (28), and protein half-life (t1/2,p) (29) by matching data across ORFs. Because the measurements in the compiled database were made by different researchers at different times under different experimental conditions, caution should be used in their use. Our model of the intrinsic noise of protein synthesis is based on a system of first-order reactions (Fig. 1B; details provided in SI Text and Table S1). As part of our definition of m(SA,kA), we assume that gene activation kinetics are fast (kf + kr ≫ α0,γm,γp), and that α1 = 0. Under these conditions, the steady-state mean protein level 〈p〉 is given by:

where km,eff is the effective transcription rate, and b = kp/γm is the average number of proteins synthesized per transcript. Values of CV2 (= ΦP(0)/〈p〉2) and τ1/2 (ΦP(τ1/2) = ΦP(0)/2) were calculated from the autocorrelation function of protein level [Φp(τ); see Eq. 8] for each of the 2,920 ORFs in the combined database (Dataset S1).

Relationship of Parameters kA to Observables Ω.

The values of model parameters kA are assumed to be related to Ω according to:

under the assumptions α1 = 0 and tdouble = 90 min in yeast.

Calculation of Autocorrelation Functions.

Under conditions in which gene activation kinetics are fast (kf + kr ≫ α0,γm,γp), and extrinsic noise is negligible (2), the protein autocorrelation function Φp(τ) for model structure SA (shown in Fig. 1B and SI Text and Table S1) is given by:

The analytical expression for Φp(τ) in the case where gene activation kinetics are slow, from which Eq. 8 is derived, is given by Eq. 5 in SI Text.

Stochastic Simulation and Construction of Noise Maps.

Exact stochastic simulations of negative and positive autoregulation models were performed by using the Sorting Direct Method (12), an optimized version of Gillespie's original Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (6). Values of CV2 and τ1/2 were determined from the autocorrelation function, which was calculated by Eq. 3. Parameter values were swept to generate 3D noise maps. Noise regulatory vectors were constructed by cubic spline interpolation of the 3D maps, after smoothing with a running average function (n = 5).

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments.

We thank Natalie Ostroff for thoughtful review of the manuscript. R.D.D., M.S.A., and M.L.S. acknowledge support from the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences, which is sponsored by Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, U. S. Department of Energy. J.M.M. acknowledges the use of Miami University's 128 node Redhawk Computing Cluster, which was used for the stochastic simulations.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Austin DW, et al. Gene network shaping of inherent noise spectra. Nature. 2006;439:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature04194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-Even A, et al. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat Genet. 2006;38:636–643. doi: 10.1038/ng1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake WJ, Kaern M, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Noise in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature. 2003;422:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature01546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox CD, et al. Frequency domain analysis of noise in simple gene circuits. Chaos. 2006:16. doi: 10.1063/1.2204354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science. 2002;297:1183–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillespie DT. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical-reactions. J Phys Chem. 1977;81:2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guido NJ, et al. A bottom-up approach to gene regulation. Nature. 2006;439:856–860. doi: 10.1038/nature04473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasty J, McMillen D, Isaacs F, Collins JJ. Computational studies of gene regulatory networks: In numero molecular biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:268–279. doi: 10.1038/35066056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooshangi S, Weiss R. The effect of negative feedback on noise propagation in transcriptional gene networks. Chaos. 2006:16. doi: 10.1063/1.2208927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaacs FJ, Hasty J, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Prediction and measurement of an autoregulatory genetic module. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7714–7719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332628100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kepler TB, Elston TC. Stochasticity in transcriptional regulation: Origins, consequences, and mathematical representations. Biophys J. 2001;81:3116–3136. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75949-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCollum JM, Peterson GD, Cox CD, Simpson ML, Samatova NF. The sorting direct method for stochastic simulation of biochemical systems with varying reaction execution behavior. Comput Biol Chem. 2006;30:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy KF, Balazsi G, Collins JJ. Combinatorial promoter design for engineering noisy gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12726–12731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608451104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman JRS, et al. Single-cell proteomic analysis of S-cerevisiae reveals the architecture of biological noise. Nature. 2006;441:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature04785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenfeld N, Young JW, Alon U, Swain PS, Elowitz MB. Gene regulation at the single-cell level. Science. 2005;307:1962–1965. doi: 10.1126/science.1106914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott M, Hwa T, Ingalls B. Deterministic characterization of stochastic genetic circuits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7402–7407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610468104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sigal A, et al. Variability and memory of protein levels in human cells. Nature. 2006;444:643–646. doi: 10.1038/nature05316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson ML, Cox CD, Sayler GS. Frequency domain analysis of noise in autoregulated gene circuits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4551–4556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0736140100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson ML, Cox CD, Sayler GS. Frequency domain chemical Langevin analysis of stochasticity in gene transcriptional regulation. J Theor Biol. 2004;229:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thattai M, van Oudenaarden A. Intrinsic noise in gene regulatory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8614–8619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151588598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volfson D, et al. Origins of extrinsic variability in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature. 2006;439:861–864. doi: 10.1038/nature04281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinberger LS, Dar RD, Simpson ML. Transient-mediated fate determination in a transcriptional circuit of HIV. Nat Genet. 2008;40:466–470. doi: 10.1038/ng.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Megason SG, Fraser SE. Imaging in systems biology. Cell. 2007;130:784–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becskei A, Serrano L. Engineering stability in gene networks by autoregulation. Nature. 2000;405:590–593. doi: 10.1038/35014651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becskei A, Seraphin B, Serrano L. Positive feedback in eukaryotic gene networks: Cell differentiation by graded to binary response conversion. EMBO J. 2001;20:2528–2535. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arava Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA translation profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3889–3894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0635171100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang YL, et al. Precision and functional specificity in mRNA decay. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5860–5865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092538799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425:737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belle A, Tanay A, Bitincka L, Shamir R, O'Shea EK. Quantification of protein half-lives in the budding yeast proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13004–13009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605420103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information