Development of a lung cancer therapeutic based on the tumor suppressor microRNA-34

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2011 Jul 15.

Abstract

Tumor suppressor microRNAs (miRNAs) provide a new opportunity to treat cancer. This approach, “miRNA replacement therapy”, is based on the concept that the re-introduction of miRNAs depleted in cancer cells reactivates cellular pathways that drive a therapeutic response. Here, we describe the development of a therapeutic formulation using chemically synthesized miR-34a and a lipid-based delivery vehicle that blocks tumor growth in mouse models of non-small cell lung cancer. This formulation is effective when administered locally or systemically. The anti-oncogenic effects are accompanied by an accumulation of miR-34a in the tumor tissue and downregulation of direct miR-34a targets. Intravenous delivery of formulated miR-34a does not induce an elevation of cytokines or liver and kidney enzymes in serum, suggesting that the formulation is well tolerated and does not induce an immune response. The data provide proof of concept for the systemic delivery of a synthetic tumor suppressor mimic, obviating obstacles associated with viral-based miRNA delivery and facilitating a rapid route for miRNA replacement therapy to the clinic.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding, naturally occurring RNA molecules that post-transcriptionally modulate gene expression and determine cell fate by regulating multiple gene products and cellular pathways (1). The misregulation of miRNAs is often a dire cellular event that can contribute to the development of human disease including cancer (2, 3). miRNAs deregulated in cancer target multiple oncogenic signaling pathways and have therefore the potential of becoming powerful therapeutic agents (4, 5). Among the miRNAs expressed at reduced levels in various human cancer types is miR-34a (6–11). miR-34a is a member of the miR-34 family, that comprises miR-34a, miR-34b and miR-34c. The miR-34a gene is located on chromosome 1p36.22 in a region that has previously been associated with various cancers including lung cancer (12). In addition, frequent hypermethylation of the miR-34a promoter is another mechanism that can lead to reduced miR-34a expression in lung cancer and other cancer types (7, 11). miR-34a is transcriptionally induced by the tumor suppressor p53 (6, 13–16) and low miR-34a expression levels correlate with a high probability of relapse in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (11). Overexpression of miR-34a inhibits the growth of cultured cancer cells and affects gene products that promote cell cycle progression and counteract apoptosis (6, 13–16). miR-34a also inhibits the growth of pancreatic cancer stem cells (17). Thus, miR-34a displays an anti-proliferative phenotype in numerous cancer cell types (6, 13–16). However, the anti-oncogenic activity in vivo and its potential as a therapeutic remains unknown. Here, we demonstrate the tumor suppressor function of miR-34a in vivo and evaluate the therapeutic activity of a synthetic miR-34a mimic in an effort to restore a loss of function in cancer.

Materials and Methods

Human tissue samples, cell lines and oligos

13 flash-frozen NSCLC tumor samples and corresponding normal adjacent tissues were purchased from ProteoGenex (Culver City, CA); 5 flash-frozen tissue pairs were purchased from the National Disease Research Interchange (Philadelphia, PA). All 14 FFPE lung tumor samples and normal adjacent tissues were acquired from Phylogeny/Folio Biosciences (Columbus, OH). All lung cancer cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured according to vendor's instructions: A549, BJ, NCI-H460, Calu-3, NCI-H596, NCI-H1650, HCC2935, SW-900, NCI-H226, NCI-H522, NCI-H1299, Wi-38 and TE353.sk. Primary T cells were obtained from Atlanta Pharmaceuticals. Transfection and proliferation assays were carried out as described (18, 19), and proliferation was assessed using AlamarBlue™ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) 3–7 d post transfection depending on the growth rates of individual cell lines. Cellular viability was determined using Neutral Red from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) following the manufacturer's instructions. For colony formation assays, 5 × 106 cells were electroporated with 1.6 μM miRNA in 200 μl OptiMEM (Invitrogen) using the BioRad GenePulserXcell™ instrument, and 3000 cells were seeded on 100-mm dishes. After 32 days, colonies were stained with 2% crystal violet and colonies containing >50 cells were counted. Synthetic miRNAs and siRNAs were obtained from Ambion, Applied Biosystems (cat. nos. AM17100 and AM4639; Austin, TX) and Dharmacon, Thermo Scientific (Boulder, CO).

qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from flash-frozen non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumors and normal adjacent tissues, as well as human lung cancer cells and tumor xenografts was isolated using the mirVANA PARIS RNA isolation kit (cat. no. AM1556, Ambion, Austin, TX) following the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues was isolated using the RecoverAll Kit from Ambion (cat. no. AM1975). For qRT-PCR detection of the miR-34a oligonucleotide, 10 ng of total RNA and miR-34a-specific RT-primers (Assay ID 000426 TaqMan miRNA Assay, Applied Biosystems (ABI), Foster City, CA) were heat-denatured at 70 °C for 2 min and reverse-transcribed using MMLV reverse transcriptase (cat. no. 28025-021, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The house-keeping miRNAs miR-191 and miR-103 (ABI Assay IDs 002299 and 000439) were amplified as internal references (20) to adjust for well-to-well RNA input variances. For detection of mouse IFIT1 mRNA levels in mouse lung tissue, cDNA was generated by random decamers (AM5722G, Ambion, Austin, TX) using 10 ng of total RNA at conditions described above and amplified using a TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (ABI Assay ID Mm00515153_m1). Raw CT values were normalized to the ones of murine GAPDH (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) to correct for equal input of RNA. For detection of human TP53, p21WAF1/CIP1 and MDM2 in NSCLC tissues, cDNA was generated by random decamers using 500 ng of total RNA at conditions described above and amplified using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays Hs99999147_m1 (TP53), Hs00355782_m1 (p21) and Hs99999008_m1 (MDM2). Raw Ct values were normalized to a geometric mean of PPIA (amplified using ABI Assay Hs99999904_m1), GAPDH (amplified using ABI assay Hs99999905_m1), and 18S (amplified using ABI assay Hs99999901_s1). All gene expression levels were determined by real-time PCR using Platinum Taq Polymerase reagents (Invitrogen) and the ABI Prism 7900 SDS instrument (Applied Biosystems).

Lung cancer xenografts

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with current prescribed guidelines and under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at BIOO Scientific Corporation (Austin, TX). H460 and A549 NSCLC cells were collected, counted and mixed with matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) in a 1:1 ratio by volume. 3 × 106 cells in 100 ul of media/matrigel solution were injected subcutaneously in the lower back region of female NOD/SCID mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Tumor volumes were determined as previously described (18). One hundred or twenty μg miRNA was formulated with MaxSuppressor in vivo RNALancerII, a lipid based delivery reagent (BIOO Scientific, Inc., Austin, TX), according to manufacturer's instructions. Formulated miRNA was administered intratumorally or intravenously by tail vein injections once tumors reached a volume of 150 – 200 mm3. Tumors and organs were collected, split and placed in either 10% formalin for histology or homogenized in 1× denaturing solution (Ambion, Austin, TX) for RNA isolation.

Tumor histologies and immunohistochemistries

Tumor tissues were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin using the Microm Tissue Embedding Center (Labequip, Ltd.; Markham, Ontario, Canada). Sections (5 μm) were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry stainings, sections were deparaffinized and hydrated and endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 in water for 10 min. Antigen retrieval was performed with 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min in a microwave oven followed by a 20-min cool down and thorough wash in tris-buffered saline with Tween20 (TTBS, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween20). Slides were incubated with Biocare Blocking Reagent (cat. no. BS966M with casein in the buffer, Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) for 10 min to block non-specific binding. Slides were incubated with various primary antibodies directed against: Ki67 (cat. no. M7249; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), Caspase-3 (cat. no. AF835; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), c-Met, Cdk4, and Bcl-2 (cat. nos. sc-162, sc-22, and sc-492 respectively; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), for 30 min at room temperature. Slides were washed in TTBS twice and then incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) at a 1:500 dilution for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, slides were incubated with anti-goat HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) for 30 min at room temperature followed by washing. Finally, slides were incubated with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (BioGenex Laboratories, San Ramon, CA) and color development was closely monitored under a microscope. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Cytokines and blood chemistries

Female Balb/c mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were injected i.v. in a lateral tail vein with 100 μg miRNA formulated with MaxSuppressor in vivo RNALancerII. As a positive control for cytokine induction, a group of animals was injected with 20 ug lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane using a Laboratory Animal Anesthesia System (VetEquip, Pleasanton, CA) and blood was collected via cardiac stick at set times points post injection into a serum separator tube for serum isolation or into an EDTA tube (Sarstedt, Newton, NC) for whole blood chemistry analysis. Serum cytokine levels were determined using a mouse fluorokine multi-analyte profiling kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and the Luminex 100 IS instrument. For blood chemistry analysis, whole blood was sent to the Comparative Pathology Laboratory at UC Davis.

Results

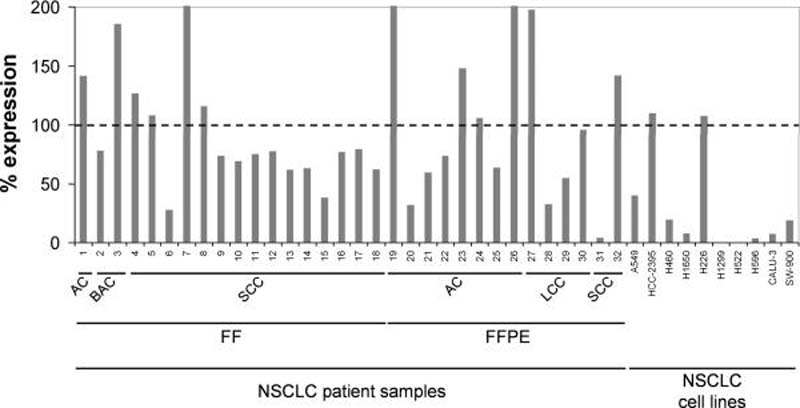

miR-34a is suppressed in human non-small cell lung cancer tissues

To assess expression levels of miR-34a in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), we have tested a cohort of 18 human tumor samples that were flash-frozen (FF) after biopsy, and a cohort of 14 tumor samples that were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded prior to RNA isolation (FFPE). The sample collection comprised the predominant histotypes of NSCLC, including 9 adenocarcinoma, 17 squamous cell carcinoma, 4 large cell carcinoma and 2 bronchioalveolar carcinoma (Supplementary Table 1). Expression levels in the tumor tissue were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and compared to levels in the corresponding normal adjacent tissues (NATs) (Fig. 1). Twenty of the thirty-two tumor samples (63%) showed reduced miR-34a expression with an average expression level that is 60% of the expression observed in the corresponding normal adjacent lung samples. Reduced miR-34a was observed in all histotypes of NSCLC in agreement with other reports showing downregulation of miR-34a in a broad range of tumor types including lung cancer (6, 7, 11). Tumor levels of miR-34a did not correlate with disease stage (Supplementary Table 1). Similar to tumor tissues, established NSCLC cell lines frequently showed a reduction in miR-34a levels (Fig. 1). The ones devoid of miR-34a expression carry mutations in the p53 gene (H1299, H522, H596, Calu-3, SW-900) (21, 22) in accord with previous data demonstrating that miR-34a is a transcriptional target of p53 (6, 13–16).

Figure 1. miR-34a expression in human non-small cell lung cancer.

qRT-PCR analysis of miR-34a using total RNA from 32 NSCLC tumor samples and their corresponding normal adjacent tissues (NAT), as well as total RNA from various NSCLC cell lines. Raw Ct values from lung tumors and NATs were normalized to a house-keeping miRNA (20) and expressed as % expression compared to levels in the respective NAT from the same patient (100%). Values derived from cell lines were compared to the expression value in Wi-38 normal lung fibroblasts (100%). FF, flash-frozen; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; AC, adenocarcinoma; BAC, bronchioalveolar carcinoma; LCC, large cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

To correlate miR-34a expression levels with the transcriptional activity of p53 in human tumors, we determined mRNA levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 and MDM2, both of which are transcriptionally induced by p53 and have previously been used as a measure for p53 activity (23–25). Thus, reduced p53 activity could be reflected by reduced levels of MDM2 and p21WAF1/CIP1 in the tumor tissue relative to NAT. However, other factors potentially contributing to the expression levels of these targets must be considered. The analysis was limited to 15 RNA samples generated from flash-frozen tissues, as RNA from FFPE samples does not exert RNA qualities that are sufficient to assess mRNA levels. Although no significant correlation was observed between p53 activity and miR-34a levels (R2p21/miR-34a=0.2094, R2MDM2/miR-34a=0.1495), all tumors with reduced miR-34a expression also showed reduced mRNA levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 and MDM2 (Supplementary Table 1). Similar results about p53 mutation status and miR-34a levels in NSCLC have been reported in (11). As anticipated, p53 mRNA levels did not correlate with those of its targets (R2p53/p21=0.0392, R2p53/MDM2=0.0692), in agreement with the observation that p53 levels are not indicative for its functional status (Supplementary Table 1) (25–27).

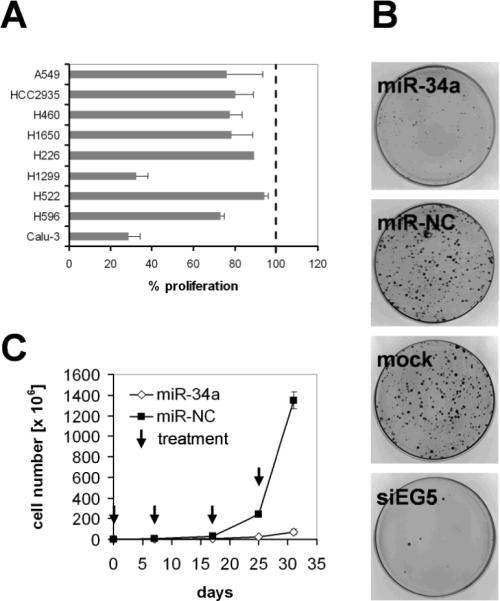

miR-34a inhibits growth of cultured lung cancer cells

The data suggest that suppression of miR-34a might be critical in acquiring a malignant phenotype and that reintroduction of miR-34a may interfere with the oncogenic properties of NSCLC cells. To test this possibility, we transiently transfected a panel of NSCLC cell lines with miR-34a and measured proliferation 72 hours thereafter. The human NSCLC cell lines chosen vary in histology and cancer genotype and therefore allow an evaluation of miR-34a induced effects in a genetically diverse set of NSCLC (22). As a control, cancer cells were transfected separately with a negative control miRNA (miR-NC) that contains a scrambled sequence and does not specifically target any human gene products (Ambion, Austin, TX). As an indication for successful transfection and extent of growth inhibition, cells were transfected with an siRNA directed against the spindle protein kinesin 11 (EG5; Supplementary Fig. S1A) (28). As shown in Fig. 2A, most cancer cell lines exhibited reduced cell growth in the presence of miR-34a. The degree of growth inhibition is similar to those of other lung cancer-directed therapies in transient cell assays (29). Cells transfected with miR-34a showed signs of stress as evidenced by a loss of the spindle-like shape followed by either rounding and detachment, or a large, flat senescence-like phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S2). Interestingly, the inhibitory effects of exogenous miR-34a were not limited to cell lines with reduced endogenous miR-34a expression and also affected cell lines with normal miR-34a expression levels (e.g. H226 cells, Fig. 1). Inhibition of cancer cell growth by miR-34a was also independent of p53 status (Fig. 2A). A colony formation assay using SW-900 cells carrying mutated p53 further demonstrates the ability of miR-34a to inhibit cell proliferation of NSCLC cells in the absence of functional p53 (Fig. 2B). Colony formation of cells transfected with miR-34a was merely 9% relative to cells transfected with miR-NC (100%) 32 days post transfection. SW-900 cells proliferate considerably slower than most other NSCLC cells and therefore we speculate that the miR-34a mimic is less rapidly subject to dilution due to ongoing cell divisions compared to fast-dividing cells which might explain the extended duration of miR-34a activity in SW-900 cells (30, 31). To study the long-term effects of miR-34a in rapidly dividing cells, we serially transfected miR-34a into H226 lung cancer cells, a cell line that moderately responded to miR-34a in transient transfection experiments. Cell counts were taken during the experiment and extrapolated to calculate population doublings and final cell numbers. miR-NC treated cells showed normal exponential growth (Fig. 2C). In contrast, miR-34a severely retarded H226 cancer cell proliferation. To assess whether the inhibitory effects of miR-34a were specific to cancer cells, we measured proliferation effects of miR-34a in non-malignant cell lines including normal Wi-38 lung fibroblasts. In contrast to cancer cells, transient transfection of miR-34a into non-malignant cell lines had no effect on their ability to proliferate (Supplementary Figure S1B). Similarly, a direct comparison of cellular viability of A549 lung cancer cells vs. normal BJ cells in response to increasing miR-34a concentrations indicated that normal cells are more refractory to miR-34a than cancer cells (Supplementary Figure S1C). In summary, the data suggest that miR-34a exerts an anti-replicative function in a broad range of lung cancer cells.

Figure 2. Inhibitory activity of miR-34a in cultured lung cancer cells.

(A) Transient effect of synthetic miR-34a. Cancer cell lines were transfected in triplicate with 30 nM miR-34a or miR-NC. Proliferation was assessed 3–7 d post transfection using Alamar Blue™ (Invitrogen). Percent (%) change in proliferation was plotted relative to proliferation of miR-NC transfected cells. Averages and standard deviations of three replicates are shown. (B) Colony formation assay using SW-900 lung cancer cells. Cells were transfected with synthetic miR-34a, miR-NC and siEG5 siRNA and seeded at 3000 cells per 100-mm dish. After 32 days, cells were stained with 2% crystal violet. Colonies containing >50 cells were counted. (C) Long-term effects of miR-34a. H226 cells were transfected in triplicate with miR-34a and miR-NC, seeded and propagated in regular growth medium. When the control cells reached confluence, cells were harvested, counted and transfected again with the respective miRNAs. The population doublings were calculated, and cell counts were extrapolated and plotted on a linear scale. Arrows represent transfection events. Average cell counts and standard deviations of three replicates are shown. Cell lines carrying mutated p53 include Calu-3, H596, H1299, H522 and SW-900 (21, 22). A549 and H460 carry wild-type p53 (21, 22).

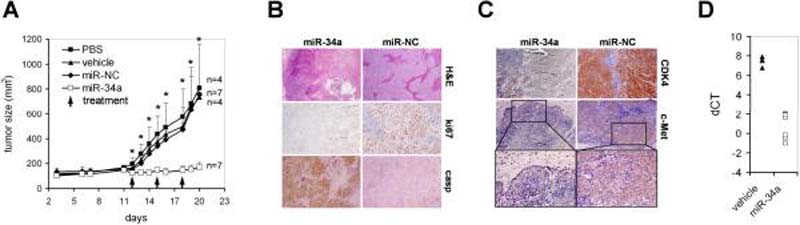

Intratumoral delivery of formulated miR-34a blocks lung tumor growth in mice

We next investigated whether administration of synthetic miR-34a could block lung tumor growth in the animal. Naked miRNA oligonucleotides are rapidly degraded in biofluids and therefore, we formulated the miRNA in a lipid-based delivery vehicle that is designed for systemic delivery of the oligonucleotide to various tissues (Materials and Methods). Since the range of an effective systemically administered miRNA dose and the rate of successful delivery to the tumor tissue were unknown, we first evaluated the miR-34a-induced effects by intratumoral injections using 100 μg oligo which corresponds to a relative concentration sufficient to induce growth inhibitory effects in cultured cancer cells. H460 NSCLC cells, a fast growing tumor xenograft that yields large tumors within 3 weeks post implantation, were grafted subcutaneously into the lower back of NOD/SCID mice and grown until palpable tumors have formed. On day 12 post xenograft implantation, a group of tumor-bearing mice received intratumoral injections of formulated miR-34a. Local injections were repeated on day 15 and 18 to maintain increased levels of miR-34a in the tumor tissue. As controls, a separate group of animals were treated intratumorally with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the vehicle only or vehicle formulated with miR-NC. As shown in Fig. 3A, tumors injected with formulated miR-NC were unffected and developed at a pace similar to those that received PBS or vehicle. In contrast, intratumoral injections of formulated miR-34a prevented the outgrowth of viable tumors. A histological analysis revealed that miR-34a-treated tumors contained large areas filled with cell debris (Fig. 3B). The few seemingly viable tumor cells that remained preferentially in the periphery of the tumor showed reduced expression of ki67 and an increase in caspase 3, indicating that miR-34a actively inhibits proliferation and stimulates the apoptotic cascade in H460 tumor cells. To better correlate the activity of miR-34a, we measured protein levels of endogenous CDK4 and c-Met, both of which are directly repressed by miR-34a (13). Tumors treated with miR-34a lacked the expression of CDK4 and c-Met relative to tumors that received miR-NC (Fig. 3C). Similarly, Bcl-2, another direct target of miR-34a (6), was repressed in tumors that received formulated miR-34a (Supplementary Fig. S3). While the down-regulation of CDK4, c-Met and Bcl-2 demonstrates the specific activity of miR-34a in H460 tumor cells, we assume that the regulation of other targets is necessary to explain the complete miR-34a phenotype. The expression of miR-34a targets inversely correlated with ~100-fold increased miR-34a levels in the tumor tissue relative to endogenous miR-34a levels in H460 tumor cells (Fig. 3D). The data suggest that local administration of formulated miR-34a induces a specific inhibitory effect in tumor cells with an accumulation of miR-34a and concurrent repression of its direct target genes.

Figure 3. Local delivery of formulated miR-34a inhibits lung tumor growth in mice.

(A) Effects of formulated miR-34a in H460 tumors by intratumoral injections are shown. Palpable subcutaneous H460 tumor xenografts were treated on days 12, 15 and 18 with each 100 μg formulated miR-34a or miR-NC. As controls, separate groups of tumor-bearing animals were injected with vehicle alone or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Caliper measurements were taken on days as indicated and averaged. Error bars indicate standard deviations. **, p values <0.05 (Student's t-test, 2-tailed, miR-34a and miR-NC); *, p values <0.01 (Student's t-test, 2-tailed, miR-34a and miR-NC). (B,C) Histologies and immunohistochemistry stainings directed against ki67, caspase 3, CDK4, c-Met of H460 tumors after sacrifice. Histologies at a 100-fold magnification and immunohistochemistry stainings at a ~300-fold magnification are shown. Insets show c-Met-specific stainings at a 400-fold magnification. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-34a in H460 tumors treated with formulated miR-34a or vehicle after sacrifice. Raw Ct values from lung tumors and NATs were normalized to a house-keeping miRNA (20) and expressed as dCT [log2].

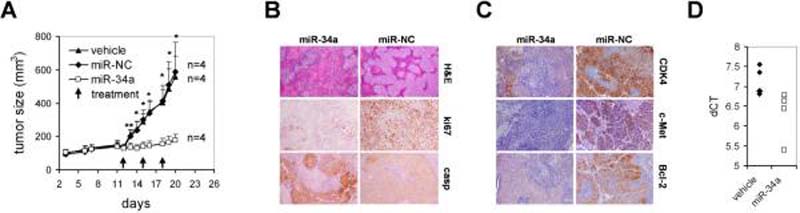

Systemic delivery of formulated miR-34a inhibits growth of established lung tumors in vivo

To evaluate miR-34a-dependent effects upon systemic delivery of the miRNA, we repeated the experimental framework using the H460 xenograft. Animals carrying palpable subcutaneous tumors were treated with formulated miR-34a, miR-NC or vehicle only. In contrast to the previous study, however, formulations were administered by intravenous tail vein injections. Each dose contained 100 μg formulated oligo which equals 5 mg/kg per mouse with an average weight of 20 g. Similar to intratumoral injection of miR-34a, repeated intravenous delivery of formulated miR-34a specifically blocked tumor growth (Fig. 4A). Tumor tissues from miR-34a-treated animals frequently showed areas with cell debris, reduced expression of ki67 and an increase in caspase 3 (Fig. 4B), in agreement with effects observed upon local delivery of miRNA. Systemic delivery of formulated miR-34a at 1 mg/kg also inhibited the growth of established A549 NSCLC xenografts, further demonstrating the anti-tumor activity of miR-34a (Supplementary Fig. S4A). The histologies and immunohistochemistry stainings of A549 tumors that received miR-34a resemble those of treated H460 tumors, suggesting that repeated administration of a miR-34a mimic inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in A549 lung tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Similar to local administration of miR-34a, the growth-inhibitory effects correlated with an accumulation of miR-34a in the tumor tissue and repression of c-Met, Bcl-2, as well as partial repression of CDK4 (Figs. 4C,D). However, the overall abundance of systemically delivered miR-34a in the tumor tissue was substantially less compared to locally delivered oligo and suggests that only minimal amounts of miR-34a are needed to elicit a therapeutic effect. Interestingly, the tumors with the greatest suppression of miR-34a targets were also the ones with the highest accumulation of miR-34a oligonucleotide.

Figure 4. Intravenous delivery of formulated miR-34a blocks growth of human lung tumors in mice.

(A) Mice carrying palpable subcutaneous H460 tumor xenografts were treated on days 12, 15 and 18 with lipid-formulated miR-34a, miR-NC, vehicle alone or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by intravenous tail vein injections. Each dose contained 100 μg of formulated oligo. Caliper measurements were taken on days as indicated and averaged. Error bars indicate standard deviations. **, p values <0.05 (Student's t-test, 2-tailed, miR-34a and miR-NC); *, p values <0.01 (Student's t-test, 2-tailed, miR-34a and miR-NC). (B,C) Histologies and immunohistochemistry stainings specific for ki67, caspase 3, CDK4, c-Met and Bcl-2 of H460 tumors after sacrifice. Histologies at a 100-fold magnification and immunohistochemistry stainings at a ~300-fold magnification are shown. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of miR-34a in H460 tumors treated with formulated miR-34a or vehicle after sacrifice. Raw Ct values from lung tumors and NATs were normalized to a house-keeping miRNA (20) and expressed as dCT [log2].

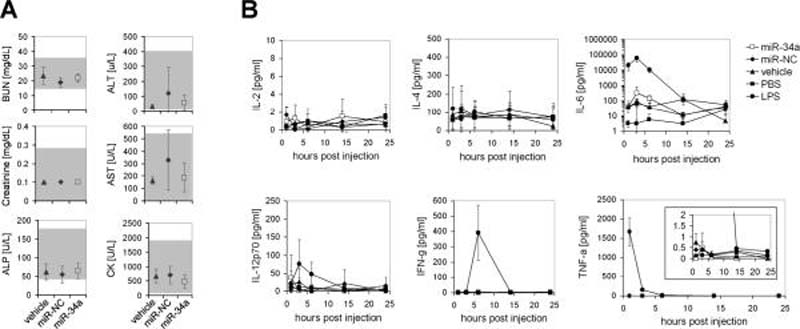

Systemic delivery of formulated miR-34a does not lead to elevated blood chemistries nor trigger an immune response

To assess the safety profile of systemically delivered miR-34a, we examined serum levels of ALT, AST, BUN, ALP, creatinine and creatine kinase from mice repeatedly treated with formulated miR-34a, miR-NC or vehicle alone. As shown in Fig. 5A, values of these blood chemistries, that would indicate toxicity in liver, kidney and heart, were within the normal range and suggest that miRNA treatment was well tolerated. To determine whether the anti-oncogenic effects of miR-34a are indeed a specific consequence of the miRNA and not the result of a non-specific induction of the immune system, we measured serum cytokine levels in immunocompetent Balb/c mice (Fig. 5B). An activation of the immune system has been reported previously to be induced by other oligonucleotide-containing formulations which might – at least in part – contribute to the effects of the therapeutic (32–35). Since a burst of cytokines usually occurs within just a few hours after administration of the stimulant, we evaluated cytokine levels 1–24 hours after intravenous administration of formulated miRNA (36–38). As a positive control, a group of mice was intravenously injected with a non-lethal dose of 1 mg/kg lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (39) which stimulated an induction of IL-6, TNF-α and IFN-γ (Fig. 5B). These LPS-treated mice also developed acute signs of illness, such as hunched posture, ruffled coat and labored movement, and fully recovered within 24 hrs post injection. In contrast, formulated miR-34a, miR-NC or the vehicle control failed to induce an immune response as evidenced by normal serum levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α (Fig. 5B), as well as normal levels of IL-1β and IL-5 (Supplementary Fig. S5) 1 through 24 hrs post intravenous injection. Similarly, mRNA levels of IFIT1, a gene induced by IFN-α, were solely elevated in response to LPS (Supplementary Fig. S6). Interleukin-6, a pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine, was slightly elevated 3 hrs after the injection of formulated miRNA; however, relative to the LPS control, this increase was mild and insufficient to reflect an actual immune response.

Figure 5. Blood chemistries and cytokine levels in response to systemic delivery of formulated miR-34a.

(A) Serum levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST) and creatine kinase (CK) of animals shown in Fig. 4A after sacrifice. Averages and standard deviations of all 4 animals are shown. The gray-shaded area indicates guideline ranges as reported by the Comparative Pathology Laboratory at UC Davis, CA. (B) Serum cytokine levels in immunocompetent Balb/c mice 1–24 hrs post intravenous injection of a single dose of formulated miR-34a, miR-NC, vehicle and PBS. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was used as a positive control for IL-6, IFN- γ and TNF-α induction. Averages and standard deviations of 3 animals per group are shown. IL-6 data are shown on a logarithmic scale.

Discussion

In summary, the data provide strong evidence for the safe and effective therapeutic delivery of a synthetic miRNA mimic. By reintroducing a tumor suppressor miRNA, miRNA replacement therapy seeks to restore a loss-of-function in cancer and to reactivate cellular pathways that drive a therapeutic response. As such, miRNA replacement therapy is distinct from other therapeutic approaches that are directed toward a gain-of-function, including kinase inhibitors, siRNAs and miRNA antagonists. We hypothesize that the synthetic miR-34a mimic acts like naturally occurring miR-34a and that it affects all mRNAs that are inherently regulated by endogenous miR-34a in normal cells for which the proper miR-34a-target interactions have evolved over a billion years. Of note, miR-34a inhibited tumor cells that are devoid of functional p53, suggesting that pathways downstream of miR-34a are sufficient to block cancer cell growth. miR-34a also inhibited tumor cells that showed normal levels of endogenous miR-34a, indicating that the therapeutic application of tumor suppressor miRNAs is not limited to replacement. This broad anti-oncogenic activity might be explained by the fact that miRNAs target multiple oncogenes and oncogenic pathways that cancer cells frequently become addicted to (2). Thus, the ability to affect multiple cancer pathways seems to be a key benefit of therapeutic miRNA mimics that act in accord with our current understanding of cancer as a “pathway disease” that can only be successfully treated when intervening with multiple cancer pathways (40–42). Other examples that support the concept of miRNA replacement therapy are provided by let-7, miR-16 and miR-26a, all of which can function as tumor suppressors and inhibit tumor growth in mouse models of cancer (18, 43, 44).

It is interesting to note that – although miRNAs affect a wide spectrum of genes – administration of formulated miR-34a was well tolerated. We speculate that uptake of miRNA mimics has no effect in normal cells because pathways regulated by the miRNA mimic are already activated by the endogenous miRNA in these cells. This may also suggest that targeted delivery to tumor tissues will not be necessary. The synthetic miRNA mimic is delivered systemically in a controllable formulation without the need of ectopic expression vectors and therefore, lacks many technical challenges associated with conventional gene therapy. Although future studies are needed to address long term efficacy and safety in higher species, our data on miR-34a highlight the utility of synthetic miRNA mimics and support the development of this new class of cancer therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

1

2

3

Acknowledgements

The authors thank P. Lebourgeois for pathological analyses, S. Beaudenon and M. Winkler for critical reading of the manuscript and J. Shelton for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (1R43CA134071).

Abbreviations

-

IFIT-1

interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1

IFN

interferon

IL

interleukin

miRNA

microRNA

NAT

normal adjacent tissue

TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare competing financial interests. J.F.W., L.R., K.K., M.O., D.B., and A.G.B. are employees of Mirna Therapeutics, Inc., which develops miRNA-based therapeutics. L.P. declares no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Oncomirs - microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:259–69. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrocca F, Lieberman J. Micromanipulating cancer: microRNA-based therapeutics? RNA Biol. 2009;6:335–40. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.3.9013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong AW, Nemunaitis J. Modulation of miRNA activity in human cancer: a new paradigm for cancer gene therapy? Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15:341–55. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bommer GT, Gerin I, Feng Y, et al. p53-mediated activation of miRNA34 candidate tumor-suppressor genes. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lodygin D, Tarasov V, Epanchintsev A, et al. Inactivation of miR-34a by aberrant CpG methylation in multiple types of cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2591–600. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tazawa H, Tsuchiya N, Izumiya M, Nakagama H. Tumor-suppressive miR-34a induces senescence-like growth arrest through modulation of the E2F pathway in human colon cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15472–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707351104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corney DC, Hwang CI, Matoso A, et al. Frequent Downregulation of miR-34 Family in Human Ovarian Cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 16:1119–28. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chim C, Wong K, Qi Y, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the miR-34a in hematological malignancies. Carcinogenesis. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallardo E, Navarro A, Vinolas N, et al. miR-34a as a prognostic marker of relapse in surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1903–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calin GA, Sevignani C, Dumitru CD, et al. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He L, He X, Lim LP, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007;447:1130–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:745–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raver-Shapira N, Marciano E, Meiri E, et al. Transcriptional activation of miR-34a contributes to p53-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:731–43. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarasov V, Jung P, Verdoodt B, et al. Differential regulation of microRNAs by p53 revealed by massively parallel sequencing: miR-34a is a p53 target that induces apoptosis and G1-arrest. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1586–93. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji Q, Hao X, Zhang M, et al. MicroRNA miR-34 inhibits human pancreatic cancer tumor-initiating cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esquela-Kerscher A, Trang P, Wiggins JF, et al. The let-7 microRNA reduces tumor growth in mouse models of lung cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:759–64. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ovcharenko D, Jarvis R, Hunicke-Smith S, Kelnar K, Brown D. High-throughput RNAi screening in vitro: from cell lines to primary cells. Rna. 2005;11:985–93. doi: 10.1261/rna.7288405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peltier HJ, Latham GJ. Normalization of microRNA expression levels in quantitative RT-PCR assays: identification of suitable reference RNA targets in normal and cancerous human solid tissues. Rna. 2008;14:844–52. doi: 10.1261/rna.939908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsudomi T, Steinberg SM, Nau MM, et al. p53 gene mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines and their correlation with the presence of ras mutations and clinical features. Oncogene. 1992;7:171–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer (COSMIC) Welcome Sanger Trust Institute; www.sanger.ac.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barak Y, Juven T, Haffner R, Oren M. mdm2 expression is induced by wild type p53 activity. Embo J. 1993;12:461–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.el-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, et al. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nenutil R, Smardova J, Pavlova S, et al. Discriminating functional and non-functional p53 in human tumours by p53 and MDM2 immunohistochemistry. J Pathol. 2005;207:251–9. doi: 10.1002/path.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soussi T, Beroud C. Assessing TP53 status in human tumours to evaluate clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:233–40. doi: 10.1038/35106009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–10. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weil D, Garcon L, Harper M, Dumenil D, Dautry F, Kress M. Targeting the kinesin Eg5 to monitor siRNA transfection in mammalian cells. Biotechniques. 2002;33:1244–8. doi: 10.2144/02336st01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janmaat ML, Kruyt FA, Rodriguez JA, Giaccone G. Response to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer cells: limited antiproliferative effects and absence of apoptosis associated with persistent activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase or Akt kinase pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2316–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartlett DW, Davis ME. Insights into the kinetics of siRNA-mediated gene silencing from live-cell and live-animal bioluminescent imaging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:322–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bartlett DW, Davis ME. Effect of siRNA nuclease stability on the in vitro and in vivo kinetics of siRNA-mediated gene silencing. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;97:909–21. doi: 10.1002/bit.21285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Judge AD, Bola G, Lee AC, MacLachlan I. Design of noninflammatory synthetic siRNA mediating potent gene silencing in vivo. Mol Ther. 2006;13:494–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Judge AD, Sood V, Shaw JR, Fang D, McClintock K, MacLachlan I. Sequence-dependent stimulation of the mammalian innate immune response by synthetic siRNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:457–62. doi: 10.1038/nbt1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, et al. Sequence- and target-independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3. Nature. 2008;452:591–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma Z, Li J, He F, Wilson A, Pitt B, Li S. Cationic lipids enhance siRNA-mediated interferon response in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:755–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agelaki S, Tsatsanis C, Gravanis A, Margioris AN. Corticotropin-releasing hormone augments proinflammatory cytokine production from macrophages in vitro and in lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxin shock in mice. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6068–74. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6068-6074.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edmiston KH, Gangopadhyay A, Shoji Y, Nachman AP, Thomas P, Jessup JM. In vivo induction of murine cytokine production by carcinoembryonic antigen. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4432–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pickering AK, Osorio M, Lee GM, Grippe VK, Bray M, Merkel TJ. Cytokine response to infection with Bacillus anthracis spores. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6382–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6382-6389.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang B, Trump RP, Shen Y, et al. RU486 did not exacerbate cytokine release in mice challenged with LPS nor in db/db mice. BMC Pharmacol. 2008;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Check Hayden E. Cancer complexity slows quest for cure. Nature. 2008;455:148. doi: 10.1038/455148a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kota J, Chivukula RR, O'Donnell KA, et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137:1005–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeshita F, Patrawala L, Osaki M, et al. Systemic Delivery of Synthetic MicroRNA-16 Inhibits the Growth of Metastatic Prostate Tumors via Downregulation of Multiple Cell-cycle Genes. Mol Ther. 2009 doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1

2

3